My brain decides who I sleep with, not my clitoris

by Sabahat Jahan Age: 24Country: India I am sitting in a cafe and thinking about whether I would ever make my daughter go through the painful ritual of genital mutilation, the way my mother did it to me in the name of religion. I am 24 years old, studying journalism, a Muslim girl from a community that blindly follows Female Genital Mutilation even today. All my life I believed that FGM is good for my health, and that all the urinary problems I am facing are other unconnected problems. I didn’t realise that the bigger problem was that my clitoris was removed when I was seven. I don’t even remember how it was done, or whether it was painful for me. And I never gave it a thought because I trusted my mother when she said that it was good for my health. I don’t blame her but I do blame the ritual. Not many Muslim sects follow it but my community does. I first came to know about FGM when I read the work of author Ayaan Hirsi Ali. I then read about Sahiyo in the Hindustan Times. I was in a state of shock and I called my mother. With a calm mind, I asked her, “Maa, why did you do that to me?” She said, “Beta because it will control your sexual urges, you won’t sleep around and your virginity will be maintained.” I thought, so much for this virginity! Is this why I have to suffer from urinary problems from time to time? Sleeping with someone or not is my problem, my consent. It’s my brain that will decide, not my clitoris! I had no words to say to my mother, I just said “okay” and disconnected the call. I am not angry with her, she just followed what her culture and religion taught her. Yes, I do face problems when I make love. It is painful and it is problematic. The ritual didn’t stop my sexual urges but it made sex difficult for me. I am a literate person and I am standing against FGM. I will try my best to make people realize that it is wrong. I am thankful to Sahiyo for standing up and talking about it. I am glad the taboo around talking about it is removed and I can share my experience as a victim of FGM. (A version of this post was originally published on the blog Wanderlustbeau on February 23, 2017.) This post was later republished in Gujarati on March 6, 2018. Read the Gujarati version here.

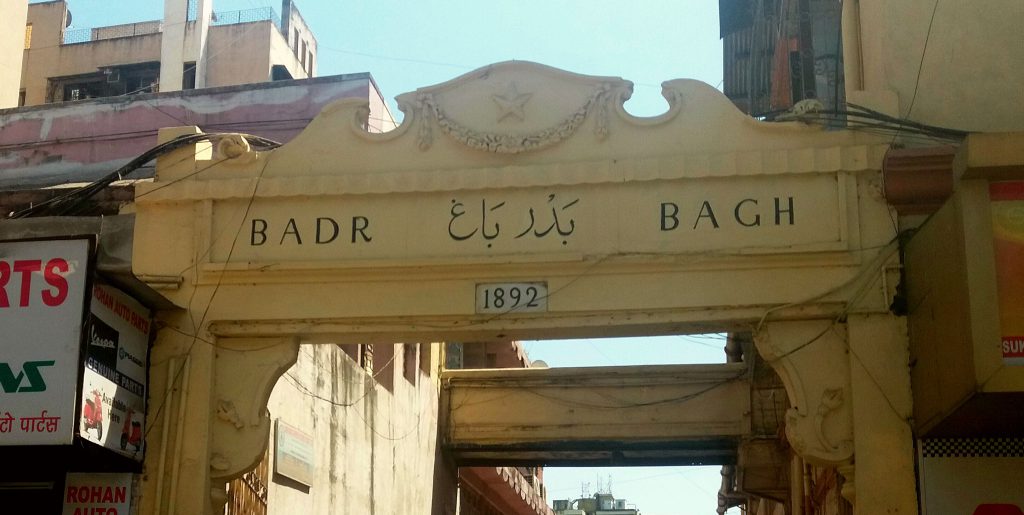

A conversation on Khatna with Suleimani Bohras

Is there only a little piece of flesh between ‘good’ and ‘bad’, asks a Suleimani Bohra

