Experiencing Sahiyo’s Activist Retreat in Mumbai

By Xenobia Country of Residence: India There are those who talk about change, and then there are those who do things and bring about the change. I would like to tell you about the time I decided to be a part of the Sahiyo’s Activist Retreat in Mumbai, and met such wonderful people who, in my eyes, were nothing short of superwomen. I cannot even begin to describe how amazing it is to meet like-minded people all driven by the same cause. It is honestly inexplicable. In today’s times, do you know what good, honest peer support feeling is like? Let me tell you: it was out of this world amazing! Did a couple of seemingly insignificant days change my life? Yes, they did. Prior to this event, was I feeling anxious and apprehensive about what it would turn out to be like? Oh, extremely. Was I nervous? Yes. Was I also curious about what would I take away from this retreat? Yes. Did I think it was going to be all about a bunch of women getting together to purely rebel against a cause? I will admit, yes. I knew about Sahiyo, and the cause that they are fighting for. I admired and respected them because I had been fighting for the same cause all my life, too, but silently. Many members of the Bohra community do not react well to independent thinkers, so it takes a lot of courage and true liberation to speak your mind on a public platform. Naturally, one ‘black sheep’ tends to have heard about the other. But immense respect for them aside, I was partly curious about what I would really learn here, and partly interested in what could be done to rightly channel the feelings I felt toward the people who endorse female genital mutilation (FGM). Needless to say, I couldn’t stop talking about this retreat when I returned home! There were some brilliant, fantastic people there from all walks of life, sharing their experiences, sharing their stories and how they heard of FGM, how it has impacted their lives, and what they are doing about it. Our co-hosts Insia and Aarefa were warm as ever, right from introductions and group bonding activities, to efficiently addressing counter arguments and introducing us to a world of relevant introspection, as opposed to traditional garish rebelling. There was also a talk given by a reputed gynaecologist, where we learned so many essential truths about the details of FGM that no one else talks about. So enlightening! It was as if there was a strange connection between all of us toward the end of the program. It’s not news that Bohras suffer from a major identity crisis anyway, considering most cultural aspects are borrowed from different parts of the world with no real roots anywhere. For someone who always found it hard to really fit in anywhere, it was as if I had found home at last. In spite of everyone at the retreat coming from such different backgrounds, locations and mindsets, it was really amazing. I, personally, have always felt very strongly about FGM/C and the concept of a random third person deciding what should be done with my body without my consent. But this experience and interaction has not only changed the way I see things, but has also made my resolve and conviction stronger – about fighting for every girl child out there, subjected to any such torture and abuse, until I have no life left in me, irrespective of how long it takes. For showing me how to efficiently channel all that I feel toward all forms of injustice done to women, and for this beautiful chapter of my life, I will be forever grateful to Sahiyo.

Locating female genital cutting through films and documentaries

By Debangana Chatterjee Though films and documentaries related to female genital cutting (FGC) promise to uphold the realities surrounding the subject, there are undeniable strings of subjective interpretations attached to them. Thus, rather than becoming ‘real’, these films and documentaries transpire as the reel portrayal of realities. Desert Flower, a 2009 German production is the most pertinent feature film on the subject based on Waris Dirie’s 1998 autobiographical account of the same name. In the realm of popular culture, the film relegates the practice of FGC being coterminous to infibulation, whereas infibulation is one of the most extreme variations of the four types of FGC, as has been classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Rather than providing the holistic imagery of the practice, this film portrays a partial picture of it. The documentaries on FGC are majorly driven for either anti-FGM awareness campaigns conducted by various international organizations, or for journalistic ventures of finding and documenting facts by renowned media houses from across the globe. Some of these major documentaries include Warrior Marks (1994), The Cut (2009), The Cutting Tradition (2009), ‘I Will Never Be Cut’: Kenyan Girls Fight Back against Genital Mutilation (2011), A Pinch of Skin (2012), The Cruel Cut – Female Genital Mutilation (2013), True Story – Female Genital Mutilation in Afar, Ethiopia (2013), Reversing Female Circumcision: The Cut that Heals (2015), The Cut: Exploring FGM (2017), Jaha’s Promise (2017), Cutting the Cut (2018). Another talked about documentary of 2018, Female Pleasure, though does not solely deal with FGC, features the renowned activist against FGC Leyla Hussain to shed light on the practice as a mode of controlling female sexuality. With the exception of A Pinch of Skin and Cutting the Cut that focuses on the particularities of the practice in India and Kenya, respectively, from an internal vantage point, others make cultural commentaries on the practice from the perspective of anti-FGM advocates. A Pinch of Skin Cutting the Cut was produced in 2018 under the aegis of The Health Channel in Kenya. Winnie Lubembe, a Kenyan herself, is the narrator, producer, and writer. With a special focus on the Maasai community of Kenya, the documentary presents both against and for narratives of the practice. On the one hand, it discusses the hazardous aspect of the practice. On the other, views supporting legalization of the practice are also presented, as it arguably promotes medicalization as well as cultural preservation. The non-alienation of the community and the need for complementing legal banning with adequate awareness programmes and cultural redressal are the two main takeaways of the documentary. It also highlights the political nuances operating through the legal state apparatus. A Pinch of Skin, on the other hand, is a 2012 Indian production directed by Priya Goswami. This can be designated as one of the maiden attempts to shed light upon the practice among the Bohra women in India. The maker, despite not belonging to the cultural community, makes honest attempts to put herself into the shoes of the believers, and thus, brings out voices both pro and against the practice. In fact, the naming of the documentary is indicative given that it does not merely portray the practice as ‘gruesome’ and ‘barbaric’. Rather it highlights the practice of nicking the tip of the prepuce of the clitoris, prevalent among the Bohras. Barring these two, representations through visuals of the cultural ‘other’ from an external vantage point appear to lack intricacies and layers. For example, The Cut: Exploring FGM, The Cruel Cut- Female Genital Mutilation, and The Cutting Tradition are produced respectively by Al-Jazeera, Channel4 and SafeHands for Mothers in collaboration with the International Federation of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (FIGO), respectively. The Cut, directed by American-journalist Linda May Kallestein, has also been funded by multiple Norwegian agencies. Most of these representations are located beyond the cultural purview and thus, lack empathy in their cultural portrayal. Though The Cruel Cut- Female Genital Mutilation and Jaha’s Promise feature Somali activist Leyla Hussein and Gambian activist Jaha Dukureh respectively, it is to be reminded that the onus ultimately lies at the hands of the creative teams of these documentaries. Even Jaha’s Promise uses one of the clips from Barack Obama’s speeches where he is referring to the practice as ‘barbaric’ which as a term is discredited for its blatant cultural insensitivity. It is problematic to assume that the mothers always put their daughters through the practice intentionally being fully aware of its consequences. Fatma Naib, the presenter of The Cut: Exploring FGM, an Eritrean immigrant to Sweden, showcases details of the state of the practice in Somalia and Kenya with substantial subtlety so far as it highlights campaigners against the practice from within these cultures. As a whole, it is not merely about the geographic positioning of the creative teams but about the outlook that they share while describing cultural specificities. Nuances and variations of the practice are not adequately showcased in many of these films. For example, out of all the countries with reported cases of FGC, African countries especially, Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, and Egypt are highlighted out of proportion. It is largely because of the rampant prevalence of the practice mainly in these countries. It is to note that only 10 percent of reported cases worldwide are the most severe and may fall into the category of infibulation- even in Africa. Notwithstanding the need to highlight the regions with a higher percentage of the practice, these documentaries seem to make convenient choices so far as the cases are concerned. This comes hand in hand with exoticization of pain. For instance, the documentary True Story – Female Genital Mutilation in Afar, Ethiopia, starts with the representative audio of excruciating scream of a newly-wed girl who dies out of profuse bleeding due to forced penetration of her infibulated vagina. This scream is followed by figurative graphics of a splash of blood accompanied by a heart-wrenching narration of the incident. The Cutting Tradition with its explicit emphasis on four African countries including Egypt, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Burkina Faso,

