એક સાઈકોથેરૅપિસ્ટ તરીકે, હું ક્યારેય ખતનાની ભલામણ નહિં કરું

(This article was first published in English on December 10, 2016. Read the English version here.) લેખક : અનામી ઉંમર : 36 વર્ષ દેશ : ભારત હું એક માનસિક આરોગ્ય ચિકિત્સક છું અને છેલ્લા 16 વર્ષોથી હું તેનું કાઉન્સેલિંગ અને થેરાપી આપી રહી છું. મારા ઘરનાં લોકો મારી એક કઝિનની સેરિમનિ વિષે બોલતા હતા ત્યારે અનાયાસે જ મને ‘ખતના’(ટાઈપ 1 એફ.જી.એમ.) વિષે જાણવા મળ્યું. હું વધારે માહિતી મેળવવા માંગતી હતી. મને સમજાયું નહિં કે હું પણ તે પ્રક્રિયા હેઠળથી પસાર થઈ હતી. મને વધારે કંઈ યાદ નથી, બસ આટલું કે મને બળતરા થતી હતી અને ત્યારબાદ મારી માં અને નાની દ્વારા તપાસવામાં આવી રહી હતી. તે એક હરામની બોટી હતી જેને મારા શરીરમાંથી કાઢી નાખવામાં આવી હોવાથી મારે તે વિષે ક્યારેય વાત કરવી જોઈએ નહિં તેવા વાતાવરણમાં હું મોટી થઈ. મને કહેવામાં આવ્યું હતુ કે હવે તુ શુદ્ધ થઈ ગઈ છે. હું મોટી થઈ તેમ મેં સાઈકૉલોજીનો અભ્યાસ કર્યો, હું એફ.જી.એમ. વિષેનો એક આર્ટિકલ વાંચતી હતી ત્યારે અચાનક જ મને સમજાય ગયું કે તે દિવસે મારી સાથે શું બન્યું હતુ. મને ધક્કો લાગ્યો પરંતુ, તેને સ્વીકારવા સિવાય મારી પાસે કોઈ વિકલ્પ નહોતો કારણ કે જે કંઈ બન્યું તેની કોઈ અસર સમજાઈ નહોતી – મારા પ્રગતિશિલ માં-બાપને પણ નહિં. મારૂં જીવન અન્ય છોકરીઓની જેમ આગળ વધવા લાગ્યું. મારૂં લગ્ન જીવન, ખાસ કરીને સેક્સ પર તેની કોઈ અસર થઈ નહિં. મારૂં સેક્સ્યુઅલ જીવન અને ઑર્ગેઝમ્સ પણ સંતોષપૂર્ણ હતા અને મેં મહેસુસ કર્યું કે મારા પર ખતનાનીં કોઈ મોટી અસર થઈ નહોતી અથવા સાત વર્ષની ઉંમરે હું જે પ્રક્રિયા હેઠળથી પસાર થઈ તેનાં આઘાતનો સામનો કરવા મેં એ બાબતને એકદમ દબાવી દીધી હતી. જો કે, મને યાદ છે કે બાળકનાં જન્મ સમયે મારે એપિસિઓટોમી પ્રક્રિયા કરાવવી પડી હતી. UNFPA દ્વારા કરવામાં આવેલ એક સ્ટડી અનુસાર, એક સામાન્ય બૈરીની સરખામણીએ જે બૈરી પર જેનિટલ કટિંગની પ્રક્રિયા કરવામાં આવી હોય તેને સિઝેઅરિયન સેક્શન અને એપિસિઓટોમી ની વધારે જરૂર પડે છે અને બાળકનાં જન્મ પછી વધારે સમય હૉસ્પિટલમાં રહેવું પડે છે. આ વર્ષની શરૂઆતમાં પીઅર સુપરવિઝનમાં, મારી સાથે જે કંઈ બન્યું તેની પ્રક્રિયાને મેં ધીરે-ધીરે સમજી અને તેને જીવનનાં એક ભાગ રૂપે લીધી. મને એ બાબત પાછળથી સમજાઈ કે એફ.જી.એમ. ની અસરો થાય છે. હકીકતમાં તે આત્માને જખમો આપે છે અને આપણને આશ્ચર્ય થાય કે શું આ પ્રક્રિયા કરવી ખરેખર જરૂરી છે. ખતના પ્રક્રિયા લાંબા સમય સુધી માનસિક તણાવ આપી શકે છે. કુટુંબનાં સભ્યો દ્વારા ભરોસો તોડવાની લાગણીને કારણે તે બચ્ચાઓનાં વર્તનમાં ગરબડ પેદા કરી શકે છે. મોટી છોકરીઓ પણ બેચેની અને તણાવ મહેસુસ કરી શકે છે. જે આવી બધી બાબતો સમજે છે, તેવા એક મનોચિકિત્સક તરીકે શું હું ખતનાની ભલામણ કરીશ? ના, હું ભલામણ નહિં કરું કારણ કે, મને લાગે છે કે તેનો મુખ્ય હેતુ બૈરીઓની સેક્સ્યુઆલિટી પર નિયંત્રણ લાવવાનો છે. હું તેની વ્યાખ્યા લિંગ આધારીત હિંસા રૂપે કરીશ.