Female Genital Cutting exists to preserve patriarchy: A Bohra survivor speaks out

by Mubaraka MotiwalaAge: 18Country: India (This essay was first published on the Safe City blog on January 22, 2017) Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is the ritual removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. Ever wondered why it’s done? Well I did and I found out what a heinous act it truly is. In the summer of 2016, I went for a vacation and discovered that I too was a victim of FGM. This came as a complete shock to me; like a repressed memory it just zapped my brain and froze my memory. I was in the bus having a conversation with one of my Muslim female friends and in the midst of talking about religion she suddenly asked me if I was circumcised? At first I was confused and gave it a good thought but nothing came to me, so I said, “no, that wouldn’t have ever happened to me’’. Saying this, we continued with our conversation. A month later a few people in my community started talking about it and I had a few college classmates come up to me asking me to be a part of the FGM movement or if I’ve experienced it. This led me to really think about this and finally when I was travelling back home one day the memory came rushing in and completely baffled me. I am in fact a victim of this preposterous act and was so utterly unaware and uneducated about it. I was tricked into thinking that I’ll be getting chocolate and instead was taken to a shady-looking dimly lit house, where a lady was waiting for me and my grandmother. The lady asked me to lie down and spread my legs, which was an extremely strange thing for me to do. But my consent and opinion wasn’t taken into account, of course. She pulled my panties down and told me to stay still and that I won’t be hurt at all while my grandmother sat there, watching. And then it happened, she cut my clit and put some antiseptic but that didn’t stop me from crying out in pain and have a bruised vagina. Finally, I was given the promised chocolate and taken back home to forget and mask the day’s event completely. So my question is, why do we perform this practice? Through my research I’ve found out that FGM is practiced by people because it is often considered necessary for raising a girl, and to prepare her for adulthood and marriage. It is often motivated by beliefs that it is imperative to perform this. It aims to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity and in many communities believed to reduce a woman’s libido and therefore believed to help her resist extramarital sexual acts so she can be loyal to her husband. FGM is carried out because it is believed that being cut increases marriageability and is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are clean and beautiful after removal of body parts. Known as Khatna in certain communities, it is considered as a prestigious event and often celebrated and boosted by family members and society. But in reality I think this practice is performed in attempts to control women’s sexuality and ideas about purity, modesty and beauty. The reason behind all kinds of genital mutilation is to restrict female sexual experience. It is usually initiated and carried out by women itself who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to social exclusion and generate rebellious nature. And to my complete utter surprise no religious scripts prescribe the practice. Practitioners often believe the practice has religious support and is good for female health but there are no known health benefits. So the truth is that nobody knows why we practice FGM but because it is imposed on us as a religious responsibility and as our ticket to be accepted and be married, we go along with it. Everybody has been lying to us telling us that this is the right thing to do and beneficial for our future. This entire malpractice is existent to ensure and preserve patriarchy in societies. Us women are always controlled by someone or something for our entire life. This kind of behavior makes us give in and accept the stereotypes that are actually abusive and violating to us. We are manipulated into submission and are to do what someone else commands us. Aren’t we all the creation of god and told that he gives us everything for a reason, then why take away our will and consent to decide if we want this to happen to us or not. What gives anybody the right to take away the will to have their own opinion and purloin a part of someone’s body parts. What gives another person the right to enforce such unacceptable and abysmal rituals! We need to stand up for ourselves, ladies, and show people that we’re not empty vessels and we can’t be controlled to do whatever another pleases. We are human too. Say no to Female Genital Mutilation.

Sahiyo blog post wins a Laadli Media Award

A Bohra woman’s personal essay about her experience of Female Genital Cutting, published on Sahiyo’s blog last year, has won the prestigious Laadli Media Award for Gender Sensitivity 2015-16. The essay, titled ‘It was a part of me…part of my womanhood‘, won the award for Best Blog in the ‘Web-blogs’ category in the eighth edition of the Western region Laadli Awards, which celebrate gender sensitive advertising and journalism in India. The award ceremony was held at Ahmedabad’s Gujarati Sahitya Parishad on February 23, with prominent dancer and artiste Mallika Sarabhai as the chief guest. The winning essay describes the author’s memory of undergoing ‘Khatna’ and her struggle to come to terms with it. Read below the jury’s citation on her powerful narrative: [blockquote]The blog is a powerful and vivid account of a woman’s memory of female genital cutting. She speaks about the secrecy of the practice as well as the young age at which it happens. This story is among a handful stories that carefully look at female genital cutting among the Dawoodi Bohra community in India.[/blockquote] This essay was among the first few accounts of Bohra women willing to share their stories on Sahiyo’s blog when it launched in December 2015. Sahiyo believes in the power of storytelling and this blog is a story-sharing platform for all those who feel passionately about khatna or FGC and who wish to see the practice end. We would like to say a big thank you to Population First, the organiser of the Laadli Awards, for honouring Sahiyo’s blog contributor through this award!