Why female genital cutting still continues: Exploring the reasons behind its sustenance

By Debangana Chatterjee The reasons why female genital cutting (FGC) continues are multifarious and overlapping. Complex and interconnected sets of reasons for FGC are woven into the faiths of the communities. Thus, faith becomes the genesis of these reasons, making FGC considered to be beneficial by the communities. These reasons can be broadly grouped as traditional, socio-cultural, sexual and hygienic, but are also closely connected with each other: • Traditional: According to Anika Rahman and Nahid Toubia, authors of Female Genital Mutilation: A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide, for a number of communities FGC is considered a rite of passage to womanhood and is driven by traditional beliefs. This womanhood is often believed to add to the marriageability of the circumcised women. The practice is carried forward by the women belonging to these communities for generations. Though there is no direct mention of the practice in the Quran, hadiths became a traditional source of its justification. At this juncture of faith, tradition paves the way for the socio-cultural reasons behind the practice. Dogon people of Mali / Photo by Jenny Cordle • Socio-Cultural: Among practicing communities, the practice in many ways becomes a hallmark of communal identification, as it garners acceptability and induces social conformity within communities. Some communities are also believed to have adopted FGC due to contiguous cultural influences. Considerable communal pressure for performing FGC involves the threat of social ostracism. Local structures of authoritative forces ensure the continuation of the practice by implementing these measures on the basis of their social norms. As the practice remains one of the sole sources of income for traditional cutters, economic reasons as a corollary to the socio-cultural ones also drive the practice. • Sexual: FGC is believed to control women’s sexual behaviour. There are claims of it restricting women’s sexual urges. Extreme procedures, such as infibulation, are used as mechanisms to keep women’s premarital virginity and marital fidelity in check. Due to the extreme pain that intercourse typically causes in infibulated women, women do not get sexual pleasure. FGC is frequently claimed to be used as an impediment toward the “promiscuous” nature of women. • Hygienic: Many believe the removal of a part of female genitalia amounts to cleanliness. In this regard, cleanliness in the hygienic sense results in physical purity, which is ultimately believed to pave the way for spiritual purity. This understanding of purity becomes closely entangled with the cultural beliefs of femininity and modesty. Despite creating this broad rubric of prominent reasons, the reasons noticeably overlap and are distinct in manifestation when it comes to the customs of specific communities. In certain cases, there are multiple driving factors, whereas in other cases the manifestations of these reasons are even more particularistic. For example, as Laurenti Magesa, the author of African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life, explains among the Kikiyu people of Kenya, FGC is celebrated as a mark of womanhood. Among the Bambuti and Thonga community, during the procedure girls are shown no mercy and are treated with ruthlessness as a sign of their gallantry and bravery. Among certain groups in Tanzania and Somaliland, infibulation is believed to form a “chastity belt” around the skin of female genitalia. Magesa underlines a few reasons for FGC specific to diverse African communities. Primarily, it is conceived as a mark of valour and of enduring physical pain within the community. This pain is thought to teach girls about sacrifice for the community as well as a sense of belonging. Finally, many believe that the practice strengthens the community bond among generations and knits the community together. Among many communities, girls are prepared for the practice through an initiation ceremony. But among the Zaramo people of Tanzania, the girl is secluded for a substantial period after circumcision. During this particular period, girls are trained and informed about obedience in general, conformity to social norms, fertility, and childbirth. According to Kouba and Muasher, the Dogon and Bambara people of Mali believe that a child, born with both male and female souls, is also possessed by wanzo. Wanzo is believed to be evil residing in both the male and female genitalia and thus, cutting as a process helps in getting rid of wanzo. In India, Bohra Muslims are evidentially the most significant community practicing FGC, which is termed as khafz. As per the believers of the community, Da’i al-Mutlaq, also known as Da’i, hold an authoritative, infallible status in the community. Da’i or Syedna (as referred to by the Dawoodi Bohras) is considered to be the sovereign leader, spiritual guardian and temporal guide of the community. As Da’i considers Daim-ul-Islam as the binding religious text for the Bohras, diktats of the text are taken as truth by the community members. It is a text written by Al-Qadi al-Nu’man who served from the 11th to the 14th Imam of the Shia lineage. In this text, the Prophet is believed to advise for a simple cut of women’s clitoral skin as this assigns purity on women and may make them more “beloved by their husbands”. The community mostly puts forward religious reasons based on their faiths in support of the practice. There are multiple narratives justifying the practice among the Bohra community members. A substantial number of community members believe that the practice tames women’s sexual urges and preserves modesty. Many claim that the nicking of the prepuce helps increase women’s sexual pleasure by exposing the tip of the clitoral hood. In this regard, it is often put forward in the same breath as the genital altercation procedures of clitoral un-hooding. Similar narratives espouse that the practice induces purity among women. For them, if it is well within the rights of Muslim men to be spiritually pure by performing circumcision, it is unjustifiable to prevent women from attaining equivalent purity. In fact, in certain cases, there are convictions by the pro-FGC Bohras toward the futuristic scientific revelations about khafz’s perceived benefits. When faith becomes a part of people’s everyday life, life needs

