Healing from Khatna with EMDR

By: Sunera Sadicali Trigger warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of female genital cutting (FGC). Khatna (or FGC) is much more than a physical wound. It has stayed quiet in my mind. I was not conscious of the impact of FGC on me and had dismissed it with all kinds of justifications. My therapist uses eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) to help me process the trauma, and we decided to address this episode of my life that “I cared little about.” EMDR is an evidence-based trauma therapy that uses bilateral brain stimulation to process traumatic experiences. In a simple way, it helps the person to make sense of and resignify the trauma, resulting in a more adaptive and coherent narrative of the past experience and their life. In a nutshell, this is how it is performed: 1. First, the therapist helps the patient identify the traumatic memory they want to heal from. 2. Through sounds, taps, or eye movements, the therapist guides the patient through processing the memory as the patient focuses on it. 3. The therapist and patient repeatedly do this until the memory is no longer disturbing. With EMDR I go back in time; my therapist asks me, “Where are you? What do you feel in your body?” I visualize the waiting room, the sliding doors, and my sister on my left side. She is small, and she is as scared as I am because nobody explained to us what was going to happen. Our cousin was taken, and suddenly we heard a loud scream. “I feel in my body the fear of the pain, of the unknown. I feel fear in my whole body. I know that whatever is happening there, I am the next one.” My eye movement continues from one side to another. I feel safe with my therapist, I flow, I am in my body. Next, I am laid down on that gurney. The room is half dark, my aunt is on my right side, and my mother is on my left. In front of me, there is a woman, a doctor with a white coat. “I feel the fear in my body again.” They grab me from my legs, I am in a lithotomy position, and they hold me down with force. I can’t see my pelvis, I can’t see what is going to happen, nobody is telling me. There is no explanation, no asking consent, no describing the purpose of the act. “I feel the pressure of my legs, and suddenly, a sharp pain like an electric shock coming from my genitals.” I cry all along in fear and pain. She tells me it is a little worm that needs to be cut. That’s all. My eye movement continues from one side to another. “I go back to the pain, to the fear.” There is a silence between the act and the worm. There is a silence that has never ceased to exist, nobody told you before the worm, nor after the pain. There is silence between me and my sisters, silence between my mother, and between my aunty and myself. We never talked about the act itself. How it was done. “Why?” I believed it was not a big deal. Não era para tanto. “You don’t have to complain because it was a very small cut, look how they do it to African women.” Until today, I had not understood the seriousness of what had happened to me. The living body sensations it had caused. How it was carried out, and executed as the norm. The norm is that you are not allowed to complain. Entering my body through EMDR, feeling the moment of Khatna again, before and after, allowed me to understand the beliefs that were generated from this act. The belief is that whatever happened to me is “not so important,” because it was not seen as important then. Traumatic experiences generate wrongful beliefs about ourselves. The belief that you have no right to complain. That it was for your own good, you were lucky enough that a doctor performed it, that you felt little pain. These are ways to cover up violence. Silence, lies, force, violence, continuing to perpetuate and defend a crime. Since it was implemented, EMDR has been recognized as evidence-based psychotherapy by the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) and in 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the use of EMDR in adults and children with post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD). The brain has the intrinsic capacity to heal itself from disturbing events and experiences, by forming different pathways. If this is not achieved, for example, because of the lack of emotional support in childhood to help integrate these experiences, or validation, reparation, or acknowledgment from the external world, parents, or attachment figures, the traumatic memories will be blocked and retained as an implicit memory…buried inside the mind without having permission to come out. It then becomes a wound that keeps inflicting damage, in our unconsciousness. This creates unhealthy beliefs about ourselves, especially as a child. Children need to protect their relationship with their parents, and their family, to keep the attachment and love alive; they will unconsciously excuse their parents, and if it’s needed allow wrong beliefs about themselves to justify what has happened to them. EMDR, with its bilateral stimulation, helps me to connect and restore the balance in the systems that process traumatic experiences. It is a bottom-up therapy that installs positive information on various levels: the body, emotions, sensations, and belief systems. I am currently receiving EMDR therapy, and I was recommended this modality — along with psychotherapy — to promote healing in general, especially from FGC as it happened in childhood and is related to sexuality and patriarchal mandates. EMDR works at a body level, and works on the memories of the body sensations, allowing the non-adaptive beliefs to emerge and to be replaced by new more positive, and resilient ones. Related links: Learn more about Asian Women’s