Deen and Duniya (Religion and the World) a film by Alisha Bhagat

By Alisha Bhagat Country: United States & India I made Deen and Duniya in 2004 before my senior year in college. I received a Vira Heinz grant for women in leadership and thought it would be interesting to turn an anthropological lens on my own community – the Dawoodi Bohras. I am particularly interested in the role of women in the Bohra community and wanted to better understand certain dilemmas I saw while growing up in the community. When I sat down with people one-on-one while making this documentary, I found I was able to connect with them more and find out their logic for observing certain practices – be that science or faith. The film is intended for a wide audience both inside and outside the community. For non-Bohras I wanted to show the positive things about our community and the everyday joy that we experience in things like sports, prayer, communal meals and family. I also wanted to highlight some of the issues that all women in patriarchal societies face – control over women’s sexuality, bodily autonomy, and the dual burden of work and running a household. I did not set out to make a film about FGM but I knew from the beginning that it should be included. (To watch the video click here.) It is both a wonderful and frustrating time to be a Bohra woman. As the film highlights, we are given so many opportunities for achieving educational and career goals. We are quick to adopt new technology and want to live in the modern world. At the same time, we are often required to shoulder a greater burden than men. We have to work hard in our careers and also cook and clean and raise children. We have a lengthy Iddat (mourning) period that men don’t have, and are silenced from talking about the things happening to our bodies. I recall knowing from an early age that my father and brother were circumcised but it was only after I went to college that my mom revealed to me that she had been also. I found it so interesting that a practice so widespread was so taboo. Storytelling can be a powerful tool in creating social change. For example, a group of researchers in Sudan found that entertaining films can change attitudes and reduce gender bias. For those within the community, the purpose of the film is to start a conversation about why we observe certain practices. I’m proud that it can continue to do that. For years my parents used to show the film to every bohra guest that came over to our house (and I can assure you, that’s a lot). In the film we intentionally ask open-ended questions and the views of the interviewees are their own. Often after seeing the film, folks would share their own stories. My hope is that the film inspires you to do the same. The segment on FGM begins at the 19 min mark. However, it is recommended that the film be viewed in its entirety to understand the practice within its cultural context. Bio:Alisha Bhagat is passionate about sustainable development. She is a futurist, feminist, and avid gamer. She lives in New York with her husband, beloved daughter, and adorable kitty.

My daughter is the joy of my life. There was no way I could have her cut.

