Navigating Complexity: Understanding and Addressing Challenges Faced by Kurdish Women with FGM/C

By Osman Mahmoudi UNICEF reports that FGM/C remains prevalent in Iraqi Kurdistan, affecting over half of women who live there. The profound impact of this practice requires urgent medical and psychological support for survivors. However, a lack of specialized professionals in the region, and limited awareness of treatment options and complications, pose challenges. Cultural taboos and social constraints further impede survivors from seeking help, leading to discrimination, stigma, and reluctance to access essential services. As a family counselor and psychotherapist specializing in FGM/C, I have conducted extensive research and provided psychological, sexual, and physical services to survivors and their partners. Between 2019 and 2023, I conducted numerous workshops for local teams in Iraqi Kurdistan, focusing on effective communication with survivors and providing comprehensive care. These sessions focused on understanding the complications of FGM/C and breaking the taboo’s surrounding the discussion of this practice. The workshops highlighted the lack of readily available psychological support for survivors, as well as cultural and social obstacles they face in opening up about their struggles. They also highlight how professionals – like doctors – lack awareness regarding proper treatment methods for FGM/C. However, participants’ eagerness to learn and enhance care emphasized the need for continuous education and training in this domain. These experiences underscore the potential for improving survivor care through ongoing learning and educational initiatives. In 2023, after concluding the training sessions, the educational materials used were compiled into a publication titled “Living with FGM in Kurdish Regions.” This book aims to fill a significant gap in existing literature, and serves as a guide to help survivors enhance their quality of life. The book comprises five chapters, each of which explores various aspects of FGM/C: The first chapter dives into the historical and cultural context of the practice in Iraqi Kurdistan Chapter two focuses on the challenges Kurdish women face in openly discussing their experiences Chapter three stresses the importance of addressing survivors’ physical health through comprehensive medical examinations and management strategies Chapters four and five explores the psychological and sexual impacts of FGM, offering insights into therapeutic interventions As a handbook, this publication also provides practical guidance on psychosexual therapy and social services. It marks a culture-oriented approach in the domain of “Life with female circumcision,” emphasizing the importance of respecting and empowering survivors while tailoring therapeutic approaches to their individual needs. Osman Mahmoudi is a family counseling doctor, researcher, and trainer specializing in FGM in Iran. His research aims to enhance the psychosexual well-being of FGM survivors by improving access to quality healthcare in the region. He earned his doctorate in family counseling from Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz. Additionally, Osman Mahmoudi is dedicated to advancing sexual rehabilitation for FGM survivors in Kurdistan, Iran, through his ongoing study. Related links: This Father’s Day, join our campaign Survivor Support Resources