The Legal Side of Khatna or Female Genital Cutting

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography and writing. She is currently conducting research on the individual experience of khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series: Khatna Research in Mumbai. Female Genital Cutting or khatna or khafz, as it is also called in the Bohra community, involves cutting or removal of the external female genitalia. Khatna has no known health benefits, but does have well-documented complications, which range from severe pain, excessive bleeding, and scar tissue to frequent infections. The movement against khatna in India perhaps began in the early 1990s with Rehana Ghadially’s paper, “All for Izzat”, which attempted to identify the key reasons for why khatna was performed in India. However, the movement only gained momentum in 2011, when the first online petition was filed against it anonymously. The online campaign triggered a barrage of women coming forward with their own stories of trauma caused by khatna. It further fueled both online petitions as well as an onground movement. Within the Indian context of the Dawoodi Bohra community, the majority of the cases of khatna constitute Type 1, also referred to as clitoridectomy, which involves either partial or full removal of the clitoris, or the fold of skin known as the prepuce, covering it. Interestingly, there are many men and women who support khatna. From a psychological viewpoint, it may be rooted in the cognitive dissonance theory. Men and women of the Dawoodi Bohra community have been indoctrinated to believe that khatna is an essential religious obligation, and the will of God is not to be questioned. The online campaigns provide women in the Bohra community an alternative narrative, which may be in direct conflict with their existing beliefs. This conflict has created a lot of anxiety and conversations which have led to the movement gathering momentum, eventually catching the attention of the Indian government. The uphill legal battle saw the government oscillating between supporting and opposing the movement. In May of 2017, the Ministry of Women and Child Development declared full support for survivors, deeming the practice a criminal offence with prosecution possible under the guidelines of POCSO (2012). The ministry requested the community to voluntarily take action to stop it. If it failed, the government would seek to implement a law to end it. In December of 2017, the ministry withdrew from its position, citing lack of empirical evidence despite proof from Sahiyo’s landmark study, which revealed that 80% of Bohra women globally have undergone khatna. Although the rejection from the government was disheartening, the momentum of the movement has not faltered. Organizations such as Sahiyo and WeSpeakOut continue to provide crucial support for survivors to rally in solidarity. Several countries in Africa, as well as the United States and Australia, have made consistent and successful attempts to end female genital cutting. To understand how this has been possible, we must examine how the socio-economic structure of these countries has played an integral role in their success. Several of these countries may have high literacy rates, greater awareness of their rights and a more conducive environment for survivors to speak out. The Bohra community aspect is crucial to understanding the Indian government’s hesitancy to pass a law. Although India is a signatory to several of the United Nations and World Health Organization conventions which view khatna as a human rights violation, it comes under the purview of existing Indian legislation, such as article 319 and 320 of the IPC and POCSO. No separate law has been passed against FGC until now. Things looked hopeful when the PIL filed against FGM/C was to be heard by the five-judge bench in the India Supreme Court. The decision initially seemed to swing in favor of banning the practice, as the judges referred to it as a violation of the rights of the girl child. The judges questioned how the violation of the “bodily integrity” of the child could be an essential practice of a religion, asserting that right to religious freedom does not negate other fundamental rights of the individual. Despite overwhelming support, the judges later backtracked, deferring to a constitutional bench to decide on the matters of religious rights and freedom. It was the most crushing setback for the movement. Initially, I wondered what the hesitancy was in declaring khatna as a human rights violation. Later, I realized that the hesitancy was due to the political context and not the practice itself. Family and religion are the founding threads of our Indian community, and khatna is so intricately woven within these threads. Family and religion are our sources of identity, and since India is a collectivist society our ideas, beliefs in practices such as khatna are rooted in a collective experience, rather than an individual’s. Thus, attempting to end khatna risks unraveling the whole moral power structure of the country. Initially, it will begin with the Bohra community, but it may create a ripple effect across the country within other communities and religions. The moral thread of India is religion, and religion dictates our gender roles. If khatna is being questioned, we are unraveling this power structure by questioning the clergy’s teachings, and instead seeking the truth for ourselves by reading the religious scriptures whose access has unduly only been given to men for so long. Perhaps, with this newfound knowledge, our perception of the world will shift, leading to a destabilization of the existing structure and establishment of a new order with women in power. Change is just around the corner. Although the law is the first concrete step toward ending khatna, it is also a double-edged sword with unintended consequences. The law has the potential to push the practice further underground. The more discreetly cutting is done, the more difficult it would become to track it. Furthermore, the law would bring into question the perpetrators of the crime. Is it parents, midwives,

