The movement to end FGM/C: Looking back at the 2010s and looking forward in 2020

By Sahiyo 2020 is here, and we at Sahiyo are excited. 2020 brings with it not just a new year, but the dawn of a new decade of hope and hard work for our global movement to end female genital cutting (FGC). This is the decade in which we must give it our all, because we have pledged to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of eliminating Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting by 2030. As we look forward to the 2020s, we cannot help but look back at the 2010s for inspiration. The last decade has been game-changing, not just for Sahiyo or the movement against FGC among the Dawoodi Bohras, but for the anti-FGC movement in Asia as a whole. At the start of 2010, FGC was still considered an “African” problem, and Asian countries were barely on the map of the places where FGC is prevalent. Today, we know that FGC is truly and disturbingly a global phenomenon putting 3.9 million girls at risk every year, as you can see in this map created by Orchid Project: Nearly half the countries on the map above are not yet included in the UN’s official list of 30 countries where 200 million women and girls have undergone FGC. In the 2020s, let us work to ensure that this information gap is bridged, so that Asian survivors of FGC are officially recognised. In fact, you can start now by signing Sahiyo’s petition asking the global community to invest in research on FGC prevalence and advocacy and support services to end FGC in Asian countries. But first, let’s take a look back at the biggest milestones of the 2010s from Sahiyo’s perspective. The birth of Sahiyo: In late 2011, ‘Tasleem’, an anonymous Dawoodi Bohra woman from India, started a Change.org petition asking the Syedna, the religious leader of the Dawoodi Bohra sect, to call for an end to FGC in the community. Although there had been scattered attempts to call out the secretive practice of FGC among the Bohras in the 1980s and ‘90s, they drew limited attention and the practice continued to be shrouded in silence. Tasleem’s petition, however, received nearly 3,500 signatures, triggered a spate of media reports on FGC in India, and inspired a few Bohra women, like Aarefa Johari and Farida Dariwala, to speak out publicly about their experiences of FGC. The media reports on FGC at the time also inspired Sahiyo co-founder Priya Goswami to make A Pinch of Skin, the first documentary film on FGC among Dawoodi Bohras in India. As Goswami’s film won the 2013 National Award for the best documentary in India, the taboo topic of FGC remained alive in the media, sparking private conversations between like-minded Bohra women all over the world who were keen to see an end to FGC. In late 2014, five of those women banded together to create a formal platform that would work to end FGC among Bohras and Asian communities at a transnational level. That platform — Sahiyo — was eventually founded in mid-2015. Breaking the silence, once and for all: In 2015, the private conversations on FGC among Bohras also burst into the public sphere with the launch of WeSpeakOut (known as Speak Out on FGM at the time). WeSpeakOut started as a private women’s WhatsApp group spearheaded by Masooma Ranalvi. In October 2015, the group launched a Change.org petition addressed to the Indian government, seeking a legal ban on FGC in India. Seventeen Bohra women publicly put their name to the petition, and the response was huge and immediate: media all over India began writing about FGC among Bohras, community leaders were forced to respond, and the silence about FGC among community members was broken for good. More than 200,000 people have signed the petition so far. From 2015 to 2019, we have watched the movement against FGC snowball into a global force that communities have not been able to ignore. There are now dozens of Bohra women fearlessly speaking out about their FGC experiences, signing up as Sahiyo volunteers, attending our events and pledging not to cut their daughters. Women and men have faced backlash from their families and communities for speaking out, but the movement has only grown stronger. Research and investigations: In February 2017, Sahiyo released the results of the first-ever research study on FGC among Bohras: an online, exploratory survey that found an 80% prevalence rate of FGC among Bohra women respondents. Among those who were cut, 98% women reported feeling pain when they underwent the ritual. Interestingly, 81% of respondents did not want FGC to continue in the community. In 2017, a Sahiyo investigation also revealed that FGC is being practiced by some communities in the South Indian state of Kerala, leading to furore in the region. Before this, it was believed that the Bohras are the only community in India practicing FGC. In 2018, WeSpeakOut published a seminal field study on FGC among Indian Bohras. The study found FGC prevalent among 75% of the daughters of the respondents. At least 33% of the respondents who were cut reported that FGC negatively impacted their sexual lives. More research on the FGC in Asian communities is the need of the hour, and we are aware of several studies that are currently underway in various parts of Asia. Continuous research can help us better understand not only the prevalence and impact of FGC on women and girls, but also the needs of survivors and trends towards abandonment of the practice. Developments on the legal front: The 2010s were a landmark decade for FGC on the legal front, particularly for the Dawoodi Bohra community. Australia: In 2015, three Bohras — a mother, a nurse and a community leader — were convicted for performing FGC on two minor girls in Australia. This was Australia’s first case under its 1997 law banning FGC. However, the legal ups and downs did not end with the conviction in 2015. In 2018, an appeals court overturned the convictions