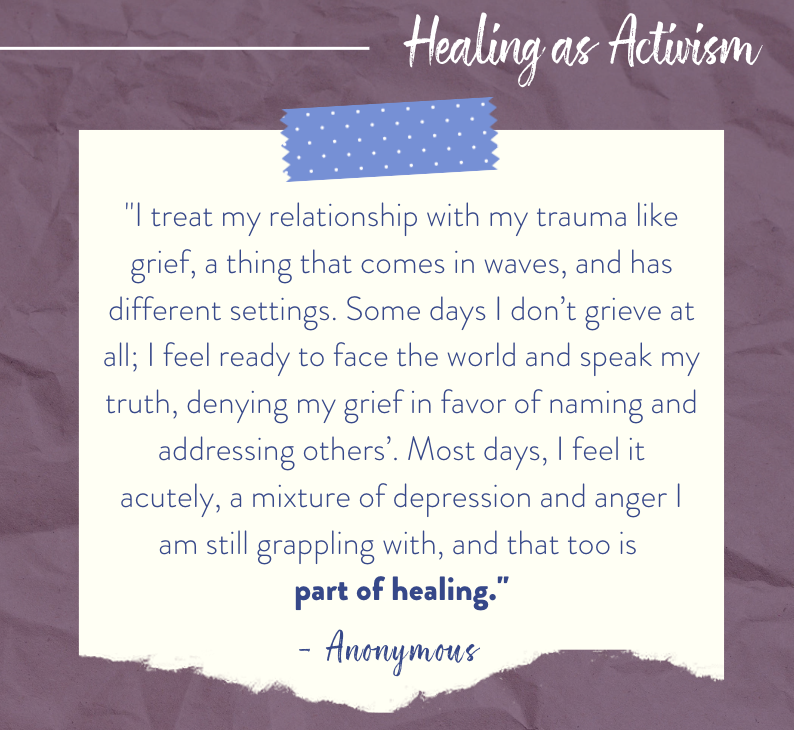

Healing as Activism: One cannot give from an empty cup

By Anonymous Emotional burnout looms over my head like my very own Sword of Damocles, waiting to strike me down for being woefully human. But the above saying travels with me, like my shield against self-doubt, offering ownership of my humanity, acceptance, and assurance that it is okay to be tired, okay to rest. The simple fact is this: one cannot give of themselves, their time or their talents, without taking too — taking time for themselves, taking care of themselves. I joined Sahiyo because of a trauma. Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and my experience with it has irrevocably marked my psyche and I will never escape those consequences. Initially, when I joined on as a volunteer, I did so because I thought activism was healing. Turns out, the opposite is more true. Activism is work. Healing from trauma is also work. Sometimes that work can be done simultaneously, but other times one must be paused to further the other. And that’s okay. As an activist, I like to think of myself as an advocate for persons known and unknown, a voice for those not quite ready to speak up — and those who cannot speak at all anymore. But who speaks for me? Who speaks when my voice is torn apart from speaking too much? Who will see me struggling to be heard and say what I can’t? One cannot give from an empty cup. Without taking time for my own mental health, without addressing my trauma, emotional burnout would have been a permanent condition. I treat my relationship with my trauma like grief, a thing that comes in waves, and has different settings. Some days I don’t grieve at all; I feel ready to face the world and speak my truth, denying my grief in favor of naming and addressing others’. Most days, I feel it acutely, a mixture of depression and anger I am still grappling with, and that too is part of healing. I find it important to name the grief, what I am feeling, and let it exist. Honor it as a friend that will, eventually, hopefully, one day leave my presence — even temporarily — so that I can make room for action again. Sometimes that honor takes the form of writing: in creating a fictional world that I control the outcome of, or in journaling, so that I can name my emotions for when I next get a chance to talk with my therapist. It may sound trite, or even potentially immature, but there is so much healing in something as simple as writing fanfiction, in creating a story with a character that is absolutely a version of myself that gets to live in a fictional world I love. That character may have faced the same trauma as me, but the questions they — and I — grapple with have easier answers in the fictional world I get to control. It’s the answers I want to hear to the questions I am a little afraid to ask aloud. Other times, that honor takes the form of community, of being with others who understand, and candidly naming the emotions we are feeling. Being with other members of Sahiyo, even for small periods of time, is a form of healing I didn’t realize I needed until I joined the 2022 Activists’ Retreat and really processed that I was not alone in what I felt. Just like activism, healing does not have to be done solo. Other times still, it is about escaping, about finding something that lets me be unplugged from it all. Turning off my notifications and disappearing into a new craft project; watching a show that I know makes me happy; resetting my thoughts and getting a good night’s sleep because tomorrow will still be there, waiting to arrive, and the work will still be there, waiting to get done, and the journey does not always have to be about moving forward. Sometimes, it can be about resting. One cannot give from an empty cup. I cannot give my time or energy to Sahiyo without first dedicating time and energy to myself. The greatest lesson I have learned on my healing journey is that I must be my greatest advocate, must learn when I need to step back and lean on the love of friends and family to refill my cup so that I can give again. Without taking steps to care for yourself, it becomes harder and harder to care for others. Choose activities that honor your talents and your interests. Choose people who will support you, will speak for you when you are tired. Your cup may never runneth over, but it doesn’t have to run dry in the service of others either.