Sexual pleasure after female genital cutting

By Derrick Simiyu “Female genital cutting is practiced to control women’s sexuality.” This statement was one of the first things I learned as I read through materials on Sahiyo’s website when I began my internship, as an Events and Programs Intern. This inspired me to think about how harmful female genital cutting or FGC is, and how it is still being practiced even with the advancement in education and knowledge. I find it concerning how patriarchy can restrain a woman’s sexual desires, rather than celebrate them. I decided to do some research about FGC and the outcomes of the practice, particularly in relation to sexual pleasure, as well as how survivors can heal sexual traumas as a result of FGC. How does FGC affect sexuality? A study by the National Library of Medicine explores this complexity in women, and how FGC may or may not affect their pleasure and orgasm.Every woman is uniquely different; there are many women who have undergone FGC but who don’t report experiencingsexual challenges. Women’s sexuality is a complex integration of biological, physiological, psychological, social-cultural, and interpersonal factors. All these factors contribute to achieving sexual satisfaction. Orgasm is, in my opinion, the pleasure that people should experience during sexual engagement; it is one part of a woman’s sexual satisfaction. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “removal of, or damage to, highly sensitive genital tissue, especially the clitoris, may affect sexual sensitivity and lead to sexual problems.” The underlying effects on women who are affected by FGC in terms of their sexuality in regards to orgasm specifically can include pelvic inflammatory diseases, which contributes to the absence or reduction of orgasms. The disorder in a woman’s failed orgasm is called Female Orgasmic Disorder. Considering that sexual pleasure should be a human right, I think it is important for survivors to be supported in their healing after the trauma and pain of FGC, which often removes the ability for sexual pleasure. Healing Process In learning about all the experiences that FGC survivors can undergo related to sexual challenges, I thought it important to consider the healing process as well, and found that it can include: Mindfulness which involves pausing and reflecting during sexual activity to study your body’s behavior which can be key to the healing process. Mindfulness may allow the survivor to understand their body better and study ways of experiencing pleasure while still healing from physical and emotional scars. Somatic therapy involves the psychological process of healing the brain from traumatic experiences. It helps to release stress, tension, and trauma from the body. Physical and mental preparation before sex allows your brain and body to adjust from the activity so that pleasure can be achieved. Learning the erogenous zones and additional ways that one may feel pleasure/arousal. For Pelvic floor dysfunction, where either muscles in the pelvic floor are too weak or too tight, physical therapy can bring out the restoration process. Through exercises, pelvic pain can also be reduced. For survivors experiencing this condition, Sahiyo has been a key player in spreading information on pelvic pain. Sahiyo also hosts our Dear Maasi column, an anonymous advice column for all questions about FGC, sex, and relationships that can be a great resource for survivors and those supporting survivors. Sexual healing is not a destination; it is a process that does not involve a linear path, but rather a winding path with many possible forms of healing. For survivors, support is key, and we all can find ways to support those in our lives who have undergone this experience.

