Training the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium on FGC in honor of Zero Tolerance Day for FGC.

We are delighted to share insights from a training session hosted by Sahiyo in partnership with the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium (SF-DVC) on February 8, 2024. Our “FGC-101,” training aimed to shed light on the complex issue of female genital cutting (FGC) and uplift the ongoing collaborative efforts between Sahiyo and AWS on expanding gender-based violence (GBV) services to support survivors of FGC. This training was delivered to 16 advocates and community-based attorneys from the San Francisco Bay area. Led by Sahiyo’s Executive Director, Mariya Taher, and T&TA Coordinator, Aries Nuño, and Orchid Pusey from the Asian Women’s Shelter the training provided a comprehensive overview of FGC, including its physical and psychological impacts, global and U.S. perspectives, effective strategies for supporting survivors. These positive reflections from the participants underscored the importance of our collaborative efforts to address GBV and the value of providing informative and engaging educational experiences: “Thank you for your work! Looking forward to learning more and I appreciate AWS’s leadership on this matter.” “Thank you for a super engaging presentation! I learned a lot.” This initiative is part of our ongoing commitment to educate, engage, and empower advocates, enhancing their ability to offer crucial services to those affected by FGC. We extend our gratitude to the participants for their active engagement and to the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium for their partnership! For more training and technical assistance information contact aries@sahiyo.org.

Mariya Featured on Maitri’s Between Friends Podcast

This past month Sahiyos co-founder and U.S. Executive Director, Mariya Taher participated in an episode of Maitri’s, Between Friends Podcast. The episode focused on the taboos surrounding FGC and why speaking about the practice, both in public and community settings is vital to help end the practice. Maitri is an organization that supports South Asian women who have been through or are currently in situations of domestic violence. Over the years their work has expanded to include providing survivors with mental and legal support, creating training programs, and educating communities on the impacts of domestic violence. To learn more about Maitri’s work, click here. Listen to Mariya’s episode here: YouTube Spotify SoundCloud Link

FGC 101 Training for Volunteers at Asian Women’s Shelter

As part of Sahiyo’s long-standing collaboration with the Asian Women’s Shelter (AWS), a training session was held on October 28th to empower incoming volunteers. The training aimed to equip AWS’s dedicated volunteers with essential knowledge and foundational skills for understanding the pressing issue of female genital cutting (FGC), both globally and within their communities in the United States. The training was not about transforming volunteers into experts, but rather about creating a safe and nurturing space for learning and dialogue; Sahiyo and AWS recognize the importance of both fostering an environment where volunteers feel encouraged to learn more about FGC, and providing them with resources to continue the conversation in their communities. Throughout the presentation, an atmosphere of open dialogue prevailed. Volunteers actively engaged in the session, asking numerous questions and reflecting on the content. This dynamic exchange of ideas and information is crucial in breaking the silence that often shrouds FGC. By asking questions and reflecting on the material, the volunteers are taking first steps in becoming advocates for survivors and being able to raise awareness in their communities. The partnership between Sahiyo and AWS is not only about knowledge transfer, but also about building a strong foundation of empathy, understanding, and support. We believe in the power of collective learning and collaboration, and will continue our commitment to empowering voices, strengthening communities, and ending the cycle of silence surrounding FGC.

Bridgewell Organizes Training for Social Workers

Social workers are an important stakeholder group to provide training for when it comes to supporting survivors of female genital cutting (FGC), and building the cultural competency of social workers is vital. Within the U.S., however, many social workers, advocates, and social service providers are not adequately equipped to address FGC in their practice. On Nov 8, in collaboration with Sahiyo and the US Network to End FGM/C Network, Bridgewell organized a training that provided continuing education units (CEUs) to social workers; the training gave an introductory foundation for understanding what FGC is, including its prevalence in the U.S. and globally, as well as and the role of social workers in addressing and responding to this issue. The workshop shared key competencies and best practices for working with survivors of FGC and supported increasing attendees’ confidence in talking about and addressing FGC in their practice.