Using purity as a means to control women through Christianity and female genital cutting

By Nicole Mitchell Many communities struggle to accept female sexuality even in today’s modern world. While it is common to see female sexuality in pop-culture, this doesn’t necessarily reflect a universal acceptance. Frequently, a woman’s value is tied to her “purity” or virginity. This prejudice manifests in obvious ways, such as female genital cutting (FGC), and in more subtle ways like teaching women and girls that their worth is tied to their abstinence. These methods of oppression are also not mutually exclusive and occur in many communities around the world including the Western, Christian community. Evangelical America I grew up as a minister’s daughter and one of eight children with five sisters and two brothers. My dad was a minister at an evangelical church in Boston, Massachusetts. While the evangelical movement is considered to be one of the more progressive, modern branches of Christianity, we still subscribed to such beliefs that a woman ought to be submissive to her husband by honoring him as head of the household, church and state. If you were to ask my dad and other fellow religious leaders their opinions on this now, they would probably avoid the question. Over the years, evangelical Christians have softened their voices, particularly in regard to the role of women and the LGBTQ community. This may be attributed to the growing resistance from millennials and younger generations against exclusive ideologies. As a young girl, I was taught that men and women had different, God-given strengths. Examples of female strength focused on traits such as empathy, caring and kindness, whereas male strengths included leadership, power and physical prowess. While men and women could embody both traits, such as being an empathetic leader — I was taught that a woman could never lead over a man. Essentially, the message was that women aren’t really leaders; they can just help organize other women. When I questioned this, I would often have scripture cited to me: “Let a woman learn quietly with all submissiveness. I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet” (1 Timothy 2:11-12). Even more blatantly, “Wives, submit to your own husbands, as to the Lord” (Ephesians 5:22-24). This belief was demonstrated in both my dad’s church I attended and in the larger, global ministry we were a part of, as there were no female head pastors. Women could be guest speakers during services, but never the head of the church. This idea that certain personality traits are reserved for specific genders, specifically leadership and power belonging to men, highlights a deeper division in how communities view a woman’s overall personhood and more specifically, her sexuality. The concept of a person being both spiritual and sexual was never discussed in my upbringing. As a woman, I felt that acknowledging sexuality or sexual desires was in direct conflict with being spiritual; one simply could not be both at the same time. Consummating a marriage was fine, but admitting to having sexual urges was considered not godly (i.e., Christian). Leaders and parents exhibited different attitudes in the way a boy versus a girl would be treated when admitting to participating in sexual acts or behavior. “Boys will be boys,” was the typical attitude when a young man admitted to sexual behavior before marriage. However, if a girl was promiscuous, within the church and my community, there was a substantial attitude of judgement toward her as if she was now deemed unclean, even sometimes suggesting that she was at fault for the boys “mistake” because of the clothes she wore or the way she carried herself. This wasn’t a direct principle preached in sermons; but it demonstrated the way purity and modesty were so heavily emphasized in my childhood. I know my brothers did not experience this emphasis, certainly not to the level I did. For example, every year my mom would take a few of my sisters and I to a women-only conference in New York called PureLife. Women from our global ministry would speak on a variety of topics with a focus on maintaining purity and a “clean spirit” with God. I remember the shame surrounding impurity was a heavy and distinct feeling. It is possible to surmise that when an idea is subtle or silent, it becomes more powerful because it is more difficult to challenge. This purity prejudice was further backed by scripture. One of the most fundamental stories in the Bible about Adam and Eve, instructs that mankind was doomed due to a woman pursuing knowledge. Eve’s interest in the tree of knowledge is portrayed as her ultimate downfall. Much like I would have been disgraced for exploring my sexuality at a young age, Eve was banished from heaven for pursuing knowledge according to the story. One could even surmise that the Bible is alluding to sexuality, not knowledge, given the level of shame Eve received. This idea that a woman should suppress her knowledge or sexuality is seen clearly in another important story in the Bible. The birth of Jesus Christ comes quite literally from a virgin mother. In theory, this teaches that the “ideal woman” would never explore her sexuality. After all, the “savior of the world” came from a “sexless” and “pure” woman. A woman pursuing her own sexuality or knowledge is not encouraged, but rather a sin. The Bible as it was written by men over time has a unique ability to reward submissive behavior, while inciting fear in women who might explore their own body. As a young Christian girl, it was clear my role model was to be Mary and not curious Eve. Again, while these principles were not overtly stated in the church, they were powerful, nonetheless. Female genital cutting The continuation of female genital cutting (FGC) in the modern world is further evidence of the oppressive undercurrent that defines a woman’s value based on her perceived purity. FGC is often practiced as a way to curb female sexual desires by preventing