Examining Female Genital Cutting and Intersectionality

By a Bohra The recent dropping of charges against Dr. Jumana Nagarwala, who is accused of performing female genital cutting on underage girls in the United States, on a constitutional technicality rather than perceived criminality, solidified my thinking about the relationship between power and oppression. This thought was first introduced to me by Irfan Engineer, the son of Asghar Ali Engineer, a prominent activist who engaged in a decades-long battle with the Bohra orthodoxy over community reform. Irfan, a successful activist in his own right, described to me the relationship between the Indian state and the Bohra clergy. As long as the clergy declared electoral allegiance to the government, the state would turn a blind eye to the clergy’s authoritarian rule over the Bohra community. This relationship was made visible by the government’s reversal of its support for a national law against FGC, shortly after Prime Minister Modi (dis)graced the stage at one of this year’s Bohra Ashura sermons. Modi extolled the virtues of the economically and educationally advanced Bohras, who were allegedly setting a great example for their impoverished and persecuted Muslim countrymen. Seeing Modi on stage, Bohra Muslims could almost forget the carnage inflicted in Gujarat in 2002, and Modi’s rampant Islamophobia since. The Bohra community has probably been shielded from Islamophobic violence because of the clergy’s close relationship with the ruling right-wing BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) and its ideological parent, the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh). Even I was willing to overlook the fact that the Indian government’s attempt at criminalising FGC was based more on criminalising Muslims rather than empowering women. Yet, I thought, maybe the ends will justify the means. I was wrong. Modi’s relationship with the Bohra clergy makes it clear that we cannot rely on the Indian government to end FGC in our community. Even if the Supreme Court rules in favour of criminalising FGC, we can be certain that the government will do nothing to enforce the ruling. This violent relationship between the state and vulnerable women is not restricted to the Indian context. I am reminded of the first FGC case to be prosecuted in Australia, where three people were sent to jail after being proven guilty. An appeals court, however, acquitted them all after new evidence was released that showed that “the tip of the clitoris was still visible in each girl”. The reduction of the emotional, physical and ideological violence of FGC down to a visual assessment of a pinch of skin shows the weakness of even Western legal systems in protecting marginalised women. It is similar to the victim blaming that is still a routine in rape trials, and the inability of the state to protect women who report honour-based violence. Whether through negligence or structural misogyny, Western and non-Western governments have failed women. If the government is not an ally, could I turn instead to ‘reformists’ within my own community? I am in contact with certain Bohras who are not part of the mainstream community, and reject the leadership of the current clergy. They believe that the current leaders have deviated from the true message of the Imams, and that we must educate ourselves by going back to the original sources of our tradition. I thought that this group of people (mostly men), espousing rationality and critical inquiry, would immediately be against FGC. I was wrong. The emphasis on going back to the original sources means that they accept, uncritically, the infamous book by Qadi Numan (Da’im Al Islam) that advocates for girls to be ‘circumcised’ once they are older than 7 years old. Any debate, often started by the few women in the WhatsApp group, about the necessity of this practice in our modern context, or even about the issue of consent, is shut down. I thought that a shared experience of living under a tyrannical religious clergy might force these men to be more critical of existing power structures and hear the voices of marginalised women. Once again, I was wrong. I learned that the patriarchy, embodied by these ‘reformist’ men, can never be leveraged to end violence against women. I learned that it is not worth compromising my core values in order to ally with fickle powers that do not center marginalised voices and their struggles. Real change can only happen from the ground up. This is why the work done by organisations such as Sahiyo is vital. By reaching out to individuals, and creating a space to share our stories, Sahiyo creates sustainable change within the community, and rebalances the power structures that exist within.