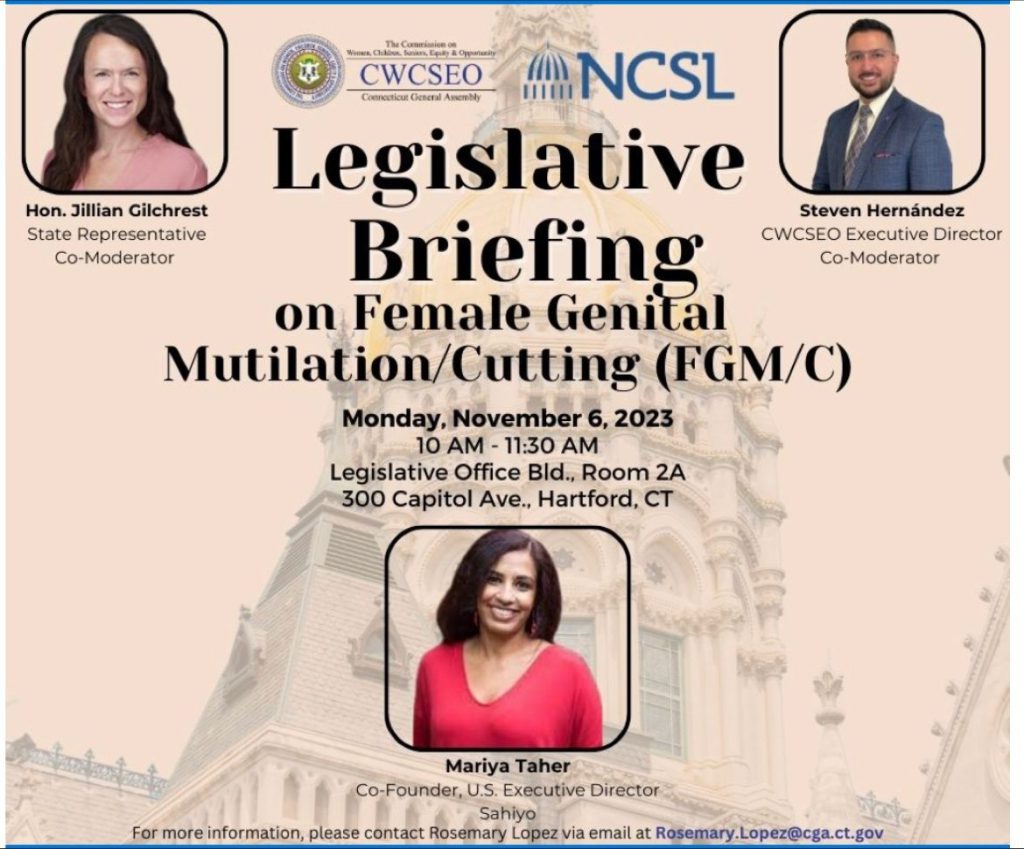

Legislative Roundtable held in Connecticut to discuss FGC

On November 6th, Sahiyo, as part of the Connecticut Coalition to End FGM/C, supported a legislative briefing on the topic of female genital cutting (FGC) hosted by the Commission on Women, Children, Seniors, Equity and Opportunity (CWCSEO) and Connecticut Representative Jillian Gilchrest. Special guests included Mariya Taher, Co-Founder and U.S. Executive Director of Sahiyo, as well as experts from the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). Connecticut remains one of only 9 states in the U.S. yet to address this human rights violation in any manner; this briefing provided insights into the legislative landscape surrounding FGC in the U.S., as well as progress made, challenges faced, and how to move forward in addressing FGC. NCSL also summarized the laws addressing FGC in the 41 states. The Connecticut Coalition to End FGM/C will continue to advocate for a bill to be introduced into this next legislative cycle, starting in January 2024, in hopes that CT legislation will recognize the need to promote a safer, healthier future for all in the state. Learn more about Sahiyo’s policy work here.