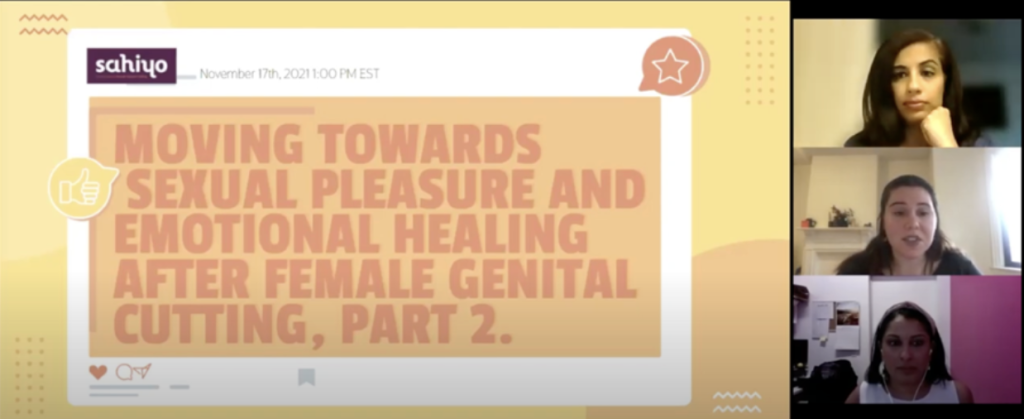

Reflecting on Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting Part 2

On November 17th, Sahiyo hosted part two of the ‘Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting’ webinar. Two specialist speakers helped to lead the webinar: Haddi Ceesey, a health educator on sexual and reproductive health, and Nazneen Vasi, an expert in physical and pelvic floor therapy. Nazneen began by asking the audience what the pelvic floor is and then explaining it comprises the external female genitalia. I was shocked to realise I wouldn’t have been able to answer if someone had asked me this question. The comprehensive detail that Nazneen went into very effectively emphasised how little we as women are taught about our own bodies. She also emphasized how important it is to understand the workings of the female body to fully appreciate how trauma is physically reflected in the body. Nazneen described how trauma to the pelvis, for example, can present as sexual pain, incontinence, or loss of organ support, which can result in prolapse. Female genital cutting (FGC) specifically can cause pelvic floor dysfunction, which presents as pelvic pain, weakened muscles, and constipation, among other things. It felt very important to learn about such specific consequences of FGC, in order to start grasping the suffering of so many women. The importance of advocating for our own public health was subsequently expressed, especially as there are so few healthcare practitioners who are trained specifically in the support system of the pelvic floor. It seemed to provide further evidence for the erasure of women in medicine and healthcare; when male bodies are seen as the universal norm, their symptoms and side effects are often automatically applied to all, and their female counterparts’ symptoms and side effects are all too often disregarded. This inequitable norm provides all the more reason to prioritise your own health, especially as a survivor, in order to move forward and reclaim one’s own body. You can read more about Nazneen’s work and Pelvic Floor Therapy in relation to FGC here. Haddi explored this journey to healing further, discussing general wellbeing and how FGC has been found to directly impact mental health, especially in young people. The physical problems resulting from FGC, such as pregnancy complications, period pains or poor sexual health, inevitably lead to a worsened quality of wellbeing; FGC survivors have often cited anxiety, stress and fear concerning sex and intimacy. When speaking to mothers, Haddi found that their concerns about sex stemmed from a fear of potential complications they would face having more children, based upon their previous difficult childbirths. Interestingly, many of the women surveyed wouldn’t even directly address sex; they would instead talk about marriage and let the rest be inferred. I thought that this very effectively highlighted a significant part of the problem as to why FGC still occurs – it is inevitably much more difficult to address this gender-based violence if practicing communities see sex and sexuality as a taboo, or as something private or shameful. It makes it a lot harder for survivors to be open about their sexual struggles stemming from FGC, or to get support in overcoming these issues. Haddi concluded her part of the webinar on a constructive note, focusing on how survivors can move forward in intimate relationships; she suggested increasing conversations about intimacy and pleasure within sexual partnerships, as well as with other survivors. Haddi explained that these women can learn a lot from each other alongside providing support. Additionally, it is clear that there is not nearly enough comprehensive legislation on FGC, and that it must include education and resources to help survivors live healthy and fulfilled reproductive and sexual lives. Finally, Haddi encouraged survivors to spend time with themselves and their partner, to explore their bodies and find different erogenous zones. There are also some very exciting developments currently in clitoral reconstruction and restoration, which specifically puts emphasis on regaining pleasure. Overall, I found the talk to be very positive and empowering. Both speakers went into important detail about the physical and psychological consequences that FGC can have on sexual and reproductive health, and both gave expert advice and multiple different methods to help survivors start to regain their sexuality. Watch the full event here. Read the transcript here. Watch Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting Part 1 here.

