The Climate Crisis & Human Rights

By Nesha Abiraj It is an understood global reality that women and girls are facing the harshest impacts of the climate crisis. Yet we seldom hear advocates at the frontlines of the climate crisis, speaking to the impact on human rights. Thankfully, this is changing. In January of 2023, I was invited by the North County Climate Change Alliance in California to present on climate justice and human rights. A few days prior to the presentation, the organizers asked if they could use my Sahiyo Voices Video from 2021 to introduce me as a speaker. Elated, I immediately said yes. On the day of the presentation, my colleague and fellow Climate Reality Leader, Justin Lowery, delivered my introduction. He clearly identified and articulated the connection I was aiming to make: the intersectionality between the climate crisis and the exacerbation of human rights violations, including female genital cutting (FGC), and by extension the need for international climate justice. People were beginning to understand just how much more was at stake, and I was hearing people speak about FGC and child marriage in spaces where I had not otherwise expected to hear it. This past year, after doing similar presentations, people came up to me expressing their shock and deep concern that these harmful practices even existed in the regions and/or communities they lived in. There were people learning about FGC for the first time, and some expressed a desire to learn more so that they could integrate this and other human rights violations into their work on the climate crisis. The UN Secretary General in his 2022 remarks stated that humanity now faces a “collective suicide pact” on account of the climate crisis. According to UNICEF, as the climate crisis pushes more children and families into extreme poverty, 9 million more children may suffer from wasting, the most life-threatening form of malnutrition by the end of 2022. We are now in 2023. More than 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone FGC and more than 400 million girls are now more vulnerable to this harm because of the climate crisis. UNICEF projects that one billion children are at extremely high risk due to the impacts of the climate crisis. In the face of such startling data, how can we not act? Since learning about the climate crisis through training to become a Climate Reality Leader with the Climate Reality Project, as well as continued research, I have integrated the impacts of the climate crisis in my work to promote the protection of women and girls from harmful practices such as FGC. Additionally, recognizing the need for international law and policy to provide a pathway for justice, accountability, and a deterrent to slow the pace of the climate crisis, I have also become an advocate for climate justice with Stop Ecocide International, specifically advocating for ecocide to become the 5th International Crime Against Peace. Simply put, laws geared towards environmental protection are woefully inadequate, and environmental crimes continue to occur at great costs to humanity because these crimes are treated with impunity. The people who are forced to bear the worst consequences of the climate crisis often come from vulnerable regions that are usually the lowest emitters of greenhouse gases. It is their lives that are being upended as a result of actions they had nothing to do with. That includes the women and girls who are now at a heightened risk of having FGC performed on them. The impact of the climate crisis on human rights and the urgent need for climate justice must be made central to any climate related policy. If we proceed as is without integrating these impacts, we run the risk of leaving millions of women and girls behind and at severe risk of harm. Women and girls are counting on us. You can help them by getting more involved in Sahiyo’s work as a volunteer or by signing on to Sahiyo’s petition to the United Nations. You can also support Sahiyo’s efforts by donating. These funds enable Sahiyo to support and train advocates, host educational webinars, and support survivors. In 2021 I was able to participate in the Voices project as an advocate at no cost to me. Two years later I continue to support making it possible for others to have the benefit of these educational and training opportunities at no cost. You too can do the same for someone else. Nesha Abiraj is an International Human Rights Lawyer. She is currently serving in her second year as an Ambassador to Island States and vulnerable coastal regions on International Climate Justice and Human Rights with Island Innovation. She also serves as an Ambassador to Stop Ecocide International, an organisation seeking to make ecocide, which is broadly understood to mean largescale and systematic destruction of nature, the 5th International Crime against Peace. Nesha also serves as a member of the US National Coalition to end early, forced and child marriages and is a US Advisory Board Member to Sahiyo. She previously worked with Human Rights Watch, Save the Children and continues to serve as a Lead Advocate for UNICEF USA on international humanitarian response relating to key poverty focused issues impacting the lives of children living in humanitarian and developmental settings including conflict zones. She is also a Climate Reality Leader and a member of the Commonwealth Lawyers Association.