બધા નુક્શાનો શારીરિક નથી હોતા અને દરેક ધર્મ સંપૂર્ણ રીતે નૈતિક નથી હોતો

(This essay was originally published in English on September 21, 2018. Read the English version here.) લેખક : ઝીનોબીયા ઉંમર : 27 વર્ષ દેશ : ભારત આજે સોશિયલ મીડિયા પર અન્ય બાબતોની સાથે-સાથે મહિલાઓને સશક્ત કરવા, પોતાનો નિર્ણય પોતે જ લેવા, વ્યક્તિની ગોપનીયતાના અને તેના શરીરના ઉલ્લંઘન વિષે અને સંમતિની ભૂમિકા વિષેના વિચારો અને અભિપ્રાયો સાથે ગુસ્સો વ્યક્ત થતો જોવા મળે છે.અમુક લોકો એવી વાતો કરે છે કે બળાત્કારીઓને ફાંસી દઈ દેવી જોઈએ છે તો અમુક લોકો જાતિય છેડછાડ અને મહિલાઓની છેડતી કરતા લોકોને સજા કરવા વિષેપણ વાતો કરી રહ્યાં છે જેથી, જમીની સ્તર પર યોગ્ય પગલાં લઈ શકાય અને આવા લોકો છોકરીઓને પરેશાન કરતા પહેલાં બે વાર વિચાર કરે. પરંતુ, જ્યારે એક 7 વર્ષની અસહાય છોકરીનો બીજું કોઈ નહિં પણ તેમનું પોતાનું કુટુંબ અને સમાજ ગેરલાભ ઉઠાવે ત્યારે શું થાય છે? તેના માટે કોણ જવાબદારી લે છે?હું અહીં મારી પોતાની તકલીફો રજૂ કરવા નથી ઈચ્છતી પરંતુ, તમારી માહિતી માટે થોડી મૂળભૂત હકીકતો રજૂ કરવા ઈચ્છું છું. હું ભારતમાં મોટી થયેલી એક બોહરા મુસ્લિમ છું. જ્યારે વિશ્વ આપણને શાંત, શાંતિપ્રિય, વ્યવસાયમાં સમૃદ્ધ એવો સમાજ માને છે ત્યારે આપણે 6-7 વર્ષની નાનકડી છોકરીના અંગછેદનની એક ગુપ્ત પરંપરાને અનુસરીએ છીએ, જેને આપણે ખતના કહીએ છીએ. આ પ્રથા પુરુષો માટે કેવી રીતે આરોગ્યની દ્રષ્ટિએ “જરૂરી” છે અને અંતે, તે તેમના સેક્સ જીવનમાં મદદરૂપ થાય છે તે વિષેની ઘણી દલીલો કરવામાં આવે છે પરંતુ, અધિકાંશ શિક્ષિત અને સંસ્કારી લોકો એ બાબત સાથે સહમત છે કે આ પ્રથા એક બૈરીના શરીરિક, માનસીક અને ભાવનાત્મક આરોગ્ય માટે નુક્શાનદાયક છે, ખાસ કરીને એટલા માટે કે તેના પર કોઈ દેખરેખ રાખવામાં આવતી નથી અથવા અધિકાંશ આવી પ્રક્રિયાઓ બૅસમેન્ટોમાં એક અશિક્ષિત બૈરી દ્વારા કરવામાં આવે છે.આ પ્રથાને વિશ્વના અન્ય પ્રદેશોમાં આધિકારીક રીતે “ફીમેલ જેનિટલ મ્યૂટિલેશન (એફજીએમ)” કહેવામાં આવે છે અને તેને અસહાય છોકરીઓ પર થતા અપરાધ તરીકે માનવામાં આવે છે. શા માટે? શું કારણ છે? અમુક લોકો પવિત્રતા વિષે તો, અમુક લોકો પિતૃપ્રધાનતા વિષે વાત કરે છે. અમુક લોકો તેને એક આદેશરૂપ પરંપરા હોવાને કારણે માને છે અને જો એક મૌલા તેને ફરજિયાત કહે તો તેને નામંજૂર કરવાની હિંમત કોણ કરે? અમુક લોકો દબાણને વશ થઈને માને છે તો, અમુક લોકો બ્લૅકલિસ્ટ થવા અથવા વીરોધીનું લૅબલ લાગવાના ડરથી માને છે.જે લોકો ઉત્તર માગે છે તેમના માટે એવો પ્રચલિત જવાબ આપવામાં આવે છે કે તે એક બૈરીની જાતિય ઈચ્છાઓને નિયંત્રણમાં અથવા અંકુશમાં રાખવા માટે કરવામાં આવે છે. એ બાબત સાચી હોય શકે કેજ્યારે આપણે રણોમાં અને સમૂહ (ટ્રાઈબ્સ)માં રહેતા હતા અને લોકો હંમેશા અન્ય વ્યક્તિની બૈરીને ઉપાડી જવા માટે આતુર રહેતા હતા તેવા યુગમાં, કદાચ આ પ્રથા મદદરૂપ થઈ હશે. આજે કોઈપણ કારણ હોય તો પણ, શું તેનો કોઈ અર્થ છે ખરો? તમારો ઉદ્દેશસારોહોય તો પણ,એક બૈરીની સંમતિ વિના તેણીના શરીર સાથે શું કરવું એ નક્કી કરવાનો તમને કોઈ અધિકાર નથી.તમે કોઈપણ હો, તમારો ઉદ્દેશ કોઈપણ હોય તો પણ, નુક્શાન થયું છે અને તમે કોઈ ગુનેગારથી ઓછા નથી. પિડીતો માટે તેનો અર્થ શું છે? આપણા દ્વારા અનુસરવામાં આવતી પ્રથા આક્ષેપ અનુસાર ‘ટાઈપ 1’ પ્રકારની છે અને તે આફ્રિકન સમુદાયો દ્વારા અનુસરવામાં આવતી ‘ટાઈપ 2’ અને ‘ટાઈપ 3’ થી (ગંભીરતાના સ્તરના આધારે) અલગ છે.વર્લ્ડ હૅલ્થ ઑર્ગેનાઈઝેશનની માન્યતા મુજબ, ટાઈપ 1 પ્રકારના એફજીસીને ક્લિટોરલ હૂડ અને/અથવા ક્લિટોરિસ કાપવા તરીકે વર્ણવવામાં આવ્યું છે, જેના ઘણાં શારીરિક અને માનસિક દુષ્પરિણામો જોવા મળે છે જેમ કે, ચેપ લાગવા, વધારે પડતો રક્તસ્ત્રાવ થવો, પેશાબ કરતી વખતે બળતરા થવી વિગેરે. ઘણી જુવાન છોકરીઓ વિશ્વાસઘાત, અસહાય અને મૂંઝવણ મહેસુસ કરતી હોવાના કારણે,આ પ્રથા માનસિક આરોગ્ય પર પણ વિપરિત અસર કરી શકે છે. તેમજ, આ આઘાતના પરિણામે, બાળક જાતિય સંબંધ બાંધવામાં પણ ડર અનુભવી શકે છે અને તેમનામાં સમાજના સભ્યો પ્રત્યે અવિશ્વાસનું નિર્માણ પણ થઈ શકે છે. પરંતુ, હજારો બૈરીઓએ આ પ્રથાને અનુસરી છે અને દાવો કરી રહી છે કે તેમને કોઈ જાતિય સમસ્યાઓનો સામનો કરવો પડ્યો નથી? જે રીતે અધિકાંશ લોકો તેમના બેડરૂમમાં શું થાય છે તે વિષે અન્ય લોકોને વાત કરતા નથી, તેમ એફજીએમના સર્વાઈવરો પણ તેમની સેક્સ લાઈફ વિષે જાહેરમાં વાત કરતા નથી. તેમાંની ઘણી બૈરીઓ પીડાથી ચીસો પાડતી હોય છે અથવા “બેડરૂમમાં”એક આરોગ્યપ્રદ જીવન જીવી શકતી નથી.તેમાંની ઘણી બૈરીઓ ડૉક્ટરો, સેક્સોલોજિસ્ટ્સ, કાઉન્સેલર્સ અને થેરૅપિસ્ટ્સની નિયમિત દરદીઓ હોય છે.હાં, તેઓ ગર્ભવતિ થવાનું (જે આજે મરદ સાથે અથવા મરદ વિના કરવું વધારે મૂશ્કેલ નથી) મેનેજ કરી લે છે પરંતુ, શું એ પ્રક્રિયા પીડા મુક્ત છે? નહીં. બધા લોકો ડિવોર્સનો દર વધવા વિષે વાતો કરે છે પરંતુ, આ દર શા માટે વધી રહ્યો છે તે કોઈ સમજતું નથી. તેઓ એ જોતા નથી કે બૈરીઓ પર તેમના ઉછેર દરમિયાન જ ઘણાં બધા નિયંત્રણો લાદવામાં આવે છે. મરદ હોય કે બૈરી, તેને સંબંધી બધી બાબતો પહેલાંથી જ નક્કી કરેલી હોય છે, આ એવું નથી લાગી રહ્યું કે આપણે એવા સમાજમાં મોટા થઈ રહ્યાં છીએ જ્યાં નેતાઓ અથવા સ્વતંત્ર નિર્ણયકર્તાઓને ઉછેરવામાં આવી રહ્યાં હોય. આપણે બ્રેઈનવૉશ કરેલા શિષ્યોના એક ટોળાં જેવા છીએ અને હાલનાં, #metoo ની ક્રાન્તિને કારણે બૈરીઓએ તેમનો અવાજ ઉઠાવવાની એક શરૂઆત કરી છે. મારી સ્ટોરી હાં, મારા પર પણ ‘ખતના’ પ્રક્રિયા કરવામાં આવી હતી. મને બધું તો યાદ નથી પરંતુ, અમુક બાબતો યાદ છે. મને “કોઈ આન્ટી” ને મળવા લઈ જવામાં આવી હતી અને મને યાદ છે કે ત્યારે મને કોઈ સારી લાગણી નહોતી થતી પરંતુ, આપણને જેમ કહેવામાં આવે તેમ આપણે કરીએ છીએ. અમે કલકત્તાના તેના અંધકારમય ઘરમાં ગયા અને તેણીએ મને ભારતીય શૈલીના શૌચાલય પર પહોળા પગ કરીને ઊભા રહેવા માટે કહ્યું અને મને લોહી નીચે પડતું દેખાયું. બસ મને આટલું જ યાદ છે. મને બરાબર યાદ છે કે ત્યારપછી અઠવાડિયા સુધી મને પેશાબ કરવામાં પીડા થતી હતી. આ ચર્ચા રાત્રિભોજનની ચર્ચા જેવી ઔપચારિક ના હોવાથી, ત્યારપછી તે વિષે ક્યારેય વાત કરવામાં આવી નહિં. 16 વર્ષની ઉંમરે, જીન સૅસનની બૂક – પ્રિંસેસ દ્વારા મને આ ‘મુસ્લિમ પ્રથા’ વિષે ખબર પડી. સાઉદી અરૅબિયામાં બૈરીઓ સાથે કરવામાં આવતી ભયાનક બાબતોની સાથે-સાથે આ પ્રથાનું વર્ણન કરવામાં આવ્યુ હતું જેણે મારી યાદ તાજા કરી દીધી હતી. પહેલાં તો હું ડરી અને ભયભીત થઈ ગઈ અને મને સમજાતું નહોતું કે આ માહિતીનું શું કરવું.મને એ બાબતસમજાઈ નહિં કે શા માટે કોઈ મારી સાથે આવું ભયાનક કૃત્ય કરે? તેનો ઉદ્દેશ શું હતો? શું કોઈ ધાર્મિક કારણ હતું? શું કોઈ તબીબી કારણ હતું? ધીમે-ધીમે હું મારી ઉંમરના અન્ય લોકોને તે વિષે પૂછવા લાગી.ઈન્ટરનેટ મારી મદદે આવ્યું અને મેં આ ‘જંગલી’ પ્રથાને વધારે સમજવાનું શરૂ કર્યું કે કેવી રીતે તે આપણા પિતૃપ્રધાન દુનિયાની