Global Call to Action From “Uniting forces to make female genital mutilation/cutting a practice of the past: A gathering for global civil society actors”

On June 2, 2019 in Vancouver, Canada, civil society organisations, champions, survivors and other grassroots representatives came together at Women Deliver 2019 to unite voices around a global Call to Action to end female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). The pre-conference was an unprecedented gathering as a sector working globally across the issue to discuss what is needed to accelerate ending FGM/C by 2030. The event put grassroots voices at the centre and worked to strengthen our unified community of practice to support the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 5.3. (eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation). “Uniting forces to make female genital mutilation/cutting a practice of the past: A gathering for global civil society actors” involved more than 100 participants in Vancouver. More than 270 additional participants shared their expertise and experience through an online survey. The event was co-ordinated through a core group of globally representative organisations that managed logistics: Amref Health Africa, Coalition on Violence Against Women, End FGM Canada Network, End FGM European Network, Equality Now, Orchid Project, Sahiyo, The Girl Generation, The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices, The US End FGM/C Network,There Is No Limit Foundation and Tostan. Participants in Vancouver endorsed the following Call to Action: PREAMBLE FGM/C is a violation of the human rights of women and girls and must be ended in all its forms We need to make FGM/C a global priority, in the same way the global community responded to other global epidemics, such as HIV/AIDs SUPPORTING CHANGE FROM WITHIN – CHALLENGING SOCIAL AND GENDER NORMS We share a vision of a world free from FGM/C and will work in partnership with each other, all communities, governments, donors, multilateral bodies and others to end the practice by 2030 in line with the SDGs Whole communities must be mobilised and empowered at the grassroots level if we are to end FGM/C – women and girls, men and boys, traditional and religious leaders, health workers Ending FGM/C requires addressing the root causes of gender inequality at the community level, including gender stereotypes, unequal power relations, and negative social norms STRENGTHENING THE EVIDENCE BASE THROUGH CRITICAL RESEARCH Fill the knowledge gap on FGM/C survivors’ specific needs, impact on economic empowerment, and behaviour change around emerging trends such as medicalisation and lower ages of cutting Use community-based participatory approaches within research efforts and ensure that research results and data are synthesised for communities to use Create, test, and implement standardised universal indicators that are informed by context specific measures and demand country-level reporting IMPROVING WELLBEING VIA SUPPORT AND SERVICES FOR SURVIVORS More support is needed for survivors in various forms, including security and protection for survivors, targeted research and resources to enable health and emotional wellbeing Enable the transformative power of survivors and survivor-led networks through support to connect with each other, other gender-based violence movements and capacity build ADDRESSING EMERGING TRENDS AROUND FGM/C We need an integrated, intersectional approach to ending FGM/C recognising the connections with other forms of gender-based violence and linking with existing movements We are committed to working with religious leaders, health workers and governments to respond to adaptations to the practice which continue to violate women’s rights, such as medicalisation, cross-border practices, and lowering the age at which FGM/C is carried out INCREASING RESOURCES TO ACHIEVE THE GLOBAL GOAL We call on all stakeholders to prioritise resources towards grassroots and community-led programmes. Funds should be more flexible, sustainable and accessible for communities and grassroots and capacity building should be provided as well as networks Investment is needed in better research into what is working and what is not to end FGM/C. This research needs to be participatory and involve multiple stakeholders and should be made available and accessible We are focused on coming together and working collaboratively to address what existing gaps there are, what are the costs of FGM/C, and what do we need to end this globally See call to action as PDF here. Further Women Deliver blog posts: Joint Press Release: Ending FGM/C BY 2030: Uniting forces to make FGM/C a practice of the past Multiple events on FGC hosted at Women Deliver in Vancouver