As a psychotherapist, I would not recommend khatna

(This article was later published in Gujarati. Read the Gujarati version here.) by Anonymous Age: 36 Country: India I am a mental health professional and have been practicing counseling and therapy since 16 years. I learned about the practice of ‘khatna’ (Type I FGM) by chance, as my family spoke about the ceremony for a cousin of mine. I wanted to know more. I did not realize that I too had undergone it. I have no memories save a snapshot of me feeling a burning sensation and then being examined by my mom and grandmom. I grew up learning never to talk about this subject, as this was the haram boti that was removed from my body. I was told I was now pure. As I grew older and studied psychology, I came across an article that spoke about FGM, and suddenly I understood what had happened to me on that day. I was shaken but left with no choice but to accept it, as no one understood the impact of what had happened – not even my progressive parents. My life proceeded from then on no differently from that of other girls. My marital life, especially the sex, was unaffected. I was able to have a satisfactory sexual life and also orgasms, and largely I felt I was not affected by the khatna. Either that or I had repressed it so as to cope with the trauma that I may have undergone at the age of seven. I remember at childbirth, however, I had to undergo an episiotomy. According to a study cited by the UNFPA, women who had undergone genital cutting faced a greater risk of needing a Caesarean section, an episiotomy, and an extended hospital stay after childbirth, compared with uncut women. In peer supervision earlier this year, I processed what happened to me and dealt with it as a part of my life. I recognize in hindsight that there are effects of FGM. It scars the soul and you wonder if it is even required to be done. The procedure of khatna may cause lasting psychological stress. Among children, it could trigger disturbances in behaviour, often because of betrayal of trust by loved ones. Adult women could also develop anxiety and depression. As a mental health professional who understands all this, would I recommend khatna? No, I would not, as I find that at its core, it is a measure to control women’s sexuality. I would term it as intentional gender-based violence.