Art, Activism, And Healing: Reflecting on our conversation around female genital cutting

By Cate Cox On January 19th, Sahiyo held the webinar, Art, Activism, And Healing: In Conversation Around Female Genital Cutting (FGC). During this webinar, we had the opportunity to hear from four speakers Owanto, Naomi Wachs, Sunera Sadicali, and Andrea Carr about how they have used art as a tool to encourage the abandonment of FGC and to work toward healing. From sculptures to videos and sound bites, this webinar explored how art in all its many forms can be used to uplift the voices of survivors and continue to push the conversation around FGC. Mariya Taher, a co-founder of Sahiyo and U.S. Executive Director, began our webinar by giving the audience an introduction to Sahiyo’s many programs that involve art and activism, including Sahiyo’s Voices to End FGM/C and #MoreThanASurvivor campaigns. Next, our speakers Owanto and Andrea Carr introduced us to their work as career artists, and how they are championing this cause in some of the most prestigious galleries and institutions around the world, as well as in community settings. They reminded us that art can be a tool to spark hard discussions and give people the space to have their own stories seen and heard. Sunera Sadicali and Naomi Wachs helped to expand on that conversation by taking us through their own journeys and explaining the psychological reasons behind why art is such an effective tool for trauma healing. The insight and experience of our panelists not only helped our audience to understand what has been done in the field of art and activism surrounding FGC, but stood as an inspiration for how we all can engage in art and activism in our own personal lives. At the end of our webinar, our audience had the opportunity to ask our panelists questions about their experience and knowledge. The questions explored how our panelists were able to get people to open up about their experiences with FGC and how they were able to use art to encourage education and conversation around this issue. Coming from their multi-disciplinary backgrounds, each of our panelists were able to speak to a unique aspect of these questions. Despite their diversity of experience, they each emphasized the importance of art as a conversational medium, that allows people to take control of their own narrative, and when a safe space is created, encourages healing. Art, Activism, And Healing: In Conversation Around Female Genital Cutting (FGC) explored the often underutilized tool that is art to empower communities to abandon FGC and support survivors’ healing. It reminded us that activism and healing take many forms, and that, as Owanto said, “There is light.” For those who are interested in learning more about art and activism, Sahiyo is hosting a screening of our Voices to End FGM/C videos coming up this February. You can register here to attend! If you were unable to attend this webinar, or would simply like to learn more about this event, the transcript and recording of this event are attached below. Watch the recording of this event. Read the transcript.

Art, Activism, and Healing webinar: In Conversation Around Female Genital Cutting