PRESS RELEASE: A pioneering Roundtable to Address Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Massachusetts

Download press release as PDF PRESS RELEASE: A pioneering Roundtable to Address Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Massachusetts Boston, Massachusetts, 14 June 2019 On June 13, 2019, a collective of almost 60 experts from different disciplines and cultural groups took the first steps to create a ‘Massachusetts End FGM/C Network’, to highlight the largely unrecognized global issue of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, and to share knowledge and resources to help end the practice. The experts gathered to attend the first of its kind roundtable to address FGM/C in the state of Massachusetts. They included community leaders, civic society organizations, health professionals, state government officials from the Massachusetts Legislature, and the Massachusetts Office of the Child Advocate, and federal government officials from the Department of Justice, and Department of Homeland Security Investigations. The event was organized and led by Sahiyo, a storytelling organization working to support survivors of FGM/C, with support from co-sponsors Muslim American Leadership Alliance (MALA), Tostan, MassNOW, Lesley University, the US End FGM/C Network, and the Women’s Bar Association of Massachusetts. A prevalence study conducted by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention reveals that in 2012, over half of a million women and girls in the United States had FGM/C performed on them or were at risk of FGM/C. Massachusetts ranks 12th in the nation for at-risk populations, totalling 14,591, with the largest at-risk metro areas being Boston, Newton, and Cambridge. “I’ve undergone FGM/C and I know FGM/C is a global issue affecting women of all different ethnicities, religions, cultures, socio-economic status, and more,” said Mariya Taher, Sahiyo Cofounder and U.S. Executive Director. We need a global response to ensure future girls do not undergo it. We need to think globally and act locally.” “All are about the cultural control of women’s bodies,” s aid Representative Jay Livingstone in reference to FGM/C. Livingstone is a former prosecutor and co-lead sponsor of the Massachusetts FGM/C criminal bill – H. 3332 who connected the dots between this recent bill to Massachusett’s Equal Pay Act and other pending state legislation, such as The Roe Act. Rep. Livingstone expressed his hope that the FGM/C had bi-partisian support during this legislative session and would pass this session. Dr. Melody Eckhart, an OB/GYN at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Dr. Sondra Crosby, an internist at Boston Medical Center, spoke about their experiences working with patients who have undergone FGM/C and physical complications that can result, including shock, pain, hemorrhage, infection, and anemia. They warned of the long-term consequences of scar tissue and cyst formation impeding proper urination and menstruation, sexual dysfunction, and complicated labor and delivery, as well as fetal demise. They also called on the urgent need for educating health professionals on how to care for survivors — including addressing their psychological and emotional needs. “FGM/C is shrouded in secrecy even in the medical community,” said Dr. Crosby. “Health professionals need training in how to work with women in non-judgemental ways, how to make referrals, and how to treat the medical and psychological consequences of FGM/C, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Medical personnel need to understand the women’s FGM/C experience before they could diagnose and treat it.” The roundtable was a vital first step to create a multi-disciplinary working group that works to protect all girls in Massachusetts from experiencing this form of gender-based violence. For more information, contact Lara Kingstone at communications@sahiyo.com