by Ashraf Engineer Age: 41Country: India Picture this if you can without your heart racing and eyes welling up. A girl, let’s say she’s seven years old, is dressed up by her mother and told she’s being taken for a walk and an ice cream. She clings to her mother’s arm in glee and follows her, secure and happy. She is led to a house in the neighborhood where her mother undresses her and holds her down. A strange woman removes a razor blade and in a single, heart-stopping motion cuts the child’s clitoral hood. The pain will ebb, the flowing blood will stanch but the scars will remain for life. A child has been damaged and her trust broken. I hail from the Dawoodi Bohra community where female genital cutting (FGC) is prevalent but the thought ofsubjecting my little girl to it never once entered my mind. She is the joy of my life, she gives it meaning. There was no wayI could do that to her. Among the many ugly manifestations of patriarchy, I believe FGC is perhaps the most horrific. We see everywhere how society feels the need to control every aspect of a woman’s life – from whether she can live aftershe is born and whether she can get an education to whom she can marry and when. This attitude often extends to controlling her sexuality – through FGC. FGC is one of the most serious human rights issues before us today. It is an ongoing practice rarely talked about even by those who have undergone it, and it is not part of the public consciousness. Like marital rape and abuse, it exists around us but is rarely thought about. According to UNICEF data, there are at least 200 million girls and women across 30 countries who have been cut. If they were to form a country, it would be the sixth most populous in the world. We are looking at an alarming crime against humanity that needs our urgent attention. FGC is illegal in many countries – a United Nations resolution against it was signed by 194 countries in 2012 – but its abandonment will require more than a law. Since the root of the problem is patriarchy, a social system in which males are all-powerful and wield great authority over women, men must become an integral part of the solution. FGC is perpetrated on women, but I believe it’s done to satisfy the male craving for control of female sexuality. Indeed, societies in which FGC is practiced tend to be dominated by men. It’s time for men to speak out against this harmful practice. It’s their duty, and their collective voice will matter. If they wish to, they can make a difference. Men need to stand up and be counted – primarily as fathers of girls in danger. This will help men too. Secure, happier women are necessary for stronger, fulfilling relationships and a progressive society. Here are a few steps that can be taken immediately by individuals and governments: Pass a law that criminalizes FGC in India. The movement against this practice is gaining momentum and it’s time for the government to act. Start a nationwide awareness and education initiative – targeting men especially – that underscores FGC’s psychological impact as well as the danger to societal health. Make awareness about FGC a part of sex education in schools. As the father of a young girl, even the thought of FGC creates a hollow feeling in the pit of my stomach. That such cruelty can be wreaked on anyone, let alone a child that has no clue of what is happening to her, breaks my heart. As a father, your primary instinct is to protect your daughter and help her grow. You can’t do that by mutilating her body and shattering her trust. (Ashraf Engineer, a former journalist, is a communication and marketing consultant. He recently released his first book, a Kindle-only release titled Bricks of Blood.) (Note from Sahiyo: As an individual, another immediate step you can take to help bring an end to FGC is to sign this petition by Sahiyo and 31 international organizations. Click here.)

Speak Out on FGM petition to the UN collects more than 500 signatures

In December 2015, Speak Out on FGM – a collective of Bohra khatna survivors – launched a signature petition on Change.org, appealing to various ministers in the Indian government to end Female Genital Cutting (khatna) in India. It was the first time that 17 Bohra women had publicly come out, as signatories, to speak against the practice, and the petition helped break the silence on Khatna both in the community and the media. Today, the petition has amassed more than 83,000 supporters. A year since this pioneering petition, on December 10, 2016, Speak Out on FGM launched a new petition on Change.org, this time addressed to the United Nations. The petition was launched on Human Rights Day – the last day of the global 16 Days of Activism campaign to end gender-based violence, and it has already received 544 supporters. The new petition reflects the growing, open support for the cause of ending khatna: this time, 32 Bohra women listed their names as signatories to the petition. This petition is an appeal by survivors of khatna, calling upon the United Nations to strengthen its recognition of India as one of the countries where FGC is practiced. While UN agencies do acknowledge that FGC is prevalent in “certain ethnic groups in Asian countries…in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka”, Indonesia is the only one of these countries that is included in the UN’s official FGC-prevalence statistic of 200 million girls cut in 30 countries. Girls cut in India are thus excluded from these statistics of global prevalence (learn more here). More global recognition of FGC would help spread awareness on the issue of khatna in India. More significantly, it would help Bohra women and men make official appeal to the Indian government to take policy-level steps to end FGC. Currently, there is no law against FGC in India, and the matter is still barely recognised as prevalent in the Indian Bohra community. Since the religious and administrative headquarters of the Bohras are located in Mumbai, and since India houses approximately half the international Bohra population of 1.5 to 2 million, ending khatna in India can go a long way in ending the practice among all Bohras. Through this petition, Speak Out on FGM hopes to speed up the process of instituting government and international mechanisms to highlight and promote measures to eradicate FGC. To sign the petition, click here.