By Cate Cox Across the world, millions of women and girls are at risk of female genital cutting (FGC). FGC can have severe physical and psychological impacts that last a lifetime. As the painful effects of FGC are brought to light more and more, activists and therapists alike are looking for more ways to support survivors and protect future girls from this practice. Art is an underutilized tool to create awareness about this issue and support survivors’ healing. As an organization whose mission is to use storytelling to empower communities to abandon FGC and support survivors’ healing, Sahiyo is one of the key advocates for utilizing art as a means of supporting these effectors. From the Voices To End FGM/C campaign, the #MoreThanASurvivor collages, and the Faces for Change project, art and activism have long been part of Sahiyo programming. On January 19th, 10 a.m. EST, Sahiyo will be hosting the webinar, Art, Activism, and Healing: In Conversation Around Female Genital Cutting. During this inspiring event, you’ll hear from four expert panelists, Owanto, Andrea Carr, Sunera Sadicali, and Naomi Wachs, as they discuss art and its role in supporting survivors’ healing, how activists and survivors alike can use art to make a change in their communities, and working toward prevention efforts to end female genital cutting. Following the vein of one of our previous webinars, Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing, the speakers will first introduce their work and their personal journeys related to this subject and then we will have a question and answer session led by Sahiyo co-founder Mariya Taher. To hear more about how art can help you as a survivor and/or an activist, please register for the event. This event is open to anyone who wishes to attend. Register Today: https://bit.ly/ArtActivismAndHealing Owanto is a multi-cultural Gabonese artist born in Paris, France. She was raised in Libreville, Gabon, and later moved to Europe to study philosophy, literature, and languages at the Institut Catholic de Paris in Madrid, Spain. Her multidisciplinary practice emerges from a 30-year career where she explores a variety of media, including photography, sculpture, painting, video, sound, installation, and performative works. Her practice enables her to engage with consciousness through the notion of memory, both personal and collective. Andrea Carr has worked across a broad spectrum of the performing arts, bringing vitality to global ecological and social themes. Embracing change along the way, her work often distills into designs that move between art installations and immersive environments. Her work has been included in the U.K. representation of the World Stage Design Exhibition, in the Aesthetica Art Prize anthology, and in the ‘Designers Lead’ section of the Society of British Theatre Designers (SBTD) 2019 exhibition at the V&A. Andrea is also studying Process Orientated Psychology. She works from her Peckham Studio, her ‘dream palace,’ where she goes to ground her ideas, make models and mock-ups, and as a space for collaboration. Sunera Sadicali was born in 1982 in Mozambique and later moved to Lisbon. She grew up in a family that was part of the Bohra Community; they were (and still are) the only members in Portugal/Iberic Peninsula. She underwent female genital cutting, or khatna, at the age of 8 in Pakistan, while visiting her grandparents on vacation. She moved to Spain to study medicine at the age of 19 and finished her Family Medicine residency in Madrid. Since 2015, she has lived and worked in the south of Sweden with her partner and three lovely kids. She has been politically active since the birth of her second child in 2012, with a focus on women’s issues, decolonial feminism, anti-racism, and healthcare activism. Naomi Wachs has a B.S. in Theater from Northwestern University and a Masters in Social Work (A.M.) from the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration. While at S.S.A., her concentration was in clinical social work with a focus on art-based methods, LGBTQ affirmative practice, and trauma-informed practice. From 2015-2017, as a German Chancellor Fellow with the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation under the guidance of Tobe Levin von Gleichen, she explored art-based practices as a tool for trauma healing and restorative dialogue with immigrant and refugee communities affected by FGM/C and other forms of gender-based violence. Currently, Ms. Wachs is a psychotherapist at Connections Health in the Chicagoland area where she works with individuals, couples, families, and groups with anxiety, depression, trauma, eating disorders, and relationship and identity concerns. This event is sponsored by Sahiyo.

Reflection on Addressing FGC in the Clinic: A Dialogue between Survivors and Healthcare Professionals