Volunteer spotlight: Development Intern Shatize Pope

Shatize is a senior working towards her BA at Columbia University in New York. She is majoring in Human Rights with a specialisation in women’s studies and looking forward to attending NYU for law school to specialise in international law with the hopes of one day working for The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Shatize is very passionate about creating a safe space for women and young girls to be able to thrive in what is labelled a man’s world. She has been an advocate fighting for the elimination of female genital cutting (FGC) as it violates the human rights of women. As a mother to a young daughter, she is teaching her to always stand up for what is right no matter the obstacles that await. Shatize is looking forward to working for Sahiyo and educating those unfamiliar with the harm FGC causes millions of women and young girls daily. She strongly believes that we can put a stop to FGC and empower those who have been affected by it. What was your experience of learning about female genital cutting (FGC) for the first time? The first time I learned about female genital cutting (FGC), I was around 10 or 11 years old at a church retreat. There, I made a new friend from Africa who had just come to the United States; she was my age. I asked why she was here in the U.S. without her mom, and she began to explain that her family had sent her away so she didn’t end up like her older sister, who had died from being forced to undergo FGC. When I later asked my mom what FGC was, she told me it was a bad thing bad men do to girls and women. I looked it up for myself and was shocked to learn that a human would do such a thing to another human. From that day, I vowed a life of service to women and girls around the world. When and how did you first get involved with Sahiyo? I am currently studying Human Rights at Columbia University with a concentration in Women’s Studies. I began looking for an internship that focused on protecting women, and that is how I came across Sahiyo; I quickly knew this was the place for me. The work Sahiyo is doing to protect women and girls from FGC is what I have dedicated my life to, and I want to protectas many women and girls from this human rights violation. What does your work with Sahiyo involve? As a development intern, I, along with the other amazing interns, help draft grant proposals and conduct research on funding for the many different outreach programs Sahiyo has to support survivors of FGC. How has your involvement with Sahiyo impacted your life? My involvement with Sahiyo has reassured me that working towards the protection of women’s and girls’ human rights is my purpose in life. I have a daughter, and I want her to grow up in a world that values her, not a world where she is considered less than because of her anatomy. What words of wisdom would you like to share with others who may be interested in supporting Sahiyo and the movement against FGC? Sahiyo is giving a voice to the voiceless while bringing awareness to the harms being committed against women and girls. Supporting Sahiyo will allow a survivor to get help, tell their story, and help stop the practice of FGC. Human Rights are universal, and everyone has the right to protection; Sahiyo is creating a safe space for those who otherwise do not have it.

Aarefa Johari makes statement at Human Rights Council

On June 20th, Sahiyo co-founder Aarefa Johari submitted an online oral statement on Female Genital Cutting (FGC) in Asia at the United Nations’ 50th Human Rights Council. The statement was made on behalf of the Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW) and the Asia Network to End Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. The video statement was aired at an HRC “Interactive Dialogue session with the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.” It was one of over 75 video statements about health rights made by activists and experts from around the world. Johari’s statement highlighted the widespread prevalence of FGC in several Asian countries, and the lack of resources and attention towards addressing the issue in these nations. Johari called on UN member states to undertake thorough research on FGC in Asia, increase funding towards community-based organisations working to end the practice, and to enact legislation to prohibit all forms of FGC. You can view Johari’s video statement here.

Joanna Vergoth chosen as 2021 CRAVE Foundation for Women honoree

We are proud to announce that Sahiyo U.S. Advisory Board Member Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA, was chosen as a 2021 CRAVE Foundation for Women grant recipient. She is a psychotherapist, specializing in trauma and was choosen as a recipient for her committed activism of over 20 years in helping those impacted by Female Genital Cutting (FGC). The CRAVE Foundation for Women was established to support individuals working towards creating a world where pleasure is a universal human right. Read more about Joanna’s work here.