Upcoming Webinar: Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing Part 2

By Amela Tokić Last October, Sahiyo hosted a webinar called Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting. This provided an opportunity to hear from three inspirational speakers: psychotherapist and author Farzana Doctor, activist Sarian Karim-Kamara, and psychotherapist Joanna Vergoth, on female genital cutting (FGC), sexuality and its connection to mental health. The webinar jump-started an important discussion on ways survivors can begin to move towards their own sexual pleasure and emotional healing after FGC. Sahiyo didn’t hesitate to delve into difficult and taboo subjects surrounding FGC, such as psycho-social and mental impacts of FGC, and provided survivors and non-survivors a space to better understand the process of sexual and emotional healing after FGC. Coming this November, Sahiyo will be hosting a second part to the webinar: Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting Part 2. The webinar will dive deeper into these topics with three new expert panelists: Nazneen Vasi, pelvic floor therapist and founder of Body Harmony Physical Therapy. Manal Omar, founder of Across Red Lines, Haddi Ceesay, health educator and consultant for HEART Register for the event here: https://bit.ly/MovingFurther The event is open to anyone who wishes to attend. Watch the recording of the first webinar Read the transcript of the first webinar Read the blog post for the first webinar Read answers to questions from the first webinar The event is sponsored by Sahiyo.

Your questions answered: Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting

Last fall Sahiyo partnered with three award-winning and talented speakers Farzana Doctor, Sarian Karim-Kamara, and Joanna Vergoth to host Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting (FGC). During this webinar, we had the opportunity to hear from these speakers about the mental and emotional consequences of female genital cutting (FGC), how FGC can impact sexuality, and how survivors may be working toward healing. Our guests had a lot of questions for our speakers, some of which we were not able to answer during the webinar. Nevertheless, we felt these questions and their answers were important to share. Below you will find the answers licensed psychotherapist Joanna Vergoth graciously answered for our guests. If your question is not addressed below, you may find it answered later in the recorded portions provided by Sarian Karim-Kamara on the Sahiyo YouTube page or on the Dear Maasi page. Joanna Vergoth’s responses to participants’ questions: Do you have any strategies for breaking the taboo around FGM/C and how community-based organizations can work directly with community members to end the practice in the U.S.? Silence regarding FGM/C perpetuates the practice so it is important to find a way to broach the subject sensitively in order to encourage conversation. And, when working with community members, it is advisable to identify and recruit folks who support the abandonment of this practice in order to create dialogues that can help persuade proponents of the practice to reconsider their position. Also, sponsoring a community event that focuses on women’s health and well-being can provide an opening for discussion. In addition, showing a film about FGM/C, such as “Desert Flower,” or “The Cruel Cut,” can also open hearts and minds. Is part of the healing process ever confronting the person who betrayed you? Betrayal trauma occurs when the people a person depends on for survival significantly violate that person’s trust or well-being. It is understandable, then, that being cut by a trusted family member can have lifelong consequences with powerful emotions that can be difficult to process. Confronting the person who betrayed you can provide psychologically healing relief if your feelings are acknowledged and respected and if the ensuing conversation supports an honest discussion. However, every situation is unique and not everyone will feel the need or desire for confrontation. One can heal without confrontation. It all depends on the individual survivor and her particular circumstances. I hope you can answer this question, please. Is it normal to not feel any impact by FGM? I am Iraqi and had FGM when I was around 7. I have no memories of this. I don’t have problems climaxing, and I am worried I may be blocking all of this out but I have no recollection of this at all. Although post-traumatic stress symptoms can remain in remission for years, I don’t think you should think you have a problem because you can’t remember undergoing FGM. There are many women who do not remember their FGM/C [experience]. And, FGM/C is not necessarily an impediment to sexual function. In fact, many women report that they have no difficulties experiencing orgasm. How do you offer community support to white women who have survived FGC from surviving cults, since their experience is different from women of color who may have community/cultural support? Unfortunately, I do not know of any community support for Caucasian FGC survivors who have also survived cults. Here is the first link and the second link of resources for cult survivors. Hopefully, these women may be able to find support and other FGC affected survivors. Any experience with sexuality after clitoral restoration? The procedure, often called clitoral reconstruction or restoration, is viewed with caution by some medical experts. The World Health Organization says that while there are some promising reports that the operation may relieve pain, there is not yet enough evidence of safety and effectiveness. The organization advises against raising unrealistic expectations, especially for women seeking sexual improvement. However, that being said, a recent systematic review evaluated the effects of reconstructive surgery. The results indicate that about three women out of four regain a visible clitoris. Self-reported improvements in pain during sex, clitoral function/pleasure, orgasm, and desire are in the 43– 63% range; but up to 22% reported a worsening in sexual outcomes. It is important to remember that female sexuality is a complex integration of biological, physiological, psychological, sociocultural, and interpersonal factors that contribute to a combined experience of physical, emotional, and relational satisfaction. And within this combination of factors, every woman is uniquely different. Hear about one FGM/C survivor’s successful experience of her clitoral restoration surgery.