By Sandra Yu On December 8th, 2020, Sahiyo hosted a webinar featuring several health professionals and survivors of female genital cutting (FGC) to discuss the necessity for trauma-informed care and cultural competency. The event was an eye-opening and invigorating conversation as the panelists discussed the failures of the current medical system and necessary next steps to improve systemic care for survivors of violence. Renee Bergstrom and Sarata Kande, two outspoken advocates against FGC, provided unique and moving perspectives about how cultural competency and vulnerability are key to providing better care. The juxtaposition between their Voices to End FGM/C videos and their spoken statements on the panel about their past experiences with healthcare professionals was truly powerful. “Once it’s done to you, you are forbidden to ever mention it to anybody,” Kande said. “But when you share your story, it feels good.” In response, Deborah Ottenheimer, M.D., detailed how she identifies and speaks with survivors of FGC in an inclusive, vulnerable, and caring manner. Karen McDonnell, Ph.D., a public health specialist and creator of the The George Washington University FGM Toolkit, also addressed the critical need for providers to learn about FGC from a public health perspective, expanding on the treatment of FGC as a subsector of gender-based violence. Mariam Sabir, a Sahiyo volunteer and 4th-year medical student, gave an unsettling glimpse into the current state of medical education surrounding FGC as she described her interactions with peers and faculty on the topic. The central theme that arose was the importance of communication, whether it’s between healthcare providers, communities, the general public, or patient-doctor interactions. McDonnell speaks to the creation and normalization of the language used to describe genitalia. Having the right vocabulary to communicate about female genitalia is the first step to having genuine conversations about FGC. Communication between a patient and their doctor is even more crucial for building trust. Knowledge is not enough to make a person feel safe and comfortable. Bergstrom and Kande alluded to their individual experiences grappling with healthcare providers that fail to embrace vulnerability. Building trust and allowing for vulnerability in the clinic are learned skills that are often overlooked in medical education. The culture of silence surrounding the practice of FGC is pervasive, but we are moving toward a future where silence does not need to be the norm, especially in the clinic where trust is paramount to care. Watch the recording of this event here. Read the transcript here.

Upcoming webinar: Moving Towards Sexual Pleasure and Emotional Healing After FGC

By Cate Cox Female genital cutting (FGC) often comes with a multitude of physical and psychological issues that can impact sexual functioning for many survivors. Yet, oftentimes too little attention is given to these problems. On October 22nd, from 12 p.m.-1 p.m., Sahiyo will be hosting an inspiring webinar about FGC, sexuality, and its connection to mental health. During this webinar, we will hear from three expert panelists: Farzana Doctor, Joanna Vergoth, and Sarian Karim-Kamara, who will help to shed light on these subjects using their professional and personal experiences. Farzana Doctor is an award-winning Canadian novelist and social worker. Her work includes Stealing Nasreen, Six Metres of Pavement, All Inclusive, and her latest novel, SEVEN. SEVEN explores the often complicated relationship between modern and traditional customs, and the struggle to end the practice of khatna, or female genital cutting, in the Bohra community. Recently named one of CBC Books’ “100 Writers in Canada You Need To Know Now,” Farzana’s novels explore complex topics, including loss, relationships, sexuality, gender, and racism. She is also the co-founder of WeSpeakOut and The End FGM/C Canada Network, two organizations dedicated to ending FGC. Sarian Karim-Kamara is a community development worker and the founder of Keep the Drums Lose the Knife (KDLK). She is one of the leading campaigners and activists working to end the practice of FGC, and all other forms of violence against women in the United Kingdom and Sierra Leone. Sarian underwent FGC as a child in Sierra Leone and she has spoken bravely and openly about her own traumatic experiences to help raise awareness. She runs educational workshops for professionals and communities; as well as weekly support groups for survivors of FGC in Peckham, London. She also travels to Sierra Leone to run empowerment and educational workshops aimed at young people and communities. In 2019, Sarian won the Prime Minister’s Point of Light Award. In 2014, she received an award from her Sierra Leone community in London for her service to them as a Community Champion. Joanna Vergoth is a licensed clinical social worker and certified psychoanalyst with 20 years of experience in the field. Throughout her career, she has focused much of her work on healing trauma and advocacy work. Over the past decade, she has become a committed activist to the cause of ending FGC. She first began as coordinator of the Midwest Network on Female Genital Cutting, and recently worked to establish forma, a nonprofit dedicated to providing comprehensive, culturally-sensitive clinical services to women and families affected by FGC, as well as offering psychoeducational outreach, advocacy, and awareness training. To hear from these amazing women please register for the event through the link below. Feel free to grab a beverage or a snack beforehand, and join us for what is sure to be an eye-opening and powerful conversation. This webinar is open to anyone who wishes to attend. Register here: https://bit.ly/HealingAfterFGC This event is co-sponsored by Sahiyo, WeSpeakOut, End FGM/C Canada Network, forma, and Keep the Drums Lose the Knife.

