The forgotten history of female genital cutting in the United States

By: Sara Khattak Female genital cutting (FGC) is a practice involving the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons. While FGC is a form of gender-based violence that is often mistakenly understood to only occur in certain cultural traditions in Africa and the Middle East, the occurrence of FGC has a history in the U.S. that is less widely known. Understanding the history of FGC in the U.S. is crucial for recognizing the global nature and impact of FGC, and for understanding how to address and end the harmful practice. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, FGC was practiced in the U.S. and U.K. primarily by medical professionals. Despite the lack of scientific evidence supporting its effectiveness, FGC was often carried out as a medical treatment for various perceived medical and psychological conditions, including hysteria, “lesbianism,” and excessive masturbation. Another practice that should be considered a form of FGC is the “husband stitch.” The “husband stitch” refers to the practice of adding an extra stitch during the repair of a perineal tear or episiotomy after childbirth, ostensibly to tighten the vaginal opening for increased male sexual pleasure. Just this year, a lawsuit was filed in California against an OB-GYN who for decades allegedly performed FGC on patients. These practices were influenced by prevailing attitudes toward women’s sexuality and health of the time period, which included misconceptions about the female anatomy, a tendency to pathologize women’s sexual desires, and a patriarchal medical system that often prioritized male sexual pleasure and control over women’s bodily autonomy and well-being. Clitoridectomies fell out of popularity in the United States in the mid 1900’s, and by 1977 were no longer covered by insurance. At the federal level, however, FGC wasn’t prohibited until 1996. With the passage of a federal law it became illegal to perform FGC on a girl under the age of 18, or for the parent, caretaker, or guardian of a girl under the age of 18 to facilitate or consent to FGC being performed on her. Transporting a girl for the purpose of FGC became a punishable offense in the U.S. in 2013. Even after FGC stopped being a legally recognized medical practice, and Congress passed a federal law making it illegal to perform, there were still reports of FGC being performed by health professionals in secrecy. In fact, in 2018, a medical doctor in Michigan was charged with performing FGC on minor girls who had traveled to Michigan from other states to undergo the practice. It was then reported that Dr. Jumana Nagarwala was a part of a secret network of medical providers who performed FGC on hundreds of girls in the U.S. The case triggered significant legal and ethical discussions in the media, amongst anti-FGC advocates, and legislators, not only about FGC, but also about children’s rights and medical ethics. It was also reported that FGC was occurring in some white fundamentalist Christian communities. The persistence of FGC in these communities underscored the need for a broader societal reckoning with how cultural and religious beliefs intersect with human rights, even within demographics not typically associated with this issue. However, disappointment arose when the 2018 case was eventually dismissed on a technicality, relating to how the original law banning the practice was passed by Congress. This set back highlights the challenges in addressing FGC within the current legal frameworks. As a response, Congress passed the Strengthening the Opposition to Female Genital Mutilation Act of 2020, also known as the Stop FGM Act 2020, to ensure that FGC remained illegal to perform on a girl in the United States. Laws on FGC also vary at the state level. In Connecticut, for example, there are currently no state-level anti-FGC laws. The CT Coalition to End FGM/C, a survivor-led organization, has been working since 2020, advocating for the passage of laws that protect children from FGC and support survivors. Today, various efforts are being made to end FGC in the U.S. through education, advocacy, and community outreach programs. Educational initiatives aimed at informing healthcare providers, educators, and the general public about the harms of FGC and the legal implications of participating in or condoning the practice are being carried out by community-based organizations across the country. In the last 3 years, the Department of Justice, Office of Victims of Crime, funded several programs aimed at preventing and responding to FGC, including grants for community-based organizations and law enforcement training initiatives on the practice. Despite these efforts, significant challenges remain. One of the primary obstacles is the enforcement of the laws against FGC, as it can be difficult to detect or prove cases of the practice occurring. Additionally, there is resistance to ending the practice in some communities where FGC is seen as a social norm that must be done in the name of tradition, as a rite of passage, or due to it being an identity marker. Changing these deeply entrenched social norms requires sustained and sensitive engagement with community leaders and members from impacted communities. Survivors of FGC play a crucial role in the movement to end the practice. By sharing their stories, survivors help to humanize the issue and bring attention to the physical and psychological trauma caused by FGC. Their voices are powerful tools for advocacy and education, helping to shift public perception of the practice and inspire action against it. A large part of Sahiyo’s mission is working with survivors to share their stories and experiences, to inform communities, governments, and the public about the harms of FGC. These stories are critical in helping to enforce and create laws that address FGC because those who have gone through the practice have the most knowledge and understanding of why and how it should be prevented. If you want to learn more about Sahiyo’s work with survivors, listen to survivor stories here.