Who? A Zine About The Global Impact of FGC

By: Cate Cox In the fall of my junior year at university, I decided to take a course called “Human Rights and Global Literature.” In this class, we explored diverse kinds of literature that called into question different conceptions of human rights, including works by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Tadeusz Borowski, Vaddey Ratner, Farnoosh Moshiri, and Eka Kurniawan. When the professor announced that our final project was to create a Zine that explored a human rights issue important to us, I immediately knew what I wanted to do. According to the World Health Organization, female genital cutting (FGC) is a human rights violation and a severe form of violence against women and girls. After nearly two years of working with Sahiyo, I wanted my Zine to focus on FGC. A complex human rights issue that is often forgotten about in the United States, I hoped to create a Zine that would help raise awareness about FGC in America, and highlight the global prevalence of this form of gender-based violence. I decided to title my Zine Who? to reflect the many misconceptions that affect who we think FGC occurs to. I wanted to dismiss some of the misconceptions around FGC that assert it is only practiced in certain communities and in certain places. Given that my audience would mainly be my fellow classmates, I particularly wanted to focus on the prevalence of FGC in the United States. I included statistics such as the CDC estimate of women and girls affected by FGC in the U.S., and the many legislative delays in outlawing the practice. The hardest part of creating this Zine was deciding on what images I wanted to draw to accompany my writing. While working at Sahiyo, I have become increasingly aware of the ways in which violent and graphic imagery about FGC can re-traumatize survivors and stigmatize communities. Before I began to draw, I sat down with the Sahiyo Media Guide on Reporting on FGC; this was extremely helpful for thinking through the kinds of images I could draw to represent the harm FGC causes in a way that was also ethical and respectful to survivors’ experiences. After many edits and scrapped designs exploring the harms of FGC and who it occurs to, I still wasn’t quite satisfied. I explored the many consequences of FGC, and realized that I didn’t only want my Zine to highlight the harms of FGC. I wanted to provide my audience with ways to get involved in the world to end FGC and motivate people to become involved in the issue. I decided to end my Zine with a reminder that, while it may seem difficult, ending FGC is possible if we are all involved. The process of creating this Zine was a very enlightening experience that allowed me to think through both ethical reporting on this issue, as well as how to motivate people to become involved in the crucial work to end female genital cutting. Read Who? Female Genital Cutting (FGC) around the world.

Mutilation or enhancement: A researcher’s argument for respectful terminology on genital cutting