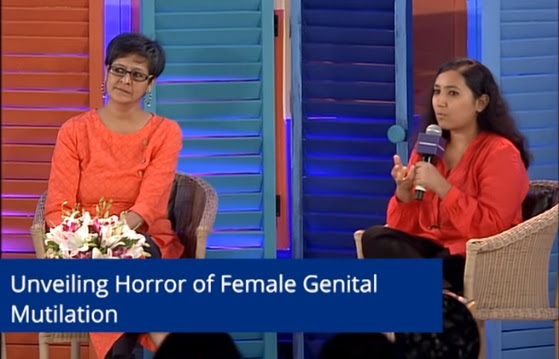

Aarefa Johari and Masooma Ranalvi discuss FGC at We the Women Bangalore

On October 7, Sahiyo co-founder Aarefa Johari and We Speak Out founder Masooma Ranalvi participated in a panel discussion on Female Genital Cutting in India, at the We the Women summit organised by veteran journalist Barkha Dutt in Bangalore. Prominent human rights activist Srilatha Batliwala moderated the discussion. The event was attended by more than 200 people in Bangalore and was streamed live on social media. Ranalvi and Johari shared their personal experiences of being subjected to FGC and discussed various aspects of the problem from the need to engage with the community to end the practice and the significance of a law against it. You can watch the complete video of the discussion here. The event was a follow up to a similar We the Women summit in Mumbai in December 2017, when Sahiyo co-founder Insia Dariwala spoke about the practice along with Mubaraka and Zohra, two survivors of FGC. You can watch last year’s video here.

Is the Dawoodi Bohra community truly as progressive as it claims to be?