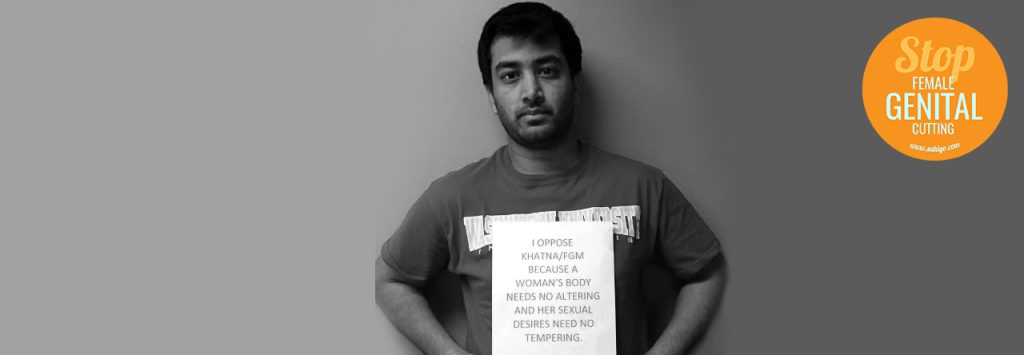

Why the khatna conversation needs men’s voices too

(First published on June 7, 2016) by Ammar Karimjee Age: 24 Country: Pakistan I found out when I was 19. I’d just heard about the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in an Anthropology class, and had dismissed it as something that simply happens in rural African villages. After class, I’d expressed disgust to a friend about it, something along the lines of “Can you believe people still do things like this?” The friend was a fellow member of the Dawoodi Bohra community, who in this moment realized I must not have known. After she spoke to me about it, I remained in disbelief. I was sure she must be wrong. I reached out to my mom and sister, and after a few in-depth conversations with them, it settled over me. A mix of emotions – anger, frustration, humiliation – all overcame me simultaneously. I didn’t do anything at first, I just needed some time to let it all sink in. After I’d had time to process, I realized I needed to do something. At first, most of my involvement in my personal anti-FGM campaign came through conversations with people I knew, primarily men. Even in this initial stage, I realized how essential it would be to effectively engage men as part of this movement. Over time, I became involved in a few more formal networks that were also working on this issue, and through these, I’ve had the chance to speak at the United Nations on this issue as well as be a small part of the This American Life podcast a few weeks ago. It’s been an amazing journey to be a part of. Below, I’ve shared some of the major learnings/thoughts I’ve developed over the last 5 years. I hope it can serve as a way for some of you to help think through this topic. If you have questions, there are a ton of us here to help guide you to the answers. If you’d simply like to talk further about this, please do not hesitate to reach out. You can always contact Sahiyo at info@sahiyo.com to become connected to others working on ending FGM. Some men don’t want to even engage in the conversation about FGM. Part of this is because they dismiss it as an unimportant issue at face value, but I believe a larger part of this may have to do with the discomfort that comes with talking about the female body and the lack of knowledge that it results in. As men, we do not intuitively understand the female body and the biological processes that occur within it. Of course, we never will be able to truly know what being a woman feels like, but by gaining an understanding of how their bodies work, we can begin to have an idea. Naturally, we compare things that happen with a woman to its closest direct male counterpart. As such, we associate FGM, or circumcision as many people chose to incorrectly refer to it as, as the equivalent of male circumcision. This is a dangerous fallacy for men to turn to in their justification. The function of the male penis and a woman’s clitoris are not identical – not even close. Further, the benefits that come from male circumcision are simply not present in FGM. Please, please, please, do your research and understand the impact of this practice. It is terribly important for men to be aware of women’s bodies – not just specifically to be able to understand FGM, but for so many other reasons, health and otherwise. For the men who were willing to talk about it, one constant held true – they had never talked about it before. Creating a space to have these conversations became an important part of the larger effort to engage men. But the snowball effect definitely holds true. Individual conversations I was leading turned to group conversations I was just a part of. Soon after, conversations started happening without me there at all. Awareness of FGM in the Bohra community has increased exponentially since I started speaking about this issue, especially in the last few months. However, the conversations happening are still dominated by women. It is of course amazing that so many women have started sharing their stories and thoughts. But we still live in a patriarchal context. Religious leaders are still men. Decision-makers in families are still largely men. We – the men – MUST start caring. We don’t have the option to be silent or ambivalent anymore. We can not keep pretending that it isn’t our problem. These are our friends, our daughters, our sisters, our mothers, and our wives. Read their stories. Understand what FGM is and how it affects them. Once you do, you’ll be as angry as I am. You won’t want it ever happening to anyone you’re close to. We can’t undo what has already happened to hundreds of thousands in our community – but we CAN prevent it from happening from this day forward. To men everywhere – Start reading. Start talking. STOP FGM.