By Brian D. Earp I have published several papers on the ethics of medically unnecessary genital cutting practices affecting children of all sexes and genders. When my writing touches on the sub-set of these practices that affect persons with characteristically female sex-typed genitals, I have received some pushback for using the term female genital cutting (FGC) rather than female genital mutilation (FGM). An instance of such pushback came from a respected colleague in response to a paper of mine in Archives of Sexual Behavior, in which I argue against the use of ‘mutilation’ in certain contexts, as there is evidence that such stigmatizing language may have adverse effects on the very people who are meant to be helped. Given that this terminological issue is likely to keep coming up, I thought I would share parts of the reply I wrote to my colleague. I hope it can shed some light on at least one plausible way of thinking about such matters. My colleague argued that my use of ‘FGC’ rather than ‘FGM’ is disrespectful because it goes against the recommendation of the 2005 Bamako Declaration adopted by the Inter-African Committee (IAC) on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children. ——— On the matter of disrespect. I have had many conversations with women who consider themselves circumcised, rather than mutilated, and even if they agree that medically unnecessary genital cutting should not be performed on persons who are incapable of consenting, primarily children, they insist that it is harmful, stigmatizing, and paternalistic for others to simply define their own modified genitals as mutilated (a term that implies disfigurement or even an intent to cause harm). They explain that their loving parents, however misguided, did not intend to cause them net harm, just as, for example, Jewish parents who authorize that their sons be circumcised do not intend to harm them, but rather, take an action that is sincerely believed to appropriately integrate the child into an ancestral community. They recognize that, in their own communities, both male and female genital cutting practices are widely seen as improving the genitalia, including aesthetically, which is contrary to the very notion of mutilation. I may not agree with that interpretation myself, but it is not my position to tell these women (or their brothers) that their altered genitals are ugly or disfigured rather than, as they see it, aesthetically (or in some cases, culturally or religiously) improved. I will ask: Were these leaders democratically elected to express the considered opinions of their constituents, or were these leaders self-appointed? At the very least, they cannot have been authorized to speak on behalf of countless Southeast Asian or Middle Eastern women who have been affected by ritual forms of female genital cutting. In any event, I face a choice. I can disagree with the conclusion of these African leaders who seem to feel qualified to speak on behalf of millions of other women, including non-African women, and impose an entirely negative and stigmatizing interpretation of all of their altered genitalia regardless of how those women see their own bodies. Or I can show respect to those women who have shared their stories with me, as well as all the women in various reports and testimonies who have expressed strong objections to the term ‘mutilation’ being forced on them, and who would simply like to have the room to be able to evaluate and describe their own genitals as they see fit. One woman explained her feelings: “In my opinion, the word ‘mutilation’ used in reference to [what happened to me] is a degrading and disempowering term that strips women of their dignity and self-worth. Basically, it is a label that has the power to negatively influence one’s self-identity. If you understand labelling theory you will understand how damaging/influential a term or classification can be to an individual.” She continued with her experience: “Having just about survived my ordeal of forced body alteration I was very aware of the violation to my body. However, the introduction of the term ‘mutilation’ into my consciousness affected me mentally and physically. It made me view myself as an ugly, mutilated, and frowned-upon member of society. There started my journey of self-hate, which presented itself in many forms, including bulimia and social anxiety, to name but a few. To be called the ‘mutilated’ girl by health professionals stripped me of any dignity and covered me in shame on numerous occasions. Thankfully, I no longer see myself as a victim or survivor of ‘FGM’ – I refuse to allow that term to take away my power or to define who I am.” Faced with the choice between respectfully disagreeing with the analysis and conclusion of a group of leaders whose qualification to speak on behalf of others I do not know, versus showing respect to those women, such as the one quoted above, who have asked for the right to determine their own victim status (including whether they regard their genitals as mutilated or otherwise), I choose the latter. Referring to “the event” and “the torture” is using singular language to refer to a plurality of quite different events carried out in different ways by different groups for different reasons. As you know, the World Health Organization (WHO) uses the term FGM to refer to a dozen or more practices, ranging from nicking of the clitoral hood, which does not remove tissue. In many communities, for example in Malaysia, it’s often done by a doctor with sterile equipment and pain control, through to excision of the external clitoris with a rusty implement and no pain control followed by infibulation, as occurs in some rural parts of Northeast Africa, for example. It is entirely accurate to say that all of those quite different interventions are medically unnecessary acts of genital cutting; and I argue that all of them are morally impermissible if carried out on a non-consenting person. I have written about labiaplasty, a common procedure in Western countries. I

Women should not be harmed because of societal norms

By Sakshi Rajani Age: 17 Country: India Female genital cutting (FGC): the term sounded ruthless the first time I heard it. It was not long ago that I was introduced to this term. While going through my Instagram feed, I read a story about a law student who was spreading awareness about FGC, and I was clueless about what it was. Immediately I searched this issue online and learned how serious it was. Then, I pondered why I hadn’t known about it earlier. Why had no one around me talked about it? Upon researching it further, I came to know how deeply rooted this problem was in communities and cultures. My will to do something to end it became stronger. I looked for organisations working to end FGC and came across Sahiyo. I soon joined the organisation. The first time I spoke about FGC to my friends they said, “What is that?” I wasn’t surprised by their reaction because I, too, was unfamiliar with it. I asked them to research it on their own, and then I explained more about the harms. I told them the World Health Organization and the United Nations declared FGC a human rights violation. Then I introduced them to the groundbreaking Mumkin app created by two co-founders of Sahiyo, Priya Goswami and Aarefa Johari, where my friends could learn more valuable information about this issue. What are the hurdles in encouraging abandonment of or ending FGC? FGC is also often seen as a necessary ritual for initiation into womanhood and can be linked to cultural ideals of femininity, purity and modesty. A strong incentive to continue the practice is family pressure to adhere to conventional social norms. Women who break from this social norm can face condemnation, abuse and rejection from family or community members. Patriarchal society can help perpetuate it generation after generation. Female genital cutting should stop immediately, as a woman should have full rights over her body and no woman should be harmed because of societal norms and expectations. I am now an advocate to make sure FGC ends.