Exploring FGC with GBV Service Providers

Female genital cutting (FGC) is an often overlooked facet of gender-based violence (GBV) in the United States. On November 2nd, Sahiyo joined forces with South Asian SOAR to host a training session tailored for service providers in the GBV sector. Facilitators delved into the complexities of FGC, providing attendees with insights into FGC’s various forms and the emotional and physical impacts of this harmful practice. Compelling stories from survivors, shared through Sahiyo’s Voices to End FGM/C project, shed light on the intersectional identities of survivors and their emotional journeys, as well as their inspiring advocacy efforts. The training also explored the cultural contexts of FGC, examining its presence globally, and more specifically in the U.S., receiving an overview of current U.S. laws related to FGC. A reflection discussion prompted conversations about effective ways to engage with the general public and survivors on the issue of FGC. With more than 15 SOAR coalition members in attendance, this knowledge equips service providers to offer comprehensive support, bridging the understanding gap surrounding the complexities of FGC. As one participant stated: This session opened the other side of GBV, which is often absent from our day-to-day narratives. Thank you????. If your organization is interested in inviting Sahiyo to conduct a training session, please contact Sahiyo’s Training and Technical Assistance Coordinator Aries Nuño for more information.

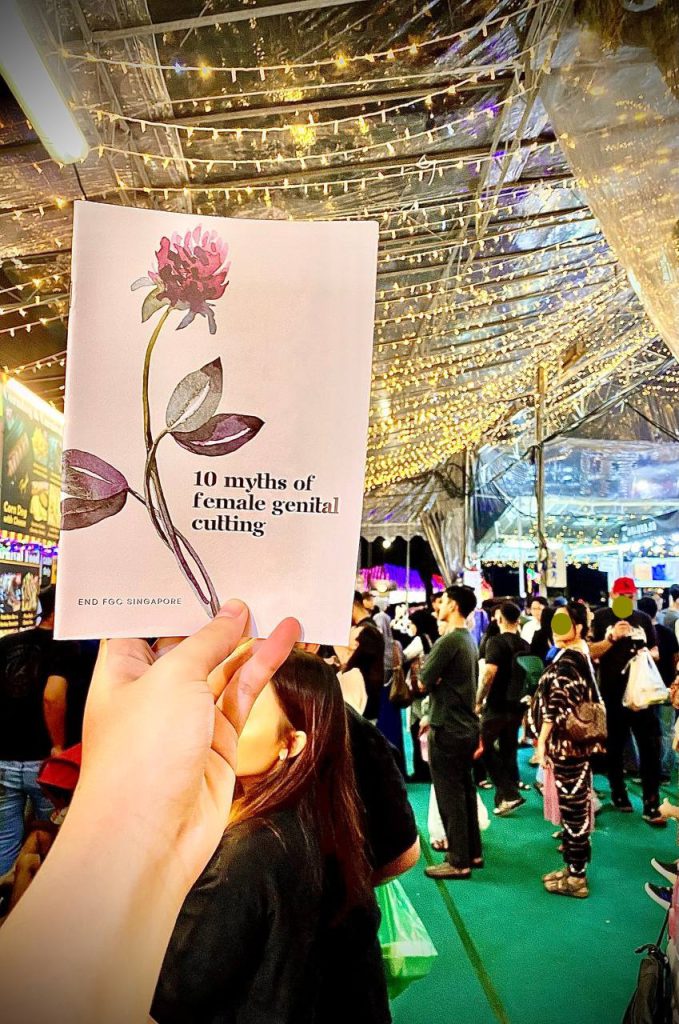

Activist Saza Faradilla and End FGC Singapore spread awareness about FGC

By Megan Seaver An essential part of the work to end female genital cutting (FGC) is to engage in community-based activism, which means to serve a specific group of people with a specific set of needs and values. Sahiyo’s Editorial Assistant Urvashi Sharma interviewed Saza Faradilla, a community-based activist in Singapore, to discuss how she engages in community-based activism when it comes to the campaign to end FGC. Saza began the conversation with an explanation for her centralized, community-based approach to ending FGC in Singapore: “We started End FGC Singapore in November 2020, primarily because we believed that a cohesive, more ordered force needed to be established to bring an end to this practice.” From there, the first step was to “raise awareness among the Muslim community,” then “to lobby officials who occupy high positions of power,” and finally “to facilitate solidarity among Singaporeans in order to create an understanding that this…is a Singapore health problem.” End FGC Singapore uses educational methods to challenge stereotypes surrounding FGC, including discussing how FGC should not be interpreted as a religious mandate for Muslim women. As part of their programs last year, End FGC Singapore decided that during the holy month of Ramadan, they would bring awareness to FGC through hosting a public awareness campaign. “This isn’t the first time we’re doing this – last year we distributed our