I was cut, but today I am proud to be standing up for myself

(First published on March 16, 2016) Name: Alifya Sulemanji Age: 42 Country: United States I, Alifya Sulemanji went through the atrocity of Female Genital Mutilation. It’s been 35 years but I haven’t forgotten that day of my life even today. One morning my mom told me we were going to visit my aunt who lives in Bhendi Bazaar in Mumbai, where many of the Bohras live. In the midst of the day my mom, aunt, and her daughter (my cousin) told me that they were taking me somewhere to remove a worm from me. I was barely 7 years old then and didn’t know what they were really talking about. I blindly followed them. We entered some building and went up the stairs and got into this lady’s house. I had no clue what was going on. They told me to lay down on the floor assuring me that it was so they could take out a worm from my body and it was going to be very simple. My mom told me she was so devastated, she decided to leave the room and wait outside. They took off my underpants and I saw the lady remove a brand new sharp Topaz blade from the wrapper. They caught my legs and hands so I couldn’t move. I was watching them innocently, not knowing what’s going on. In a few moments, I was screaming in pain. My private part was in terrible shooting pain and I was crying. They told me to be quiet and I would be fine. The lady dabbed some black power on my cut area to stop me bleeding. After the procedure was done I was told to keep quiet; it was a secret not to be told to anyone. But today I am sharing my experience with the world. My life has been different since then. Not that I am not happy and successful, but it has left some everlasting effects on me. I have two lovely daughters. Most of the time I am paranoid about their safety and protection. I keep getting bad thoughts that someone might harm them. People have judged me as an overprotective and possessive mom, but they don’t know where it’s coming from. My husband told me that sometimes at night when we are sleeping, he hears me cry in my sleep. Many times I get nightmares about my daughters being in trouble and I wake up screaming. I have unknown fears and phobias. I have seen a psychologist regarding this. Today, I am happy and proud for standing up for myself.

We must realise that there is an alternative to khatna

by Insia Jaliwala Age: 18 Country: India The experience of khatna, not only the actual act but the implications of the practice, was a gradual revelation for me. In the vague haze of childhood memories, that particular day stands out. I must have been around 6 or 7 years old. My parents told me I could miss school that day and were taking me out, I was obviously very ecstatic. I was taken to a ‘lady doctor’; a gynecologist who applied a red serum on my hand with a cotton bud and asked if it burned. It did. She then proceeded to do the same to my genitalia. I remember the moment when she told me to remove my pants and lie down on the bed. “It’ll be over in a minute,” she said while holding a scalpel in her hand. There wasn’t much bleeding and I don’t even remember the pain. What I do remember is an inhibiting confusion and fear. That day isn’t registered in my memory as a traumatic event, but a day I associate with a sense of loss. That day an important part of my womanhood was snatched away from me. That day my body was mutilated without my consent. The reality of the twisted practice struck me only a few years ago when I got into a conversation with my elder sister who told me about her experience, which was much worse and painful. After, I started to explore the subject more. I read about female circumcision and came across horrifying stories from Africa. I stumbled into many stories of khatna told by the women around me. I had started to understand the terrifying implications of the practice which differed from person to person and the physical and mental trauma some of my own sisters and close friends had to go through, and are still going through. I also came across many justifications for the practice, some from my family elders which went along the lines of, “This is done to curb a girl’s sexual desire so that she can put her mind to other things”, among many others. All of this left me with an overwhelming sense of betrayal. My family, my community, had failed me. As I dwelled into it more, I realized that this act of oppression had (as with any other social issue or phenomenon) multiple dimensions and was woven in a convoluted fabric of culture, custom, and tradition. Earlier this year, as a film project for college, I decided to make a documentary on Khatna. During my research for the film, I came across Sahiyo and was amazed by the fact that so many women were willing to share their stories on this platform. My initial thought when I decided to make the film was that no woman would want to talk about this on camera. To my surprise and glee, many women around me agreed to be a part of it. There are hundreds of women (and men) out there who want this barbaric practice to stop. There needs to be a discussion about this on a communal level and people of the community need to realise that they have an alternative, they can choose not to impose this upon their young ones.