Four women who were pivotal to the movement to end female genital cutting

By Megan Maxwell The movement to end female genital cutting (FGC) has been in effect starting as far back as the latter half of the 19th century through the voices, writing, and research of women who have worked for the rights of women and girls. FGC is present in 92 countries. In honor of Women’s History Month, Sahiyo is honoring four women from Egypt, India, Senegal, and Austria who changed the world for women and girls. Nawal El Saadawi & her brutal honesty Nawal El Saadawi, a doctor, feminist and writer, who was born in a community outside of Cairo, Egypt, was a survivor of FGC. She campaigned against FGC and for the rights of women and girls throughout her life. She started by speaking out against her family’s preconceived notions about the trajectory of a girl’s life and then used her voice to condemn FGC and women’s rights abuses through her books. She wrote many books including The Hidden Face of Eve, a powerful account of brutality against women, and saw women live those realities detailed in the book within the communities in which she worked as a medical doctor. She was a crusader but her work was banned. She was imprisoned and suffered death threats. Through her work, she championed for the rights of girls and women globally for decades. She died on March 21st at 89 years old. Rehana Ghadially & All for Izzat In 1991, Rehana Ghadially wrote an article entitled All for Izzat in which she examined the prevalence of female genital cutting and its justification. For this article, she interviewed about 50 Bohra women and found the three most common reasons given for FGC: it is a religious obligation; it is a tradition; and it is done to curb a girl’s sexuality. Through these interviews, Ghadially revealed that the procedure of FGC was anything but symbolic. “The girl’s circumcision has been kept an absolute secret not only from outsiders but from the men of the community,” she said. Ghadially experienced FGC when she was very young. Her research allowed her to share with the world the reality of what Bohra girls and women go through as a result of FGC. Ndéye Maguette Diop & the Malicounda Bambara community The community of Malicounda Bambara in Senegal, West Africa, was substantially influenced by the Community Empowerment Program (CEP): a program established by Tostan that engages communities in their languages on themes of democracy, human rights (including female genital cutting), health, literacy, and project management skills. In July of 1997, the CEP empowered the women of Malicounda Bambara to announce the first-ever public declaration to abandon female genital cutting to the world. Ndéye Maguette Diop was the facilitator for the CEP in Malicounda Bambara. She guided them through the program, which is designed to not pass judgment on the practice, but simply to provide information regarding FGC and its health risks. Diop used theater, a traditional mode of African communication and arts, as a means to better facilitate the exchange of ideas. “The women didn’t have any knowledge of these rights beforehand and had never spoken of FGC between themselves,” Diop said. As the result of reenacting a play, these women started to talk about FGC frequently with Diop and she said they “decided to speak about the harmful consequences on women’s health caused by the practice with their ‘adoptive sisters’ [a component of the CEP], as well as with their husbands.” Thanks to Diop, the conversation on FGC was opened up to the women of Malicounda Bambara. They took it upon themselves to investigate within their community until they concluded that the practice should be abandoned. Fran Hosken & her ideas of global sisterhood In 1975, Fran Hosken began writing her newsletter, Women’s International Network News where she reported on the status of women and women’s rights around the globe. The tagline for her newsletter was, “All the news that is fit to print by, for & about women,” and it featured regular sections on Women and Development, Women and Health, Women and Violence, and Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). Every issue of her newsletter had a section on FGM, including names and addresses for her subscribers to get more information on activities surrounding FGC around the world. Hosken was an American feminist and writer, but she was very involved in the livelihoods of women and girls around the globe.Her newsletter became popular for its research into female genital cutting and she ended up writing The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females in 1979. In her book, she reports on the health facts, history, The World Health Organization’s Seminar in Khartoum, The Politics of FGM: a Conspiracy of Silence, Actions for Change, Statistics, Economic Facts, and case histories from several African and Asian Countries as well as the western world. Fran Hosken’s writing and research were extremely influential in the movement to end female genital cutting and continues to be in the modern movement.