As a psychotherapist, I would not recommend khatna

(This article was later published in Gujarati. Read the Gujarati version here.) by Anonymous Age: 36 Country: India I am a mental health professional and have been practicing counseling and therapy since 16 years. I learned about the practice of ‘khatna’ (Type I FGM) by chance, as my family spoke about the ceremony for a cousin of mine. I wanted to know more. I did not realize that I too had undergone it. I have no memories save a snapshot of me feeling a burning sensation and then being examined by my mom and grandmom. I grew up learning never to talk about this subject, as this was the haram boti that was removed from my body. I was told I was now pure. As I grew older and studied psychology, I came across an article that spoke about FGM, and suddenly I understood what had happened to me on that day. I was shaken but left with no choice but to accept it, as no one understood the impact of what had happened – not even my progressive parents. My life proceeded from then on no differently from that of other girls. My marital life, especially the sex, was unaffected. I was able to have a satisfactory sexual life and also orgasms, and largely I felt I was not affected by the khatna. Either that or I had repressed it so as to cope with the trauma that I may have undergone at the age of seven. I remember at childbirth, however, I had to undergo an episiotomy. According to a study cited by the UNFPA, women who had undergone genital cutting faced a greater risk of needing a Caesarean section, an episiotomy, and an extended hospital stay after childbirth, compared with uncut women. In peer supervision earlier this year, I processed what happened to me and dealt with it as a part of my life. I recognize in hindsight that there are effects of FGM. It scars the soul and you wonder if it is even required to be done. The procedure of khatna may cause lasting psychological stress. Among children, it could trigger disturbances in behaviour, often because of betrayal of trust by loved ones. Adult women could also develop anxiety and depression. As a mental health professional who understands all this, would I recommend khatna? No, I would not, as I find that at its core, it is a measure to control women’s sexuality. I would term it as intentional gender-based violence.

We must realise that there is an alternative to khatna

by Insia Jaliwala Age: 18 Country: India The experience of khatna, not only the actual act but the implications of the practice, was a gradual revelation for me. In the vague haze of childhood memories, that particular day stands out. I must have been around 6 or 7 years old. My parents told me I could miss school that day and were taking me out, I was obviously very ecstatic. I was taken to a ‘lady doctor’; a gynecologist who applied a red serum on my hand with a cotton bud and asked if it burned. It did. She then proceeded to do the same to my genitalia. I remember the moment when she told me to remove my pants and lie down on the bed. “It’ll be over in a minute,” she said while holding a scalpel in her hand. There wasn’t much bleeding and I don’t even remember the pain. What I do remember is an inhibiting confusion and fear. That day isn’t registered in my memory as a traumatic event, but a day I associate with a sense of loss. That day an important part of my womanhood was snatched away from me. That day my body was mutilated without my consent. The reality of the twisted practice struck me only a few years ago when I got into a conversation with my elder sister who told me about her experience, which was much worse and painful. After, I started to explore the subject more. I read about female circumcision and came across horrifying stories from Africa. I stumbled into many stories of khatna told by the women around me. I had started to understand the terrifying implications of the practice which differed from person to person and the physical and mental trauma some of my own sisters and close friends had to go through, and are still going through. I also came across many justifications for the practice, some from my family elders which went along the lines of, “This is done to curb a girl’s sexual desire so that she can put her mind to other things”, among many others. All of this left me with an overwhelming sense of betrayal. My family, my community, had failed me. As I dwelled into it more, I realized that this act of oppression had (as with any other social issue or phenomenon) multiple dimensions and was woven in a convoluted fabric of culture, custom, and tradition. Earlier this year, as a film project for college, I decided to make a documentary on Khatna. During my research for the film, I came across Sahiyo and was amazed by the fact that so many women were willing to share their stories on this platform. My initial thought when I decided to make the film was that no woman would want to talk about this on camera. To my surprise and glee, many women around me agreed to be a part of it. There are hundreds of women (and men) out there who want this barbaric practice to stop. There needs to be a discussion about this on a communal level and people of the community need to realise that they have an alternative, they can choose not to impose this upon their young ones.