Proud to present: ‘A Small Nick or Cut, they say…’

A letter on khatna by a young Bohra man

by Anonymous Age: 28 Country: United States Hello All, Firstly, I would like to start by telling you how ashamed I feel of being so ignorant about the issue of female khatna and how honored I am to be a part of a family whose women are spearheading the fight against FGM. I am from an Islamic Dawoodi Bohra family that comprises mainly of women. I have six beautiful sisters. They have all undergone khafd (khatna). Back then, there was no awareness and there was tons of social pressure. Everything was done quietly and no one spoke about it. At least in my community, it was a given that a girl child had to have her khatna done. Not doing it would be condemned. Women who have gone through FGM have started talking about their experiences. Openly speaking about this issue has done great good for the community as it has helped build awareness and made folks like me, who were ignorant about it, read and learn more about it. I salute the women who have been bold to talk about this. Thank you! Listening to these experiences makes me really sad. Sad because this has been going on for so long and this practice has absolutely no foundation. It makes me sad that educated people never questioned it and were so socially engrossed that they just did what they were told to do. It makes me sad because it just proves how sexist the world is (which I do not want to believe). It saddens me because parents are still putting their daughter through this. For my religious friends: the Quran does not even mention khatna. So please do not put a religious aspect to this practice. This practice only has side effects. For those who are not aware – please please read here. More importantly – it is her body, please respect it. This issue is important and it must be dealt with. It needs support from each and every member of the community including the men.

I was stripped of many things the day I was cut

(First published on January 23, 2016) by Mariya Ali Age: 32 Country: United Kingdom I have very few memories of my childhood, but one memory in particular stands out and haunts me to this day. Unfortunately, it’s a vivid, painful memory and fills me with anger when I recall it. I was five years old when my mother and aunt took my cousin and I on an “excursion”. I remember sitting in a car and approaching an unfamiliar block of apartments. I was confused; I didn’t know where I was and what I was doing there. Despite my seemingly endless young imagination, I could never have anticipated what happened to me next. I walked into a small apartment with a cramped living room at the end of a very short corridor. There was a dampness in the air and a slight smell from the poor ventilation. I approached the living room and sat on the floor. It was a warm day and I watched the net curtains of the large window slowly move with the breeze. I had been greeted by an old lady, whose face I can’t remember. I didn’t recognise her and was confused as to why I was currently in her apartment. I watched as she walked out of the room. I peered inquisitively into the kitchen and caught a glimpse of her heating a knife on the stove. I was always told to stay away from sharp knives at that age. Knives were dangerous. I could hurt myself. I remember the open flame on the stove and seeing the silver of the metal and the black handle of the knife while I watched her quickly hold it over the naked flame. She approached the living room with the knife in her hand, trying to conceal it behind her. She approached me. My mother asked me to remove my underwear. I remember saying no; I didn’t want a strange woman to see me without my underwear on. My mother assured me it would be okay; I trusted her and did as she asked. The old lady told me that she wanted to check something in my private area and asked me to open my legs. I was so young that I wasn’t scared at that time. I was confused, but not scared. I was innocently oblivious to how invasive and inappropriate this situation was and so I obediently did as I was told. I remember a sharp pain. An agonising pain. A pain that I can still vividly remember today. So intense that I still have a lump in my throat when I recall that moment. I instantly started sobbing, from pain, shock, confusion and fear. My next memory is that of blood. More blood than I had ever seen, suddenly gushing out from my most intimate area. I still didn’t comprehend what had just happened to me. I had believed that aunty when she had told me that she was checking something. I was young and naive enough to believe that people don’t lie and this was my first encounter when I realised that, unfortunately, the world doesn’t work like that. In so many ways I was stripped of many things on that day. My rosy outlook on life, my childhood innocence, my right to dictate what happens to my body and my faith in my mother not harming me. I continued to cry, the pain was excruciating and the sight of the blood traumatised me. I was given a sweet and comforted by my mother. The events after that are still hazy and my next clear memory is that of being back in the car and staring through teary eyes at the apartment building disappear as we drove away. Over the years I repressed this memory. There was no need to recall it. It was never spoken about and I still remained unaware of what transpired that day. A decade later, I was amongst some of my female friends. The topic of Female Genital Mutilation came up, or as I was to discover that day, “khatna”, a Bohra ritual performed on young girls. Hearing their recollections of what had happened to them, I finally realised that this is what had happened to me that day. I was mutilated. Thankfully for me, I had a lucky escape. The unskilled, uneducated woman who barbarically cut me did not cause me too much physical damage. Emotionally and mentally, there are many repercussions. I have a deep phobia of blood and a simmering resentment that my mother chose for this to happen to me. Although my mother believed that she was acting in my best interest, I struggle to come to terms with the fact that I was so barbarically violated. It may have been just a pinch of skin, but it was a part of me, a part of my femininity and a part of my womanhood.