Female Genital Cutting (FGC): Is it an Islamic Practice? (Part 2)

By Debangana Chatterjee Though often being referred to as an Islamic practice, Female Genital Cutting (FGC) precedes both Islam and Christianity. It is believed to have originated in the Pharaonic era of Egypt. Elizabeth Boyle, author of Female Genital Cutting: Cultural Conflict in the Global Community, mentions in the book that before the advent of Islam, Egyptians, who valued FGC (particularly infibulation), introduced a strong slave system and expanded it towards the adjacent geographic region. At the onset of Islam in the Egyptian controlled region, Islam asserted a stringent prohibition towards enslaving other Muslims. Hence, non-Muslim were continued to be used as slaves, and since FGC was done to these non-Muslim women slaves to increase their worth and value as slaves, FGC was by extension spread to other parts of Africa by the slave traders. This remains one of the driving factors behind the spread of FGC in Africa simultaneous to the rise of Islam. Despite FGC predating Islam, the myth of it being an Islamic practice persists due to the impressions of virginity and purity remaining closely associated with the religion’s values. There are ample reasons to challenge the unnecessary association of the practice with the Islamic culture. First, FGC was common among the Egyptian Coptic Christians and a number of Tanzanian Christian communities. In fact, FGC was also reportedly performed on Western women in the 1950s as a cure to nymphomania and depression according to L. Amede Obiora. Secondly, the practice is rife only among a limited number of Islamic practitioners of the world. Islam is the world’s second largest religion with approximately 1.6 billion followers of the religion consisting of 23.2 percent of the world population. On the other hand, there are around 200 million reported cases of FGC worldwide which includes non-Islamic people as well. Even if one takes these numbers as absolute, merely 12 percent (approx) of the entire Islamic population is affected by the practice. Thus, FGC does not necessarily qualify as an Islamic practice, considering most of the followers of the religion either nullify FGC or even remain oblivious to it. Third: the Holy Quran altogether stands in opposition to inflicting harm; going by that logic Islam cannot be supportive of FGC inflicting mental/physical harm of any sort onto women/girls. Despite the Prophet being explicit about sunna (tradition) on male genitals, FGC’s existence within Islam remains debatable. In many countries, Islamic traditions often remain debatable, including discussions on FGC. In the documentary The Cutting Tradition, an imam from the Harar region of Ethiopia is heard explaining how it already existed among various communities and the Prophet merely advised a sunna way of cutting where only the nicking of the clitoral prepuce is permitted. In the same documentary the Grand Mofti of Egypt, Fadilet Al-Mofti Ali Gomma repudiates any religious basis for FGM/C, though in 1994 a religious decree was issued in the country in favour of the practice stating it as an honourable deed for women. In fact, the decree, issued by one of Egypt’s prominent clerics Sheikh Gad el-Haqq, admittedly mentioned that FGC is not obligatory in Islam but should be followed due to the traditional rituals attached to it. Even in the Afar region of Ethiopia, religious leaders are seen invoking Islamic scripture and text to counter continuation of FGC among practicing community members. The practice came to South-East Asia in the 13th century, due to the advent of Islam in the region after the change in regime. The Shafi school of Sunni Islam in Indonesia and Malaysia considers FGC an Islamic practice, yet they are culturally influenced by the region where Yemen and Oman are situated, countries that have considerable FGC prevalence. At a time in the world when right-wing politics riles up with growing Islamophobia, it is important not to straightjacket Islam in order to avoid its unnecessary vilification and mindless demonization. Islam, as it grew, got entangled with cultural traditions in such a manner that it often looks inseparable. But a close and nuanced study of the matter opens it up for further scrutiny and leaves room for potential dialogic engagement with the communities practicing female genital cutting so that in time these communities will come to abandon it. Read Part 1 – What Islam says about Female Genital Cutting and how far are these texts invincible? More about Debangana Debangana is a doctoral scholar at the Centre for International Politics Organisation and Disarmament (CIPOD), Jawaharlal Nehru University. Through her research, she is trying to locate the existing Indian discourse surrounding the practices of FGM/C and Hijab into the frame of international politics. If you would like to connect with Debangana, you can reach her at debangana.1992@gmail.com.