Sahiyo staff spoke in a symposia entitled Mothers and daughters: continuity, love, fear and belonging

Sahiyo Communications Coordinator Lara Kingstone and co-founder Mariya Taher were honored to speak on behalf of Sahiyo in a symposia entitled, Patriarchal Inscriptions: Female Bodies Contested, Invaded, Defended & Owned, hosted by King’s College London Faculty of Arts and Humanities. [youtube url=”https://youtu.be/PZ3YZQxc7FM”]W The session that Sahiyo participated in served to address feminism, survivors’ relationships with mothers, other forms of gender-based violence and abuse, as well as systemic injustice. The symposia in general served to address the following questions: “Feminism has made the exploration of relations between mothers and daughters central to its project. How are these considered fraught, damaged, broken, or, in the eyes of FGM-supporters, strengthened by clitoridectomy? How does FGM compare to other abuses women endure that fracture their inclination to identify and support one another, instead of becoming invested in, or complicit with, systemic injustice?” Taher and Kingstone discussed and presented Sahiyo’s Voices to End FGM/C: Using Storytelling to Shift Social Norms & Enhance Prevention as part of the panel on Mothers and daughters: continuity, love, fear and belonging. Many storytellers and survivors explore fraught or strengthened relationships with their mothers in their digital videos as part of the Voices to End FGM/C program in collaboration with StoryCenter. By sharing these stories with participants, Sahiyo aimed to further understanding regarding the deeply complex mother-daughter relationship in the context of FGM/C. Read the full program.