They told me they would call a ‘bhoot’ if I didn’t stop screaming

(First published on February 26, 2016) by Fatema Kabira Age: 19 Country: India Seven years old. I was seven years old when they forced me to have a part of my femininity cut off. I don’t remember much from my childhood. My memories are very vague. Yet, despite my poor memory, I clearly remember the day I was circumcised. That day is a vivid memory. My grandmother and mom told me I was going for a sitabi (a celebration for women and girls). I used to love sitabis when I was a kid. So, I got really excited and eagerly awaited going to the sitabi. I even insisted to my mom that I wear my new clothes and topi. After dressing up in my favourite clothes, I left with my grandmother and mom to go to the sitabi. We didn’t end up attending any sitabi and instead we went to a place that was unfamiliar to me. It was an old looking building. The steps were covered with dust and were broken. I was confused why we were there. We went inside somebody’s house and were greeted by a middle-aged woman whom I failed to recognize. I asked my mom what was going on, but she ignored me. The house was small with only one room, kitchen, and a storage unit attached to the ceiling. The one room was dim and gloomy and gave out an eerie feeling. The Aunty chatted with us for a while and then went inside another room to bring something back. When she came out she had a blade and 2 or 3 other items in her hands (I can’t recall what they were). She came and sat in front of me. My mind went blank. I thought, ‘Blade? For what?’ My grandmother then asked me to remove my pants. Innocently, I told them I did not want to use their washroom. My 7-year-old brain could not comprehend any other reason why my grandmother would ask me to remove my pants. And that too in front of an unknown woman, since my grandmother knows how shy I was even in front of my own mother. But I obliged my grandmother’s request. They made me lie down and held my hands firmly to the ground. The next thing I remember is the sight of the silver blade and a sharp agonizing pain in my most intimate area. I screamed in terror. What did they do? The Aunty told me to keep quiet or she will call the “bhoot” (ghost) that stayed in her storage unit. I didn’t oblige this time. I screamed and yelled and tried to free myself. It was all in vain. They did what they wanted to do. It was all over. I cried all the way home. It hurt every time I urinated. The sight of the blood made me sick. I was hurt and angry and confronted my mother about this. She told me she was under religious obligation and she did what thought was the right thing to do at that time. Fortunately, I didn’t face any medical repercussions due to the unhygienic and brutal way in which I was circumcised. But it has left a psychological impact on me. I feel disgusted, ashamed, and angry at what has been done to me. There is no reason that justifies this barbaric practice. There is no reason that justifies taking away women’s inherent physical rights and ability to experience pleasure. Young girls are scarred for life and this needs to be stopped.