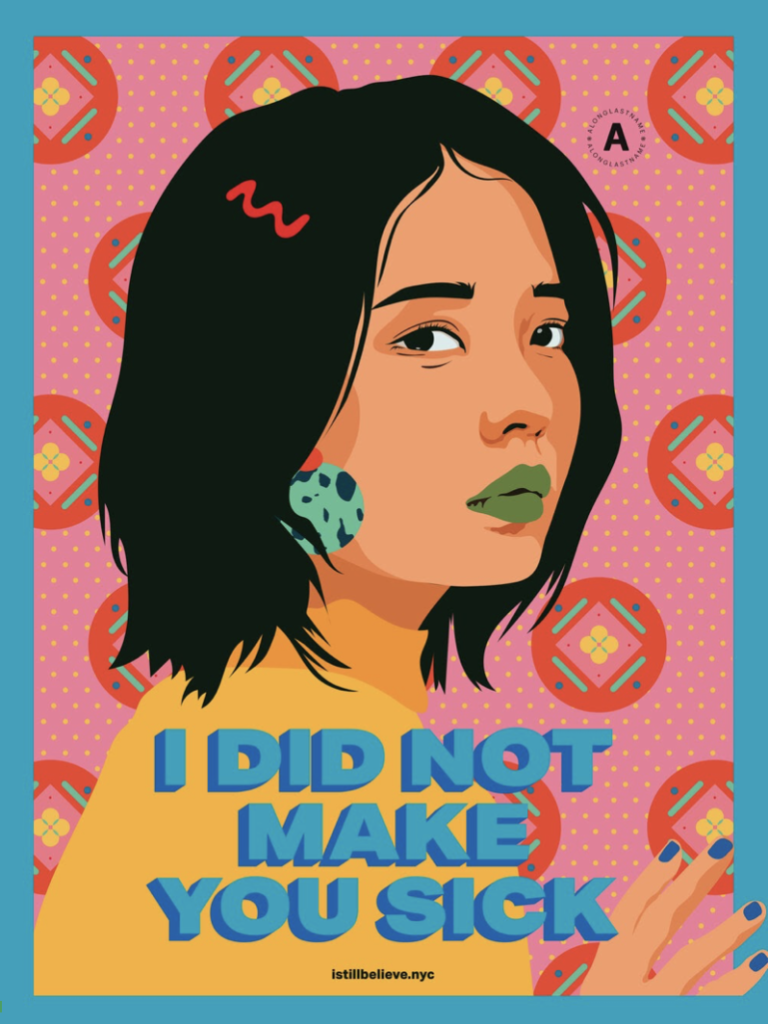

Sahiyo stands with AAPI communities experiencing racist violence

Sahiyo stands in solidarity with Asian communities and individuals who have been experiencing racism and hate crimes. We are an organization born from working with and supporting Asian communities. This violence concerns everyone and is of utmost importance to us, due to our proximity and connection to these communities. Sahiyo condemns the recent violence and rhetoric, along with the othering and oppressions Asians have faced in the United States since arriving. Over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, there has been a surge of hateful rhetoric and racist violence against the AAPI (Asian American/Pacific Islander) communities in the United States. By mid-March, the Stop AAPI Hate National Report logged over 3800 violent attacks toward Asian Americans, mostly women (68%). Attacks also targeted elderly people, and this abuse is unacceptable but unfortunately, not new, as evidenced here and here. The United States has a long history of oppressing and dehumanizing Asian Americans, from Chinese indentured labor to Japanese internment camps to the fetishization and Orientalism Asian women experience. This thoughtful opinion piece explains racism toward Asians in the United States, and what it says about our country. Take a moment to educate yourself about current and past harmful tropes forced on Asians and the context of anti-Asian racism in this country. This toolkit, as well as this one, aim to equip us all with the education and resources we need to Stop Asian Hate. It is also key to recognize this racialized othering for what it is–twisted with misogyny and leaving women concerned for their public safety. The racist attacks in Georgia, as well as other recent violent moments are filled with racism, but also sexism. Asian women find themselves in the frightening crosshairs of both forms of oppression. Thankfully, there are resources meant to support and protect Asian women. You can also check out powerful zine, Asian American Feminist Antibodies {care in the time of coronavirus}, a collaboration between the Asian American Feminist Collective and Bluestockings Bookstore, to hear Asian feminist voices speaking out. Trauma is inherited, and the suffering of some in the AAPI community can take a toll on all members. If you are struggling, check out this site focusing on AAPI mental health resources. What can you do? Call out ignorant jokes, hateful or micro-aggressive comments when you hear them. Learn how to interfere when you witness Asian-hate. This link contains a variety of options to register for Bystander Intervention to Stop Anti-Asian/American Harassment and Xenophobia workshops and training. Report any hate incidences you encounter here. Visit your local AAPI businesses. Restaurants, shops and other establishments have been hit economically in this wave of racism, so you can put your money into these businesses to support them and let them know they are valued and wanted in your community. Donate. Cover image credit: One of Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s panels for the “I Still Believe in Our City” public art series.