By Saleha Country of Residence: CanadaAge: 45 Having lived in South-East Asia, and being exposed to multiple races and cultures, I grew up in a very open-minded family. As a child, my family and I occasionally went to the local Bohra mosque to socialize with others in the community. I loved going to the “masjid” – there I got a chance to meet my best friend and also eat delicious Bohri food. It was wonderful to see all the aunties dressed up in “onna ghagra” which are colourful skirts with matching chiffon scarves draped around the head. After the prayers, everyone congregated outside and chatted into the late hours of the night. Then suddenly in the early 90s it all changed. The upper echelons of the Bohra clergy instated new rules. The progressive Dawoodi Bohras were no more; instead, women were forced to wear a form of hijab called “rida” and men were made to sport a beard, wear a kurta, and “topi” or a cap on their heads. The clergy, headed by the Syedna, began to exert control over everything. Permission from Syedna was required not only for religious matters but in daily life as well. For example, permission was needed to start a business, get married or even to be buried. Female Genital Cutting or khatna was deemed necessary, even though that act of it is not prescribed in the Koran. If any of the rules were not followed, or if you protested and spoke against them, you were excommunicated or threatened to be. You’d lose all your ties to friends and family forever. I can never forget the awful day, when I was seven, while on a holiday in India, my aunt asked me to go shopping with her. She took me to a dingy place where a Bohri man and woman took me inside. They asked me to undress waist down, and when I protested, the man held my hands while the woman removed my jeans and underwear and forced me to lie down. I saw the man take out a blade and I struggled and screamed for help, while they proceeded to cut me. I lay bleeding on the floor, unable to comprehend what had happened to me. It was horrific, painful, and demeaning. I hated what was done to me. I hated that my mom was not there. I was angry at my aunt for allowing them to hurt me. I remember that experience vividly and to this day I am infuriated that I had to go through this ordeal as a child in the name of religion. While the majority of the Muslim communities around the world have spoken against this, the Dawoodi Bohra religious authorities urge continuing FGC under the guise of cleanliness. The worst part is that some women push this practise on vulnerable children too young to give consent, instead of protecting them as adults should. It was a difficult time for me. Having grown up with all the freedom in the world, it was suddenly being taken away from me and I grew cynical of my Bohra culture and wanted no part of it. Today, I am happy I decided to leave the fold. It was not hard to leave. In fact, it was liberating. I was not comfortable with the more rigorous path that my community was taking. I am sure there are many other Bohri people out there who are quietly questioning many of the beliefs handed down to them – some so silly, useless, and others very damaging – Bohris must refrain from using Western toilets; Bohris cannot host or attend wedding functions in secular, non-Bohra venues; brides can apply mehndi only an inch below the wrist and cannot hold the traditional “haldi” functions; and all Bohris must carry a RFID photo ID which will monitor attendance to the mosque. Humanity has achieved such remarkable progress. We have ventured into space, developed cloning and gene editing technologies, and most importantly, the Internet has resulted in globalization and interconnection between various cultures and communities. In this light, I wonder why we are still talking about FGC and the right to choose to do it to our daughters in this day and age? I am thankful that organizations like Sahiyo and We Speak Out have become a voice for children who are being hurt in the name of religion. I look at my children and I see the most informed, connected, and progressive generation. Imposing impractical, harmful religious rules such as continuing FGM on such a generation will only drive them further from our culture. More and more Bohri women and men are speaking out against this harmful practise because whenever religion becomes too rigid, too corrupt, it begins to crack. My hope is that our community can find the strength to break free from all the rigid practices and once again become the most progressive community among the Muslims.

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Work of the devil?

By: Koen Van den BrandeAge: 56 Country: India I rarely speak of the devil. In Germany they have a saying: Du sollst den Teufel nicht an die Wand mahlenLiterally this translates to ‘Don’t paint a picture of the devil on the wall’. Loosely translated it means that you should not invite evil by talking about it. But maybe there are times we have a duty to alert others to the devil’s work. What I mean by that is not that anyone in particular is a devil but rather that maybe at times the devil has a hand in misleading people. My efforts to get to the bottom of the origins of the practice of ‘khatna’ – what the rest of the world calls ‘Female Genital Mutilation’ (FGM) – in the Suleimani community, recently led me to the inevitable conclusion that the devil has had a hand in twisting the words of the Prophet PBUH, to mean the opposite of what He was saying. My attention was drawn to some research carried out by learned members of the Muslim community. Let me present the facts to you so that you may come to your own conclusion. Early on in my own research I came across a Hadith – a reported saying of the Prophet – which was being quoted as evidence of tacit approval of this ancient practice, which predated Islam and may have been initiated in the distant past to subdue the sexual urges of female slaves. My discussions with members of the Suleimani community had made it clear that the Daim-ul-Islam is the rulebook to which many show an unquestioning allegiance. Of course such blind faith can have dire consequences. The Daim-ul-Islam does indeed refer to the Hadith in question. Following is an extract from a paper published on www.alislam.org, with the title ‘Female circumcision and its standing in Islamic law’. But it turns out this is not the full Hadith. In full, the Hadith seems to leave little doubt as to where the Prophet stood on this matter. The authors of the report quote from Al-Kafi, a respected Shiite book of traditions. Was the Prophet endorsing, encouraging or even mandating that women should be cut? Or was he signaling his disapproval and in the face of a long-established tradition, trying to limit the harm done to women? Given what he says, is it correct to claim, as some do, that he should have forbidden it, if he really felt it was wrong? I will leave it to you to draw your own conclusion. For me these words of Mohammed, now in full view, are consistent with other issues where he championed the rights of women in the face of a culture which at that time saw no reason to do so. Who decided to shorten the hadith and to what end? And at which point did a woman who ‘used to circumcise women slaves’ become a woman who ‘used to circumcise girls’? There is a substantive difference is there not? Just as with the modern day suggestion that Mohammed condoned wife-beating, when in fact he counseled restraint and suggested several alternative ways of resolving marital disputes or the insistence by some on the validity of ‘triple talaq’ divorce, where in fact careful mediation over a period of time is prescribed, one can only conclude that the devil himself has repeatedly sought to undermine the Prophet’s cause as champion of the rights of women! Today we call this ‘fake news’ and we are learning day by day, how it is used to mislead those who believe without questioning. Witness how the young parents of our community are systematically fed disinformation, building on that same principle of blind faith. But blind faith in whom? I quote from the website www.islamqa.com. Search for the term ‘khatna’ and the following question is addressed, among others: This is how the scene is set: I wonder what a properly qualified medical practitioner would make of some of the advice given. Need I say more ? How do we tackle such blatant attempts at misleading parents of young girls? Surely the best strategy must be to focus on facts and truth. So I am attempting to find a consensus across the Suleimani community around the following statement. “I as a member of the Suleimani Jamaat, in the interest of young parents and their girls, want to reflect what I believe to be the truth about the practice of khatna. Fact is … It is a tradition which predates Islam It is not mentioned in the Quran at all It is not practiced by all muslims It has been declared a crime in several Muslim majority countries It is considered a health hazard by the World Health Organization It is considered a crime against a child by the United Nations Truth is, in my humble opinion, that the Prophet Mohammed PBUH frowned upon this practice and sought to prevent harm from being done to women. I believe that these facts should be endorsed by our leadership and communicated to all of the Jamaat ‘s young parents. The Daim-ul-islam states that ‘khatna’ is not obligatory and that it should not be performed before a girl is 7-years-old. I believe that it would be in line with this rule to recommend to parents that any decision to proceed with this practice should be postponed until the age of consent. And in line with the Prophet’s guidance, at a time when it was a more common practice, I believe that when and if it is performed, it must be done symbolically only and cause no harm.” I hope you can join the effort by endorsing this statement. And if you cannot, I invite you to propose an alternative. At least let’s start by banning the use of http://www.isllamqa.com Let us work together to undo the work of the devil. This blog is the third in a three-part series that describes the practice of FGC within the Suleimani Bohra community.