booklets outside the mosque, but decided to take it to the next level this year in order to reach out to the people we’re trying to influence.” The bazaar is set up during Ramdan which consists of food, vendors, and activities for families. Saza reflected on choosing the Bazaar, explaining that it was the event to pass out educational booklets on FGC because “the Bazaar is younger, attracts a larger crowd, and is more hip. It’s important for effective activism to be able to segment our audience and then provide targeted marketing. Those are the people whose minds we are trying to broaden and influence.” End FGC Singapore sought to speak with the younger generation of Muslims in Singapore because they felt that a younger audience would be more receptive and open minded to criticizing the practice of FGC; focusing on younger Singaporeans also gives End FGC Singapore the opportunity to create generational change. These young people will one day hold positions of power in their communities, and because they have been exposed to End FGC Singapore’s activism, there is a greater chance they may put forward laws and ideas that help end FGC. Saza also explored different people reactions when being handed the booklet: “Common questions that we receive are along the lines of, is this practice required in Islam, is this practice safe if it’s done by a doctor, is sunat perempuan the same as FGM, etc. So we addressed the issue from a health perspective, a religious perspective, and then a cultural perspective.” End FGC Singapore have set themselves up to provide future activist programs because they have established a common connection within their community. End FGC Singapore also made sure that the information in the booklet was educational, while still appealing to inclusion of the Muslim community. But in distributing the booklet at the Bazaar, they did run into some challenges. “Most people are quite shocked at first because they don’t expect to talk about FGC in a Bazaar.” Saza’s work has also gained media attention, as the booklet program was featured in an article published by Mediacorp Today. However, not all the feedback has been positive: “The Ramadan Bazaar organizers reached out to us after the article came out and messaged me saying that I’m not supposed to do this because I didn’t get approval (in Singapore you need to get approval for everything). However, it is legal to give out any non-political booklets in all public spaces. So we had a meeting with them arguing that the Ramadan Bazaar is a public space.” Despite the pushback, End FGC Singapore’s use of a public space to deliver the booklets is a testament of their commitment to community-based activism. Saza and her team know their community and have tailored their community engagement work towards the youth, who they hope will understand the harms of FGC and work towards prevention of it for future generations. This community-centered approach creates space for dialogue between communities and activist organizations, which is vital to ending the practice of FGC.