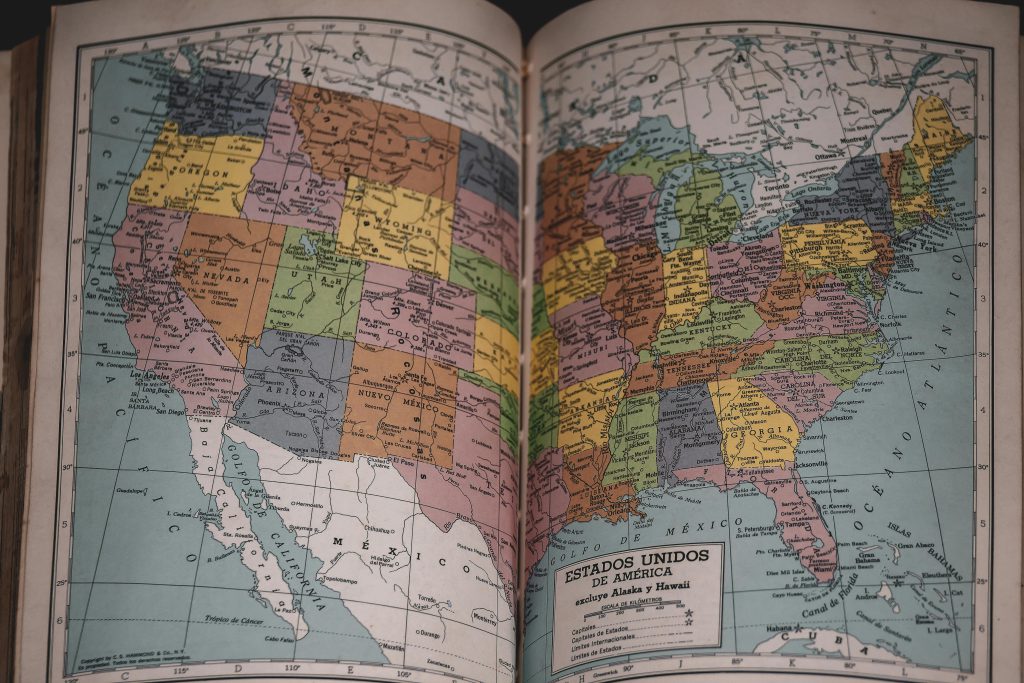

Tracing the Origins of Female Genital Cutting: How It All started

By Debangana Chatterjee Though the exact reason for the origin of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is unknown due to the dearth of conclusive evidences, multiple theories revolve around how the practice began. FGC precedes both the start of Islam and Christianity and is practised predominantly because of cultural traditions. FGC is not limited to a single community, religion or ethnicity. Rosemarie Skaine mentions that there are archival documentations indicating a Greek papyrus to have recorded women to get circumcised while receiving dowries around approximately 163 BC. In fact, there are several Greek scholars mentioning its prevalence before the advent of Christianity. Broadly, the practice is believed to have originated in Egypt where circumcised and infibulated mummies were found according to Frank P. Hosken. Gradually, it spread around the contiguous areas of the Red Sea coast among the tribes through the Arabian traders. In Hanny Lightfoot-Klein’s opinion, though the practice is believed to first have spread in the form of infibulation, clitoridectomy increasingly became the more acceptable form of FGC. During the Pharaonic era, the Egyptians believed in gods having bisexual features. Elizabeth Boyle recounts that these features were believed to reflect upon the mortals, with women’s clitoris representing the masculine soul and men’s prepuce that of the feminine soul. Thus, circumcision was considered to be a marker of womanhood and a way to detach from her masculine soul. As it became a socio-cultural norm, FGC became the utmost criteria for women’s marriage, inheritance of property and social acceptance in ancient Egypt. Lightfoot-Klein also suggests that population control was also one of the driving forces behind the practice as by controlling a woman’s sexuality; it kept the woman’s desires in check and made her sexually modest. Due to the narrowing of the vaginal orifice through infibulation, women would experience excruciating pain during sexual intercourse and thus, it becomes an effective measure to hinder premarital sex among women and ensure their fidelity. In fact, in places like Darfur, sudden desertification of arable lands made infibulation one of the population control measures. Boyle suggests the Egyptian practice of FGC and slavery can be correlated for providing an explanation of its origin. Before the advent of Islam, Egyptian rulers expanded their kingdom towards the southern region in search for slaves. As a result, Sudanic slaves were taken to Egypt and the areas nearby. Incidentally, slavery became commonplace with its aim to deliver servants and concubines to the Arabic world. As a result, women with stitched vaginas were in high demand due to the lessening possibilities that they would become impregnated. But after the arrival of Islam in the region, a strict prohibition towards enslaving other Muslims allowed the practice to get extended to other parts of Africa when the slave traders introduced infibulation among the non-Muslims to raise women’s value as slaves. This not only explains the introduction of FGC among North-African communities, but also explicates the coincidence of its spread in Africa simultaneous to the rise of Islam. In some cases, the practice has also sought its validation through Islamic scriptures. Doraine Lambelet Coleman says that one of the hadiths in Islam is thought to permit a limited form of cutting, though the hadith is also contested for being deficient of its genealogical authenticity. Despite