‘A Pinch of Skin’ to Screen in Berlin

Sahiyo co-founder’s documentary ‘A Pinch of Skin’ will be screening at NaturFreudeJungend in Berlin on the 25th May. 25th May is also the one-year anniversary of the historic repealing of the ban on abortion in Ireland, also known as the 8th Amendment. This is especially significant as a successful contemporary feminist movement, where women of Ireland voted against the ban on abortion, influencing pro-choice ideas in the Irish constitution. Goswami will be joined by a pro-choice activist from Ireland, Dervla O’Malley and Dr. Tobe Levin von Gleichen, Female Genital Cutting/Mutilation activist, for a panel discussion post the screening. The discussion will aim to look at practices and cultural ideas such as Female Genital Cutting, stigma on abortion, menstruation taboos which try to control the female body and sexuality.

A tale of deception: My conversation with an FGC survivor in Pakistan

By Hina Javed (This is the third part in a series of essays by Hina Javed on her experience of reporting on FGC in Pakistan. Read the whole series here: Pakistan Journal.) The time had come to pick up that phone. Little did I know that my conversation with an FGC survivor would be more harrowing for me than the talk which revealed its existence to me in Pakistan. I picked up the phone and made contact with my second survivor, 37-year-old Sophia. The woman narrated the time when she, just a girl of seven, was led into a dimly-lit room, full of strange odors and even stranger people. This was not the shopping trip the minor had in mind when she was told earlier in the day that her aunt was taking her out. As if the surroundings were not distressing enough, the girl was forced to lie down on the floor and soon a complete stranger was reaching between her legs. The moment she was ‘cut’, she let out a loud scream and tears started rolling down her face. When it was over and done with, the matter was hushed up and never spoken of again. Three decades on, a now grown woman remembers vividly the day her freedom of choice was taken away: I still remember it distinctly. I feel slighted, even to this day, at how they held me down despite my attempts to push them [the strangers] away. But most of all, I feel angry at how they buried the matter under blankets of silence and pretended like it never happened. The day I walked out of the dingy apartment, I thought I was punished for being ‘bad’. I was mortified to look even look at the cut. I wanted to lie down in my mother’s lap and forget everything; to assume, for a split second, that what existed between my legs wasn’t shameful. When I grew up, I was finally able to connect the dots. The ‘cut’ was a symbol of my sexual submissiveness. Just like vaccinated animals, I was now wearing an imaginary ear tag signifying the death of the ‘parasite’ [or bug] driving my sexuality. From then on, I was to be categorised as a woman of ‘decent’ character. The truth is, I was just another offering to a centuries old tradition. The decisions made about my body came from a group of elderly women who believed it was a necessary rite of passage. And the cherry on top was that I was made to kiss my hostess’s hands as a gesture of respect. I didn’t speak about the incident for the longest time. I feared it would be considered rude and impolite. But there came a point when it became difficult to contain my angst and disappointment and I ended up asking my mother. I now realize that it wasn’t her fault either. I wonder if my anger towards my mother was even justified. Without a shadow of doubt, she was under immense pressure from family elders. If she tried to get away with it, they would have found out and ostracised her from the community. I am now a happily married woman with two beautiful children, but I feel a sense of deep remorse when I engage in sexual activity. I feel immoral, sinful and unclean. The trauma is so deep that the act itself becomes an unpleasant experience. It is difficult to be psychologically scarred and feel completely at ease. Sadly enough, our generation still believes sex is a dirty, reproductive act. We are trained to associate sexuality with immorality. We grow up with warnings that if we express our desires, we are deviant and dirty. We have spent our entire lives in the absence of this conversation, but we need to have it anyway. This avoidance has robbed several women of their identities. I have tried to bring this up many times with little progress. I am already estranged from my family over disagreements. What is surprising is that these decisions are made by women. The misogyny is so deeply internalized that they are unable to look squarely at the sexist world around them. Upon hearing Sophia’s story, I recognized the extent of psychological and physical damage the ‘cut’ had on her. She was in perpetual dilemma: on the one hand she wanted to speak up about her experience, but was also overcome with guilt and fear. It was evident that she was unable to shake off the impact of the incident to this day. As she finished speaking, there was a momentary pause as I struggled to thank her for speaking up about her experience. “I wish I could allow you to quote my name. There is a dire need to elevate this conversation in every country, especially Pakistan. However, there is immense pressure from my community due to which I want to remain anonymous,” she said. “I understand,” I replied. “I hope your story stirs a conversation and becomes a movement in this country. We need to put an end to this contested practice.” (*Sophia is a pseudonym. The person’s original name has been changed to protect her identity.) (Hina Javed is an investigative journalist based in Pakistan, driven by the ambition of tackling difficult, often untouched topics. Her focus is on stories related to human rights, health and gender.)