I am grateful I was able to talk to a therapist about my khatna

(First published on January 6, 2016) by Anonymous Age: 30 Country: United States I was not more than seven years old when I recall going into a medical complex on a quiet Sunday afternoon accompanied by my mother and our family friend. My mother told me it was time for my “khatna” or circumcision. She explained it as a rite of passage, something all the little girls in our Dawoodi Bohra community had to do. I remember feeling scared but I didn’t know exactly why. I just had a feeling something terrible was about to happen to me as our friend unlocked the building with her keys and we continued into her desolate practice. We went into one of the brightly colored rooms where alphabet wallpaper boarded me in. I started crying before it even happened while she crooned, “all I’m going to do is remove a liiiitle piece of skin.” Totally exposed, I was asked to relax and read the wallpapered alphabet backward. My mother helped hold me still while I was flat on my back and in hysterics. The snip which took maybe half a second was followed by a sharp-shooting pain that seemed to last in that moment, for eternity. I bled for three days and then it was over. It wasn’t until I was nineteen, the end of my freshman year in college that I stumbled upon an article from one of my classes, describing the experience of a woman who had been a victim of FGM, or female genital mutilation. After reading the article once, I was immediately reminded of that Sunday afternoon twelve years prior. There was no way the same thing could have been done to me. My seven-year-old perspective of a little piece of skin being removed was analogous to that of a piece of skin from the top layer of the palm of a hand. My cousin used to stick a needle through that top layer and tell me it was magic that the needle was sticking there. She eventually revealed her secret and showed me the protective top layer that separated her hand from the skin. I guess like that layer, I always figured it would grow back. Still, the feeling of uncertainty drove me to call a couple of peers and academics in my community to ask whether our “khatna” was in fact, a partial removal of my clitoris. Their answer confirmed the worst of my fears. My next concern of “how much?” tormented me, and after a frantic visit to the school nurse, I got my answer: “There’s only a remnant left,” said the nurse practitioner who examined me. *** I don’t believe my discovery was adequately addressed the first time as the rest of my college experience was consumed by bouts of grief, rage, frustration, insecurity, and depression. My feelings only grew stronger as I got older and had more encounters with the opposite sex. My overcompensating, defensive attitude permeated all aspects of my life—friends, family, work, and academics. It wasn’t until my mid-20s when I shared with my gynecologist during a routine visit what happened to me, that I was given three names of specialized therapists in the area with whom I could speak about my concerns. My insurance provider at the time would not cover therapy. Fortunately, one of three therapists agreed to see me for a discounted out-of-pocket fee because she was interested in my case. To this day, I am so grateful for the opportunity I had to talk through what happened to me in a safe space as such resources and treatment were unavailable to me at home or in my community. I learned it was ok to talk about sex, explore my sexuality, and sexual feelings. I was even prescribed homework to assist me in doing so. At the time of the therapy, I had been sexually active and my partner, who was incredibly supportive, was also invited to participate in one of my sessions. When growing up, I never thought I would have sex before marriage. The idea behind the circumcision was to curb any sexual appetite I might have. Ironically, once I learned this had happened, I wanted nothing more than to have sex to see what my capabilities were. While I was incredibly nervous and insecure about having sex, I was more open to losing my virginity in the context of a serious relationship, which is how it happened for me. One of my main insecurities about sex was that I felt like I was driving without the headlights on. Often times, I didn’t know where to go or how to guide my driver. I felt like a failure. To this day, I still have not experienced orgasm. While sex is enjoyable for me and I could describe what I can achieve as a “mini-climax”, I am bothered by the fact that I may never get to experience this wonderful part of life. While it’s no secret many women who have not been “circumcised” struggle with the same issues, a part of me will always wonder if that would have been true for me had this not happened. I will never know.