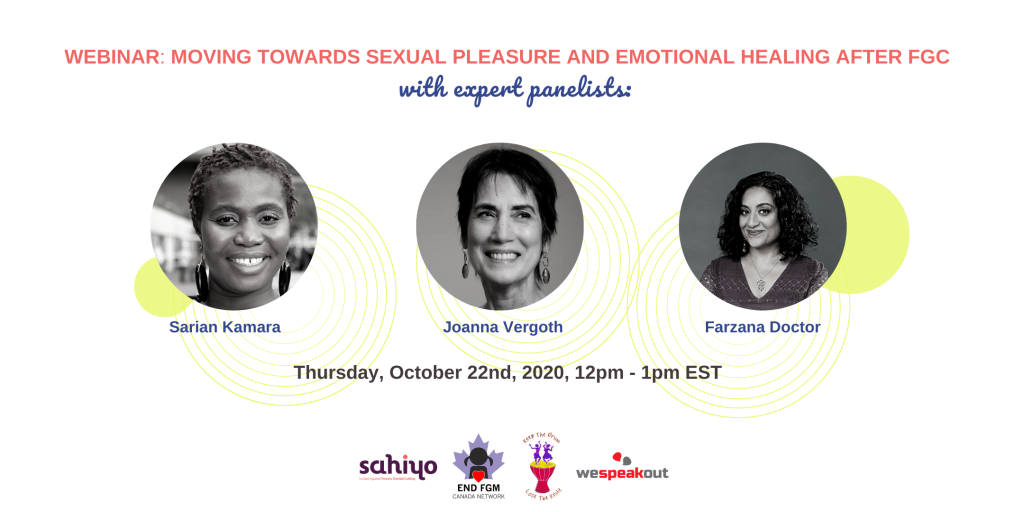

A Reflection on Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting

By Cate Cox On Thursday, October 22nd, Sahiyo partnered with three award-winning and multi-talented speakers Farzana Doctor, Sarian Karim-Kamara, and Joanna Vergoth to host Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting (FGC). During this webinar, we had the opportunity to hear from these speakers about the mental and emotional consequences of FGC, how FGC can impact sexuality, and how survivors may be working toward healing. Passionate, honest, and bold, this webinar explored some of the most difficult and taboo subjects surrounding FGC, and allowed survivors and non-survivors alike space to better understand the process of healing after FGC. Mariya Taher, a co-founder of Sahiyo and U.S. Executive Director, guided our speakers through conversations about the psycho-sexual impacts of FGC and how they have worked to help survivors heal. Vergoth, a trained psychoanalyst, gave the audience a detailed and uncensored explanation of how the physical and mental impacts of FGC can make it difficult for survivors to experience sexual pleasure, and what methods survivors can use to move toward their own emotional and sexual healing. Karim-Kamara boldly explored her own experience with sexual healing, and spoke of her struggles and victories in a way that moved many in the audience to tears. Finally, Doctor also explored her own process of sexual healing and how her latest novel, Seven, gives readers a greater view into the complexities and struggles of sexual healing for survivors of FGC. Certainly, one of the most powerful and enjoyable moments of the webinar was the opportunity the audience had to ask the panelists questions at the end. We spoke to two audience members about their questions. The first audience member, who was a survivor herself, asked the speakers for advice on whether or not one should undergo the surgical process of clitoral restoration. Each speaker had a slightly different answer to this question, but the heart of each of their messages was the same: explore your own body first, find a trusting partner to help you, and read up about healing before you make a decision — but ultimately the decision is yours alone to make. Our second audience member asked the speakers to explore how to create a safe and educational space for young people to heal from FGC and continue activism to end the practice. The speakers explored their roles in their organizational and activism efforts. For those who are interested in learning more about their work, our speakers helped to found forma, Keep the Drums and Lose the Knife, The End FGM/C Canada Network, and WeSpeakOut. From exploring the intricacies of sexuality and mental health, what it means to heal from FGC, and how to mobilize a healing movement, Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After Female Genital Cutting was a powerful and radical event. With guests hailing from the United States, the Netherlands, India, Canada, Iran, and other countries, it is clear this event is part of a global movement that is pushing for FGC activism to expand outside the realm of ending this practice to include a movement focused on helping survivors move toward healing. For those who were unable to attend, or would simply like to learn more about this event, the transcript and recording of this event are attached below. Watch the recording of this event here. Read the transcript here.

From Saving Safa to Seven: How authors use writing to shed light on FGC

By Cate Cox “Without our work, the issue would quickly be swept under the carpet — and so we carry on.” —Waris Dirie, Saving Safa It wasn’t until my first year at university before I was asked to critically engage with the issue of female genital cutting (FGC). Up until then what I knew about FGC I knew from overheard conversations between my parents and their colleagues, from snippets of news briefs and CNN articles that flashed across my computer screen. If you’d asked me to name an activist working to end FGC, my answer would have been something along the lines of someone working with the United Nations. Yet when I saw Waris Dirie’s novel, Saving Safa, on the reading list for my leadership class, I immediately recognized it. The young, but strong face of Safa having become almost synonymous with the global fight to end FGC. I knew her face, yet I didn’t know her story. As much as I agreed that the practice of FGC ought to end, I’d never been asked, or asked myself, to sit down and engage with the stories and lessons of the actual activists on the front lines working to end it. As I made my way through Dirie’s critically acclaimed sixth novel, I began to understand how little I understood. I realized how much my perception of FGC had been shaped by the position of an outsider looking in, instead of as a listener. We only spent two weeks in my class covering Saving Safa, but they are two weeks for which I am extremely grateful. Reading Saving Safa helped expand my understanding of FGC, the communities who practice it, and the challenges faced by people trying to end it. This 276-page book, not written for doctors or scholars or researchers, but accessible to ordinary people like me, had managed to change my world view in a mere two weeks. The success of Dirie’s many novels about this subject highlights the power of writing, and storytelling in general, as a weapon to encourage the abandonment of FGC. Writing allows people a glimpse into the thoughts and feelings of the communities that practice it. It allows us an accessible way to understand the issues and complexities of ending the practice. Most importantly, it brings to light the stories of such an often overlooked and ignored practice. Writing also has the power to allow survivors to see their own stories reflected, and gives both the author and the reader a space to heal. But the legacy of FGC and writing doesn’t end with Dirie. New and emerging writers are taking the torch to use writing to help shift the narratives around FGC. One of those writers is Farzana Doctor, author of the upcoming novel, Seven. In her novel, Doctor follows the story of Sharifa and the unrest that is gripping the Dawoodi-Bohra community as activists grow louder in their fight to end the practice of khatna or FGC. Doctor’s writing never shies away from highlighting the complications and difficulties that come with trying to end the practice. These reviews shine a light on Doctor’s intentions for Seven: “In her grand tradition, Farzana Doctor once again pushes us forward with nuanced, layered, inter-generational prose, to bring visibility to an important social issue. An urgent and passionate read.”—Vivek Shraya, author of I’m Afraid of Men and The Subtweet “Seven is an intimate, gutsy feminist novel that exposes the lasting, individual impacts of making women’s bodies fodder for displays of religious obeisance.”—Michelle Anne Schingler, FOREWORD Reviews These reviews summarize the value that writing has in education and advocacy around FGC. The work of Doctor, and other authors like her, is helping to continue to push against the boundaries of silence that keep this practice so often trapped in the shadows. She is fighting to continue the tradition started so many years ago by Dirie in using writing to shed light on the topic of FGC. Doctor will speak about her work and activism at the Sahiyo webinar, Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After FGC, on October 22nd, at 12 noon. Expert panelists Joanna Vergoth and Sarian Karim-Kamara will shed light on these subjects using their professional and personal experiences. Register for this event today: https://bit.ly/HealingAfterFGC The event is co-sponsored by Sahiyo, WeSpeakOut, The End FGM/C Canada Network, forma, and Keep the Drums Lose the Knife. For those interested in learning more about FGC, you can purchase a copy of Seven through the links below or bookstores: Re US: bit.ly/orderSevenUS Canada: bit.ly/orderseven Audiobook: bit.ly/sevenaudiobook