Volunteer spotlight: Development Intern Shatize Pope

Shatize is a senior working towards her BA at Columbia University in New York. She is majoring in Human Rights with a specialisation in women’s studies and looking forward to attending NYU for law school to specialise in international law with the hopes of one day working for The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Shatize is very passionate about creating a safe space for women and young girls to be able to thrive in what is labelled a man’s world. She has been an advocate fighting for the elimination of female genital cutting (FGC) as it violates the human rights of women. As a mother to a young daughter, she is teaching her to always stand up for what is right no matter the obstacles that await. Shatize is looking forward to working for Sahiyo and educating those unfamiliar with the harm FGC causes millions of women and young girls daily. She strongly believes that we can put a stop to FGC and empower those who have been affected by it. What was your experience of learning about female genital cutting (FGC) for the first time? The first time I learned about female genital cutting (FGC), I was around 10 or 11 years old at a church retreat. There, I made a new friend from Africa who had just come to the United States; she was my age. I asked why she was here in the U.S. without her mom, and she began to explain that her family had sent her away so she didn’t end up like her older sister, who had died from being forced to undergo FGC. When I later asked my mom what FGC was, she told me it was a bad thing bad men do to girls and women. I looked it up for myself and was shocked to learn that a human would do such a thing to another human. From that day, I vowed a life of service to women and girls around the world. When and how did you first get involved with Sahiyo? I am currently studying Human Rights at Columbia University with a concentration in Women’s Studies. I began looking for an internship that focused on protecting women, and that is how I came across Sahiyo; I quickly knew this was the place for me. The work Sahiyo is doing to protect women and girls from FGC is what I have dedicated my life to, and I want to protectas many women and girls from this human rights violation. What does your work with Sahiyo involve? As a development intern, I, along with the other amazing interns, help draft grant proposals and conduct research on funding for the many different outreach programs Sahiyo has to support survivors of FGC. How has your involvement with Sahiyo impacted your life? My involvement with Sahiyo has reassured me that working towards the protection of women’s and girls’ human rights is my purpose in life. I have a daughter, and I want her to grow up in a world that values her, not a world where she is considered less than because of her anatomy. What words of wisdom would you like to share with others who may be interested in supporting Sahiyo and the movement against FGC? Sahiyo is giving a voice to the voiceless while bringing awareness to the harms being committed against women and girls. Supporting Sahiyo will allow a survivor to get help, tell their story, and help stop the practice of FGC. Human Rights are universal, and everyone has the right to protection; Sahiyo is creating a safe space for those who otherwise do not have it.

Women should not be harmed because of societal norms

By Sakshi Rajani Age: 17 Country: India Female genital cutting (FGC): the term sounded ruthless the first time I heard it. It was not long ago that I was introduced to this term. While going through my Instagram feed, I read a story about a law student who was spreading awareness about FGC, and I was clueless about what it was. Immediately I searched this issue online and learned how serious it was. Then, I pondered why I hadn’t known about it earlier. Why had no one around me talked about it? Upon researching it further, I came to know how deeply rooted this problem was in communities and cultures. My will to do something to end it became stronger. I looked for organisations working to end FGC and came across Sahiyo. I soon joined the organisation. The first time I spoke about FGC to my friends they said, “What is that?” I wasn’t surprised by their reaction because I, too, was unfamiliar with it. I asked them to research it on their own, and then I explained more about the harms. I told them the World Health Organization and the United Nations declared FGC a human rights violation. Then I introduced them to the groundbreaking Mumkin app created by two co-founders of Sahiyo, Priya Goswami and Aarefa Johari, where my friends could learn more valuable information about this issue. What are the hurdles in encouraging abandonment of or ending FGC? FGC is also often seen as a necessary ritual for initiation into womanhood and can be linked to cultural ideals of femininity, purity and modesty. A strong incentive to continue the practice is family pressure to adhere to conventional social norms. Women who break from this social norm can face condemnation, abuse and rejection from family or community members. Patriarchal society can help perpetuate it generation after generation. Female genital cutting should stop immediately, as a woman should have full rights over her body and no woman should be harmed because of societal norms and expectations. I am now an advocate to make sure FGC ends.