the Prophet being explicit about sunna (tradition) on male genitals, FGC’s existence within Islam remains debatable. The practice was believed to be introduced in the South East Asian countries at around approximately 13th century, supposedly due to the reasons of Islamic conversion process after the change in regime. The predominant Shafi school of Sunni Islam in Indonesia and Malaysia justifies FGC as an Islamic practice and is culturally influenced by the Eastern part of the Arabian peninsula, the region where presently Yemen and Oman are situated. The justification for the practice in these countries come as they prescribe ‘nicking’ of the outer clitoral skin without really injuring the female genitals. In fact, this explains the burgeoning medicalisation of the practice in these two countries. In Singapore, the practice prevails due to the regional influence of Shafi Islam on the one hand and a few practicing ethnic Malay population on the other. The practice is rife among the Kuria, Kikiyu, Masai and Pokot people in Kenya, Zaramos in Tanzania, Dogon and Bambara people in Mali to name a few. Scholars have also indicated the income-generating facet of the practice in the face of unavailability of alternative livelihoods for the individual circumcisers. Though immigration due to slave exportation and other reasons is considered to be one of the predominant forces behind the spread of FGC in the West, L. Amede Obiora claims it was also reportedly performed on western women, especially in the United States, even in the 1950s as a cure to ‘unnatural female sexual behaviour’ that ranges from homosexuality, female masturbation to depression. References to ‘genital altercations’ in the Western countries are also not unfamiliar. In fact, Obiora also mentions that there are accounts of an English gynaecologist Isaac Baker Brown expressing his clear endorsement of such altercations in the early 1800s. To talk about India, the practice is prevalent among the Bohra community who came to the Western part of India from the North-African region as a trading community. The defenders of the practice in the community justify this as a stand-alone practice of khatna which, unlike other grave forms of it, only comes to denote removal of a pinch of clitoral skin bereft of its harmful effects. In this regard, often local circumcisers are being replaced by the medical professionals to highlight the hygienic conditions of its performance and gain greater legitimacy in its favour. On a whole, the practice has transformed and evolved dynamically since its origin. FGC through the course of its evolution came up with multiple facets and spread across cultures and geographic regions with various manifestations, meanings and narratives being attached to it. Tracing its origins, thus, not only helps in understanding its nuances but also minimises the tendency towards its

I was stripped of many things the day I was cut

(First published on January 23, 2016) by Mariya Ali Age: 32 Country: United Kingdom I have very few memories of my childhood, but one memory in particular stands out and haunts me to this day. Unfortunately, it’s a vivid, painful memory and fills me with anger when I recall it. I was five years old when my mother and aunt took my cousin and I on an “excursion”. I remember sitting in a car and approaching an unfamiliar block of apartments. I was confused; I didn’t know where I was and what I was doing there. Despite my seemingly endless young imagination, I could never have anticipated what happened to me next. I walked into a small apartment with a cramped living room at the end