Not all damages are physical. Not everyone religious is morally ethical

Name: Xenobia (name changed) Age: 27Country: India Today, social media is raging with thoughts and opinions on empowering women, being pro-choice, violating someone’s privacy and their body, and the role of consent, among others. Some say rapists must undoubtedly be hung to death, while some talk about punishing molesters and eve-teasers as well, so that the right patterns are set at the grassroots level and so that they think twice before taking advantage of girls again. But what happens when the people taking advantage of a helpless 7-year-old girl are none other than her own family and community? Who, then, takes accountability for that? I’m not going to cry about my personal story here, but present some basic facts for you to consider. I am a Bohra Muslim raised in India. While the world sees us as a non-confrontational, peace-loving, business-thriving community, we have a secret tradition of circumcising 6-7-year-old girl children that we call khatna. There are plenty of arguments about how this is “needed” from a health point of view for males and how it helps them in their sex life eventually, but the most educated and civilised people agree that this practice is harmful to a woman’s physical, psychological and emotional health, especially since it is not supervised or is often performed by untrained aunties in basements. This practice is officially termed as “Female Genital Mutilation” (FGM) everywhere else in the world and it is increasingly treated as a crime committed on helpless female children. Why? What’s the reason? Some say purity, some say patriarchy. Some do it because it’s a mandatory tradition and if the priest says so, who dares to refuse? Some do it out of peer pressure, some do it to avoid being blacklisted or labelled rebellious. The popular conclusion for those seeking out answers has been, to moderate or curb a woman’s sexual desires. Sure, this might have worked well in an era when we lived in deserts and tribes were always on the lookout for stealing another’s woman. Irrespective of the reason today, does it even matter? However good your reasons may be, you still don’t have the right to decide what to do to a woman’s body without her consent. Whoever you may be. No matter what your intentions, the damage is done and you are still no different from a criminal. So what does this mean for the victims? The custom practiced by us is allegedly ‘Type 1’ and is different from that practiced by some African communities – Type 2 and Type 3 (based on levels of severity). As recognised by the World Health Organization, Type 1 FGC is described as the cutting of the clitoral hood and/or the clitoris, which poses a range of physical and emotional consequences such as infections, excessive bleeding, burning sensations while urinating, etc. The practice can adversely affect mental health as well since many young girls feel personally betrayed, helpless and confused. The child can also experience fear of sexual intimacy and mistrust of community members later in life as a result of the trauma. Sounds familiar? But aren’t there thousands of other women who have gone through the same thing, and claim they are not facing sexual problems? Just like most people don’t talk to others about what happens in their bedrooms, there are FGM survivors who don’t talk about their sex lives in public either. Some of them scream in pain through the night or are unable to have a healthy “bedroom life”. Plenty of these women are regular patients of doctors, sexologists, counsellors, and therapists. Yes, they manage to get pregnant (which is not very hard to do, with or without a man) but is the process peaceful and pain-free? No. Everyone talks about divorce rates going up but nobody realises why. They don’t see that in general, women are subject to a lot of curbing throughout their upbringing. Things have always been decided for them and whatever the gender might be, it’s not like we are brought up in a community that breeds leaders or independent decision makers. We are a herd of brainwashed followers. And with the recent #metoo revolution, women have just started discovering their voice. My personal take Yes, I was ‘cut’ too. I don’t remember the details, but I remember flashes. I was taken to meet “some aunty” and I remember not having a very good feeling about it, but you do what you’re asked to do anyway. We went to her gloomy house in Calcutta and she asked me to stand over an Indian-style toilet with my legs apart and I remember seeing blood fall. That’s all. I definitely remember having a hard time peeing for a week after that. Since this clearly does not qualify as a regular dinner conversation, it was just never spoken of after that. At age 16, I came across this ‘Muslim practice’ in Jean Sasson’s book – Princess. Among other terrible things done to women in Saudi Arabia, this was described in detail and that awoke something in my memory. At first, I was scared and terrified because I didn’t know what to do with that information. It didn’t make any sense. Why would something that awful be done to me? What was the purpose? Was this religious? Was this medical? Gradually, I started asking other people of my age about it. Thanks to the internet, I started understanding a lot more of this ‘barbaric’ practice and how it is just another side effect of our patriarchal world, where random men decide how we must lead our lives and what is good for us. What I couldn’t wrap my head around was how parents would let that happen to their own kids. When your daughter is at the peak of her innocence and brimming with nothing but pure love for you, you violate that basic trust. And then you actually hand her over to the monster who does that to her? So your religion asks you to