U.S. may deny asylum for females fleeing gender-based violence

By Hunter Kessous (Follow this link to take action immediately and stand with survivors before July 15th.) At the age of 17, Fauziya Kassindja narrowly escaped undergoing female genital cutting (FGC) and a forced marriage in her home country of Togo. She used a fake passport to make her way to the United States, and upon arriving at the border, explained to the officials that her document was fake and she was there to seek asylum. She was placed in a maximum security prison for nearly two years. Her case for refuge was initially denied, and was appealed to the highest immigration court in the U.S. where she was finally granted asylum. In 1996, Fauziya became the first to gain refuge in the U.S. on the grounds of escaping FGC. Her victory set the precedent for future immigrants to receive asylum from gender-based persecution. In addition to the precedent set by Kassindja’s case, there are multiple legal reasons why FGC qualifies as persecution. It violates multiple human rights documents, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child among others. To qualify for refugee status, an individual must prove the persecution they fear is for reason of her race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. FGC is often thought to be a religious requirement. It can also be argued that opposition to FGC is a political opinion. It seems obvious that FGC should be grounds for asylum in the U.S. Yet, women are still refused for reasons that are often untrue or impossible, such as “woman can refuse to be cut” or “the woman can relocate.” or “the woman can relocate.” Now, refuge for women escaping FGC may be significantly limited. A proposed rule by the Homeland Security Department and Executive Office for Immigration Review set to be finalized on July 15th, would radically restrict eligibility for asylum, especially for those fleeing gender-based violence (GBV) and for LBGTQIA+ individuals. The regulation bars evidence that supports an asylum claim if it could be seen as promoting cultural stereotypes. On this basis, a judge could refuse refugee status to a woman fleeing FGC because the judge may think it promotes a cultural stereotype. A woman escaping GBV could be denied asylum on the grounds that feminism is not a political opinion. It even allows officials to dismiss some asylum applications without a hearing. These are only a few examples of the many ways this rule would dismantle the U.S. asylum system. We must act now to protect women and girls. The rule will go into effect July 15th, but before it is finalized the government must read and respond to comments sent by organizations and individuals. To submit a comment, follow this link. A sample comment is provided, but it is imperative to make your comment unique in order to ensure that it is read and responded to accordingly. For more resources to fight the finalization of this harmful rule, read this document containing websites for action-taking, informative webinars and articles, and sign-on letters.

Understanding the Supreme Court’s latest judgement mentioning female genital cutting in India