The unsolved riddle: conversations with survivors (Part 2)

By Hina Javed (This is the second part in a series of essays by Hina Javed on her experience of reporting on FGC in Pakistan. Read the whole series here: Pakistan Journal.) That night, after witnessing truth being replaced with the censor’s lie, I spent hours alone in my room, flinching at every little thought that crossed my mind. I sat on the tiniest corner of my bed, locked in a deep sulk. In the ensuing minutes and the quiet of that night, thoughts frantically raced through my head in an attempt to find the answer. Was the issue of female genital cutting (FGC) so intimidating that it could not be expressed aloud in the Pakistani media? Was this the way of patriarchy? It made you suffer in silence. I traced my steps back to where I had deviated from the norm. The more I struggled to solve the mystery of why my well-researched article on FGC in Pakistan was no longer going to be published, the more I was convinced that the questions would be put away in the recesses of my mind, like an unsolved riddle. In that instant, brief fragments of past conversations bubbled up in my consciousness. How bizarre it was that the reminders came flooding in at the very moment disorder took over my existence. I was now back to square one, having my first conversation with Amber* after she acknowledged the existence of FGC so matter-of-factly. “But why would you cut an innocent girl who is still tasting the sweetness of childhood?” I asked, trying to make sense of it all. “There is no harm in it,” Amber spoke with an indifference. “It makes the child pure for the rest of her life. We live in a sinful age where girls deviate when they hit puberty. Khatna is done to preserve their chastity and it’s a good thing!” I nodded, less in agreement, and more as a courtesy to show I was listening. “You know how in foreign lands girls explore their sexuality before tying the knot?” She said in an almost condescending tone. “Circumcised girls don’t indulge in such things.” Amber’s words hit me like a ton of bricks. We had been friends for some time now and frequently discussed women’s rights, consent, and feminism. In every conversation, it surprised me how much the two of us thought alike. However, this time I could not believe my ears as I listened to her justify female genital cutting. I held myself from lashing out in protest at her promoting FGC. As Amber’s friend, and not a journalist, I could have countered her justifications. But, I refrained from hurting her religious sentiments and gave her the benefit of doubt to see if I was missing a point. “But doesn’t it hurt a girl’s sexuality as she grows up?” I asked, my face scrunching up into an expression of worry. “What if your daughter doesn’t want this for herself?” “It doesn’t work like that,” Amber said, softening her tone. “There was a time when family elders used to mask reality and constantly take us by surprise. There was less communication and more innocence. But, when it came to my daughter, I mentally prepared her for it ahead of time.” I nodded, again less in agreement and more in courtesy. “The doctor asked me not to hide anything from my daughter. In fact, this doctor is so professional, she doesn’t circumcise girls without their consent.” “What was your daughter’s reaction like?” I asked in a muffled tone, full of disbelief at what Amber was telling me. “She was scared and had her fears, but she knew what was coming. After a few conversations, she made peace with it,” Amber went on. “My daughter will never blame me because I took her consent. Mothers who do it without their daughter’s consent are wrong, in my opinion. There is no harm in asking. They are girls. They will understand.” Listening to Amber made me realize how we, as a society, misunderstand the concept of consent. The definition of ‘consent’ is written in crayon; raw, unfinished, unprocessed. What is confusing to a great many people is that consent cannot be given by a minor who because of their age cannot grasp the full implications of what is happening to them. Consent is more than forcing a grudging “yes” out of someone; it means getting informed permission from a person when they have the reasoning capacities of an adult. This lack of understanding consent can cause a lifelong impact on a girl’s sexuality when they are an adult – one that is eternally painful. Amber and I gauged each other’s expressions with an uncertainty only we could discern. She was patient with my questions, but now I could feel a thought forming at the edge of her consciousness. She was wondering if perhaps I viewed her differently, thought negatively of her actions. She was starting to get a little frazzled. I changed the topic and asked her if I could call the following day. That night, I decided to pursue this topic as a story. I perused online resources and posted in a few closed forums to connect with more survivors. The mere thought of doing a thorough investigation on a topic as sensitive as FGC seemed far-fetched – almost impossible. I received several warnings from friends and colleagues asking me to back off. I didn’t. The next day, I brewed coffee, cleaned my work space, drafted the questions and called Amber. Since my journalistic hat was now on, I decided to remain neutral – barely interrupting her as she spoke. “Hello!” Amber said after picking up her phone. “Hi!” I responded. We waited for each other to fill the silence as if we had yet to discover the language in which we could really communicate on this topic. “I hope I am not being a bother,” I said after 60 seconds. “Not at all! Shoot me your questions, but