A note on terminology and why Sahiyo uses FGC

By Mariya Taher When I was in graduate school in 2008 for my Master of School Work degree, I began seriously and thoroughly researching the topic of Female Genital Cutting (FGC). Some of you reading this blog might already be aware of my personal connection to the issue due to the research and writings I have been doing on this issue for close to nine years now. (See more at Underground: American Who Underwent Female Genital Mutilation Comes Forward to Help Others). Upon researching FGC, I learned that there were many different terms given to the practice. Terms such as Female Circumcision, Female Genital Mutilation, Female Genital Cutting, Female Genital Surgeries, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, Khatna, and other native terms used by other communities who continued FGC. The terminology used for this practice has been the subject of debate amongst academics, activists, as well as the communities continuing the practice as well. However, the debate does not revolve around what is the correct name but relates to the viewpoint an individual has towards understanding the practice and their feelings towards the perpetuation of the practice. In other words, for those continuing the practice, colloquial terms like khatna or female circumcision are preferred. Many activists working to end the practice of FGC choose to use the term Female Genital Mutilation, believing that this term correctly identifies the harm being done to a girl child’s genitalia. None of these terms are incorrect. They all refer to the same practice. And when Sahiyo works with community members, we use the terminology that they use to refer to the practice. This means if someone uses the term ‘khatna’, we use khatna. If someone uses the term female genital mutilation, we use female genital mutilation. There are reasons, however, that we do choose to use female genital cutting or FGC when referring to the practice. Dawoodi Bohras use the word “khatna” or circumcision to refer to the removal of the prepuce from the genitalia of both boys and girls. There is a sentiment amongst some in the community, that the form of “female circumcision” practiced in the Dawoodi Bohra community is in no way related to “FGM” as recognized by World Health Organization or as practiced in many African countries. Sahiyo believes, however, that “female circumcision” cannot be directly compared with male circumcision. We choose, therefore, in large part to use the term FGC or khatna because we are attempting to work with the community and we recognize that if in our everyday language we use FGM, it makes our work much more difficult — we know from research and best practices, that to engage in dialogue and to create social change, we can not come from a hostile position and some community members view the term mutilation with suspicion. This suspicion, in turn, makes it difficult for us to engage with people willing to discuss the topic. Sahiyo also recognizes that the term ‘mutilation’ comes with the connotation of ‘intending to harm’ and as activists engaging in dialogue with communities to abandon the practice, by not using ‘mutliation’ we recognize that communities are not intending to harm their daughters. Rather they may continue FGC because they truly believe it is in the girl’s best interest and/or they may feel pressured into having FGC done on their daughter by others in the community. The term ‘mutilation’ can be riddled with a judgemental tone which can work against FGC activists working to end the practice as Gannon Gillespie mentions on Tostan’s website: We should remember that all of us, no matter where we are from, tend to greet judgmental outsiders in similar ways. When our beliefs and actions are challenged or condemned by a stranger, we are likely to become defensive; rather than taking their concerns to heart, we view their accusation as an unwarranted and uninformed attack on our character. We certainly won’t feel inclined to change in order to satisfy this judgmental critic; we may even respond by holding on more tightly to the belief or action being questioned. Our experience has shown us that it is dialog and discussion that can lead to change, and dialog requires a relationship of trust and respect. But calling the practice “mutilation” prevents this relationship from developing and invites defensiveness rather than productive discourse. Besides these reasonings, a recent report by Islamic Relief Canada, Female Genital Cutting in Indonesia: A Field Study, showcases that specific terminology can also lead to retraumatization of survivors as the quote below from the study demonstrates: While Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) appears to be the term used most frequently by international agencies, experiences from community-based interventions indicate that the term ‘mutilation’ can, in some instances, actually add to the traumatisation of an individual. Girls and women who have undergone FGC can feel victimised, stigmatised and offended by the word ‘mutilation’ and its derogatory connotations. In general, it is important that any intervention strategies do not actually add to the trauma already felt by females who have had to undergo the practice, and referring to people as ‘mutilated’ – while correctly identifying the severity of the practice – has the potential of traumatising sufferers even more. Sahiyo recognizes that to work at the community level and to advocate for the abandonment of FGC, we must first acknowledge that FGC is viewed as a social norm in practicing communities. Dialogue and discussion can only occur if communities themselves are willing to engage with us, and through our own work, we have learned to understand the importance of looking at our language choices. To read more on the use of FGC terminology, please visit Tostan FAQ: FGC vs. FGM.