On November 14, after a year of silence on the female genital mutilation/ cutting (FGM/C) case pending before it, the Supreme Court of India mentioned that the case will be referred to a seven-judge Constitution bench. It is likely that the case will now be heard in conjunction with three other petitions dealing with women’s rights and freedom of religion: cases about Hindu women’s entry into the Sabarimala temple, Muslim women’s entry into mosques, and the entry of Parsi women married to non-Parsis into fire temples. Previously, in its September 2018 order, the Court had referred the FGC case to a five-judge Constitution bench. Since then, the case had been pending. On November 14, however, the Supreme Court brought up the FGC case while hearing a batch of review petitions in the case about Kerala’s Sabarimala temple, where women of menstruating age were traditionally not allowed to enter. The review petitions challenged the Court’s 2018 order which lifted the ban on women’s entry into the temple. In its November 14 judgement, a five-judge Supreme Court ruled that the debate on women’s entry into the temple overlapped with other cases about gender and religious rights that are pending before the Court, including women’s entry into mosques and fire temples and female genital mutilation/cutting among Dawoodi Bohras. It stated that a larger bench first needs to rule on the interpretation of the very principles governing the fundamental right to freedom of religion in the Constitution, before passing judgement on all of those cases from different communities. The implications of clubbing these various cases under one umbrella are yet to be seen, but the Court’s judgement does raise some concerns. Although these cases share the common theme of women’s rights within religion, the cultural ritual of cutting minor girls’ genitals is very different in substance from the rules restricting women’s entry into places of worship. It would be ideal if each of these issues are evaluated separately, on a case-by-case basis. Sahiyo believes that the matter of FGC needs to be treated with a little more urgency. Fourteen months have already passed since the Supreme Court first referred the FGC case to a Constitution bench last year. That bench was never formed, and now the Court’s decision to first adjudicate on larger questions of law is likely to stall hearings that may have been scheduled in the FGC case. Since the practice of FGC involves causing bodily harm to young girls, every delay puts more girls at risk of being cut. A quick recap of the FGC case In April 2017, Delhi-based lawyer Sunita Tiwari filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court seeking a ban on the practice of female genital cutting (also known as khatna, khafz, sunnath or female circumcision) in India. FGC is practiced among the Dawoodi Bohras and other Bohra sects in India, as well as among certain Sunni Muslims in the state of Kerala. Tiwari’s PIL, however, refers only to FGC among the Dawoodi Bohras. After Tiwari’s PIL was admitted in the Court, other intervention petitions were also filed in the case, some supporting a ban on the ancient practice, and one party (the Dawoodi Bohra Women’s Association for Religious Freedom) defending FGC on the grounds that it is an essential religious practice for the Bohras. The Dawoodi Bohra Women’s Association demanded that the matter of FGC be heard by a Constitution bench since it was about the Constitutional right to religious freedom. The case was heard by a three-judge bench which observed during a hearing in July 2018, that the “bodily integrity of women” cannot be violated. However, in September 2018, the bench referred the case to a five-judge Constitution bench. This meant that the practice of cutting a girl’s genitals — which the United Nations classifies as a human rights violation — would now be scrutinised through the lens of religious freedom. In light of the latest Supreme Court judgement, this will continue to be the case, except that now a larger, seven-judge bench will first examine the interpretation of Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution pertaining to the right to religious freedom, before adjudicating on matters of FGC and women’s entry into places of worship. What the Court said: Majority and Minority judgements The Supreme Court’s judgement on November 14 was not unanimous. Three of the five judges on the bench delivered the majority judgement, in favour of referring the Sabarimala, FGC and other cases to a seven-judge Constitution bench. This 9-page majority judgement was authored by Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi. The other two judges (Justices Nariman and Chandrachud) authored an elaborate 68-page dissent, insisting that there was no merit to the review petitions in the Sabarimala case and that the other cases of FGC, mosque entry or fire temple entry should not be clubbed together with the Sabarimala issue. The majority judgement stated the following: “The issues arising in the pending cases regarding entry of Muslim Women in Durgah/Mosque;…of Parsi Women married to a non-Parsi in the Agyari;…and including the practice of female genital mutilation in Dawoodi Bohra community…may be overlapping and covered by the judgment under review. The prospect of the issues arising in those cases being referred to larger bench cannot be ruled out…The decision of a larger bench would put at rest recurring issues touching upon the rights flowing from Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution of India.” The majority judgement specified that the larger bench would essentially have to answer seven questions about the principles of Articles 25 and 26. These questions include these four points: What is the interplay between Constitutional freedom of religion and other rights granted in the Constitution, particularly the right to equality and prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of religion, sex, race, caste, etc? What exactly does “constitutional morality” mean? To what extent can the Court determine whether a practice is essential to a religion or a religious denomination? To what extent can the Court give judicial recognition to