Violated hopes: My struggle to report on Female Genital Cutting in Pakistan

By Hina Javed Country: Pakistan When sporting my journalistic hat, I tend to sniff out stories from unlikely sources, wherever they are hidden. I look out for news, dropping into places to see what is new. This time around, however, I wasn’t particularly looking for a story. I was just making small talk with a friend, who I would call Amber, sipping tea in the chilly, wintry breeze; the stillness of time hanging heavy in the thin air; the late afternoon light filtering through the branches of a tree. Amber kept rambling about her married life and parental responsibilities, and how both were in permanent need of repairs or adjustments like an old car needs maintenance. I pretended to listen to her, albeit inattentively, all the while thinking about the most plausible excuse for not meeting a story deadline. And just at that moment, I snapped out of my reverie at the mention of the word khatna (also known as circumcision). Suddenly, my eyes and ears were attentive, in perfect union. In that rare and curious moment, I dared to ask her if she was talking about Female Genital Cutting, a practice I thought did not exist in Pakistan. For a split second, I thought I might have violated an unwritten code of ethics. Maybe I had not phrased the question to fit the language of social architecture. It was too late now, but I still tried to rephrase the question, spitting out tiny fragments of sentences; struggling to find the right words, and dwelling on the worst possible response. The response was startling, if not dreadful. All this while, she was complaining about her 10-year-old daughter who had recently been cut and refused to urinate for several hours. Amber was worried that her daughter would develop an infection if she held it for too long. Perhaps, for me, this was the worst part. This limbo of not knowing whether to ask more questions, given the sensitivity of the topic. But, I gave in and flooded her with queries. If there is one thing Amber knows about me is that I listen keenly without ever coming across as judgmental. I assume it’s because of my profession. People never ask me what I think, and I never tell them what I think, because in my view that’s the way a journalist is ought to behave. The initial conversation got me thinking. I made several attempts to talk to Amber and determine the extent of the issue. She would mostly respond in bits and pieces, leaving me more confused than ever. One day, however, she started talking more openly; justifying the practice and expressing concerns over how misunderstood her community is. It was in that fleeting moment that I knew I had plunged into murky waters. I was ready to write my next story, except I was in a state of moral anarchy. As I investigated the matter further for my piece, I realized something important had changed. The social architecture that dismisses the inconvenient truth of FGC was changing fast, but only among the younger generation of Bohra women. Outsiders, however, were still largely unaware of the practice. These women were speaking up in numbers too big to ignore. What was holding them, however, was the horror of bringing shame to their families and a subsequent fear of revealing a reality that would rather be rationalized away. Listening to the stories of vulnerable women gave me sleepless nights. I felt burdened with a sense of responsibility too heavy for my shoulders to carry. They had expectations too great for me to fulfill; each one of them hanging on to the hope that my story will stir up a conversation in Pakistan and possibly bring an end to this practice. A month later, I had almost finished writing the story despite my own uncertainties and misgivings. In my limited experience as a young journalist, I had done stories on sensitive topics but nothing came close to this. To counter my persisting doubts, I had the story edited by a trusted senior colleague who showed nothing but the greatest respect for my brave efforts. I was finally starting to feel a sense of gratification; a tiny ray of hope for giving a voice to the voiceless. I was ready to put it out before the general public. However, the journey was far from over. The path ahead was ridden with disappointment. Pakistani media organizations refused to lay a finger on the piece due to sensitivities. I was told that I had crossed the comfort zone of the general public. The article caused a stir and went through clearance after clearance; each time censoring important chunks of information and eventually being turned down. I was aware of my country’s heavily censored media and the difficulties journalists had to overcome to report sensitive topics. However, my experience landed me on a different playing field altogether; one that was far from level. I was now a victim of the epidemic of shameful silencing. I was among the people who were hurt, humiliated, and degraded because I had made the mistake of speaking out. I had forgotten that stirring up a conversation would dismantle the stronghold of patriarchy. I was asked to retreat and swallow my resentment, to bear up and direct my fury elsewhere. Or turn it inwards. Or stomp it out altogether. As I sit here in silence, I feel the guilt of betraying the survivors and the fury of being betrayed by the so-called representatives. The former, a betrayal of hopes and expectations. The latter, a betrayal of attitudes. This unbearable pressure has crept into me like a blazing fire – at first slow but fast turning into an inferno. I exist in perpetual isolation and emotional turmoil. I am left to untangle the web of reasons why all my efforts backfired. I wallow in the awareness that no one will ever acknowledge the existence of an otherwise contested practice in my