On the path to healing: My journey after experiencing female genital cutting

By Anonymous Country of Residence: United States Every woman that has been cut has a story to tell. I tell my story not to offer a universal account of female genital cutting (FGC), but one that is specific to me. At a young age, I underwent Type II female genital cutting, known specifically as “taharah” (purification) within the Egyptian community, in which only part of the clitoral hood was removed and partial removal of the labia minora/majora. The taharah took place in Cairo, Egypt, while visiting relatives. This was the second time I visited my parent’s homeland. My parents were unaware, or at least this is what I’d like to believe, of what had occurred, as my sister was in a coma at the time and her prognosis was poor. They agreed that I travel to their homeland with my auntie to avoid the negative effects of witnessing what my sister was going through. My aunties had convinced me that this was a rite of passage, and what I was about to embark on would make me a “woman.” One week after arriving in Cairo, my auntie took me to a medical office where a doctor performed the surgery. She remained in the room while I underwent FGC, while my other auntie waited by the phone to hear the “good news.” I have no recollection of the surgery, as I was under anesthesia. However, I awoke to excruciating pain that would last for weeks. I remember my family members visiting to celebrate—bearing money and gifts. Upon returning home my parents realized that something was different about me. Already small-framed, I had lost ten pounds. I notified them of what occurred, and I remember them speaking with my aunties. However, the details of the discussion were unknown to me. In 2001, while taking a women’s psychology course, I learned that FGC was considered a human rights violation. Students in the class, including those from countries where this was practiced, were surprised and “disgusted” that FGC continued to be practiced. I was taken aback, as I had assumed this was a custom that many practiced. I began opening up to female friends from similar and varying backgrounds. I quickly discovered I was alone in having had it done to me. I started looking into the practice of FGC and found that there were many factors contributing to the perpetuation of FGC. Some linked it to geographical location, religion, customs, sexuality, marriageability and education. I realized this was a complicated custom that could not simply be thought of as being continued by “ignorant” people. In fact, much of my family are college educated, wealthy, and progressive in terms of religion, and advocate for the rights of women. However, the reasons given for its continuation had been rationalized by them and somehow given cultural significance. I needed answers, and began a long journey that would ultimately lead to my decision to become a social worker, and work with women who have also been cut. Mapping the Healing Journey I was left feeling extremely confused, particularly as most of my family had decided to discontinue the practice due to religious reasons (stating that FGC is “haram” or a sin, and is not a “sunnah” or religious obligation. I searched for answers—or perhaps a place where I would feel accepted and learn to accept myself. I immediately reached out to gynecologists, gender violence organizations, and social workers. Much to my dismay, all were unaware of the FGC practice. Gynecologists stared blankly at my genitals stating, “At first glance, it looks intact.” However, they were unsure the extent of the “damage” done. Gender violence organizations stated that they dealt with different forms of gender violence. “This isn’t something we specialize in,” I was told. They referred me to organizations that had more familiarity. However, they were located overseas. Social workers were unfamiliar with the practice but verbalized their strong beliefs about it. They reacted with words such as “disgusting,” “barbaric,” and “horrific.” They “encouraged” and “empowered” me to advocate for change against the oppressive practice that they assumed was justified by Islam and patriarchal oppression. They also questioned the reasons that parents would allow for such a thing to happen to their little girl. This was extremely difficult to hear given my close relationship with my parents. I walked away feeling judged, ashamed, and defective. For the first time, I began to experience symptoms of depression, which led me to become more embarrassed and secretive about what had occurred. Approximately eight years later, while reading a newspaper article, I came across the name of a Sudanese woman who started a grassroots organization for women who have been cut. The only experience I knew was one in which providers gawked at me when I told them what had occurred. I reached out to this woman, and she invited me to dinner to speak on a more personal level. Upon arriving to the restaurant, I was greeted with a warm smile. For the first hour of our meeting, she did not bring up the conversation of FGC. Surprised, I inquired, “So are we going to talk about… you know.” She replied, “When you’re ready, I am here to listen.” For the first time in a long time, I felt acknowledged, understood, accepted, and supported. We all begin our journey of healing somewhere. I am delighted to be a part of the Sahiyo team—and truly look forward to being a part of the healing process for others.