of a very short corridor. There was a dampness in the air and a slight smell from the poor ventilation. I approached the living room and sat on the floor. It was a warm day and I watched the net curtains of the large window slowly move with the breeze. I had been greeted by an old lady, whose face I can’t remember. I didn’t recognise her and was confused as to why I was currently in her apartment. I watched as she walked out of the room. I peered inquisitively into the kitchen and caught a glimpse of her heating a knife on the stove. I was always told to stay away from sharp knives at that age. Knives were dangerous. I could hurt myself. I remember the open flame on the stove and seeing the silver of the metal and the black handle of the knife while I watched her quickly hold it over the naked flame. She approached the living room with the knife in her hand, trying to conceal it behind her. She approached me. My mother asked me to remove my underwear. I remember saying no; I didn’t want a strange woman to see me without my underwear on. My mother assured me it would be okay; I trusted her and did as she asked. The old lady told me that she wanted to check something in my private area and asked me to open my legs. I was so young that I wasn’t scared at that time. I was confused, but not scared. I was innocently oblivious to how invasive and inappropriate this situation was and so I obediently did as I was told. I remember a sharp pain. An agonising pain. A pain that I can still vividly remember today. So intense that I still have a lump in my throat when I recall that moment. I instantly started sobbing, from pain, shock, confusion and fear. My next memory is that of blood. More blood than I had ever seen, suddenly gushing out from my most intimate area. I still didn’t comprehend what had just happened to me. I had believed that aunty when she had told me that she was checking something. I was young and naive enough to believe that people don’t lie and this was my first encounter when I realised that, unfortunately, the world doesn’t work like that. In so many ways I was stripped of many things on that day. My rosy outlook on life, my childhood innocence, my right to dictate what happens to my body and my faith in my mother not harming me. I continued to cry, the pain was excruciating and the sight of the blood traumatised me. I was given a sweet and comforted by my mother. The events after that are still hazy and my next clear memory is that of being back in the car and staring through teary eyes at the apartment building disappear as we drove away. Over the years I repressed this memory. There was no need to recall it. It was never spoken about and I still remained unaware of what transpired that day. A decade later, I was amongst some of my female friends. The topic of Female Genital Mutilation came up, or as I was to discover that day, “khatna”, a Bohra ritual performed on young girls. Hearing their recollections of what had happened to them, I finally realised that this is what had happened to me that day. I was mutilated. Thankfully for me, I had a lucky escape. The unskilled, uneducated woman who barbarically cut me did not cause me too much physical damage. Emotionally and mentally, there are many repercussions. I have a deep phobia of blood and a simmering resentment that my mother chose for this to happen to me. Although my mother believed that she was acting in my best interest, I struggle to come to terms with the fact that I was so barbarically violated. It may have been just a pinch of skin, but it was a part of me, a part of my femininity and a part of my womanhood.