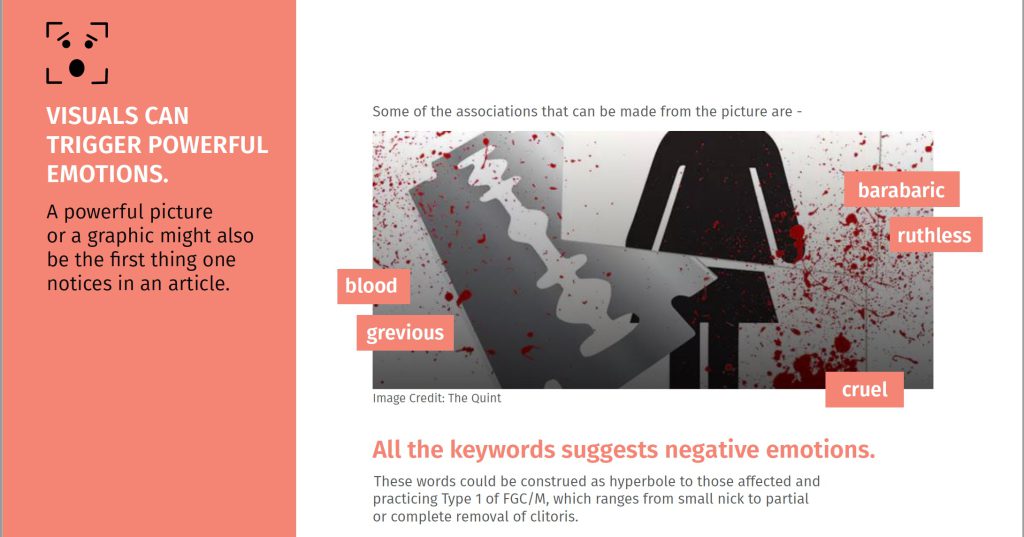

Sahiyo launches special toolkit to help the media report sensitively on Female Genital Cutting

‘All FGM causes trauma and pain’: A great video speaking of FGM/C as a collective struggle.

When Sahyog gave Sahiyo an opportunity to engage with young students