Art: A Tool for Healing and Dialogue with Communities Affected by FGM

By Naomi Rosen Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C), although often surrounded by secrecy and taboo, is now discussed more frequently in the media. Activist groups such as Sahiyo are taking great steps to heighten awareness and dialogue, within relational, familial, and community contexts, because the practice is often hidden, shameful, and the subject is therefore avoided. In many cultures and contexts, it is already difficult to talk about women’s bodies and women’s sexuality, but when talking about FGM/C, the discomfort and silence are compounded by generations of tradition, ideas about what it means to be feminine and pure, religious beliefs, and a multitude of other reasons dependent on geographical, cultural, religious, and personal contexts. Art is a helpful tool and medium in supporting communities affected by FGM/C to express and explore the topic of FGM/C in a way that feels less threatening and can allow for more openness and dialogue. Creative practices allow for what is secret and taboo to be brought to light. It encourages the exploration of what is unexplainable through words, and allows for the unheard to be spoken aloud, and for individuals to truly listen to and empathize with one another. Art can heal emotional wounds through the creation of meaning-making and metaphor. This year as a German Chancellor Fellow through the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and under the guidance of Tobe Levin von Gleichen, I have been interviewing organizations and individuals in Germany, but also more broadly in Europe and the United States, to explore how the arts can serve as a tool for trauma healing and dialogue with communities affected by FGM/C and other forms of Gender-Based Violence. I have learned creative practices are utilized with communities affected by FGM/C and the unique role the arts can serve. The purpose of compiling this information through my various interviews is to create a handbook to support organizations, practitioners, and direct-service providers in utilizing art and creative approaches in their daily practice. The handbook seeks to expand the definition of “art” to include storytelling, gardening, cooking, and more. It will suggest unique ways to use the arts, from generating intergenerational dialogue to creating spaces for prevention and awareness-raising in gender violence. The resulting publication will also contain descriptions of the organizations I have interviewed and their contact information so that these organizations can be connected with one another and to other individuals for future collaboration and knowledge-sharing. While FGM/C is a custom that for generations has been hidden, the utilization of the arts can create the opportunity for healing from potential traumatic responses as a result of the practice, as well as fostering dialogue that may not be possible otherwise. For more information, please contact Naomi Rosen at naomirrosen@gmail.com For more information on Tobe Levin von Gleichen and her publishing company, UnCut Voices Press, visit the blog https://uncutvoices.wordpress.com ———————————————————————- Naomi Rosen lives in Frankfurt, Germany. After completing at B.S. in Theater at Northwestern University, she was a Northwestern University Public Interest Program Fellow (NUPIP), where she witnesses the role art and theater can play in healing and change in working with at-risk youth. She went on to pursue her Masters in Social Work at University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration where she specialized in Trauma-Informed Practice, Creative Arts Therapies, LGBTQ Affirmative Practice, and Multicultural, Multisystemic Practice with trainings at Live Oak Therapy Practice. Naomi is currently a German Chancellor Fellow through the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation where she is writing a handbook about arts-based methods to support communities affected by FGM and other forms of Gender-Based Violence.