On the path to healing: My journey after experiencing female genital cutting

By Anonymous Country of Residence: United States Every woman that has been cut has a story to tell. I tell my story not to offer a universal account of female genital cutting (FGC), but one that is specific to me. At a young age, I underwent Type II female genital cutting, known specifically as “taharah” (purification) within the Egyptian community, in which only part of the clitoral hood was removed and partial removal of the labia minora/majora. The taharah took place in Cairo, Egypt, while visiting relatives. This was the second time I visited my parent’s homeland. My parents were unaware, or at least this is what I’d like to believe, of what had occurred, as my sister was in a coma at the time and her prognosis was poor. They agreed that I travel to their homeland with my auntie to avoid the negative effects of witnessing what my sister was going through. My aunties had convinced me that this was a rite of passage, and what I was about to embark on would make me a “woman.” One week after arriving in Cairo, my auntie took me to a medical office where a doctor performed the surgery. She remained in the room while I underwent FGC, while my other auntie waited by the phone to hear the “good news.” I have no recollection of the surgery, as I was under anesthesia. However, I awoke to excruciating pain that would last for weeks. I remember my family members visiting to celebrate—bearing money and gifts. Upon returning home my parents realized that something was different about me. Already small-framed, I had lost ten pounds. I notified them of what occurred, and I remember them speaking with my aunties. However, the details of the discussion were unknown to me. In 2001, while taking a women’s psychology course, I learned that FGC was considered a human rights violation. Students in the class, including those from countries where this was practiced, were surprised and “disgusted” that FGC continued to be practiced. I was taken aback, as I had assumed this was a custom that many practiced. I began opening up to female friends from similar and varying backgrounds. I quickly discovered I was alone in having had it done to me. I started looking into the practice of FGC and found that there were many factors contributing to the perpetuation of FGC. Some linked it to geographical location, religion, customs, sexuality, marriageability and education. I realized this was a complicated custom that could not simply be thought of as being continued by “ignorant” people. In fact, much of my family are college educated, wealthy, and progressive in terms of religion, and advocate for the rights of women. However, the reasons given for its continuation had been rationalized by them and somehow given cultural significance. I needed answers, and began a long journey that would ultimately lead to my decision to become a social worker, and work with women who have also been cut. Mapping the Healing Journey I was left feeling extremely confused, particularly as most of my family had decided to discontinue the practice due to religious reasons (stating that FGC is “haram” or a sin, and is not a “sunnah” or religious obligation. I searched for answers—or perhaps a place where I would feel accepted and learn to accept myself. I immediately reached out to gynecologists, gender violence organizations, and social workers. Much to my dismay, all were unaware of the FGC practice. Gynecologists stared blankly at my genitals stating, “At first glance, it looks intact.” However, they were unsure the extent of the “damage” done. Gender violence organizations stated that they dealt with different forms of gender violence. “This isn’t something we specialize in,” I was told. They referred me to organizations that had more familiarity. However, they were located overseas. Social workers were unfamiliar with the practice but verbalized their strong beliefs about it. They reacted with words such as “disgusting,” “barbaric,” and “horrific.” They “encouraged” and “empowered” me to advocate for change against the oppressive practice that they assumed was justified by Islam and patriarchal oppression. They also questioned the reasons that parents would allow for such a thing to happen to their little girl. This was extremely difficult to hear given my close relationship with my parents. I walked away feeling judged, ashamed, and defective. For the first time, I began to experience symptoms of depression, which led me to become more embarrassed and secretive about what had occurred. Approximately eight years later, while reading a newspaper article, I came across the name of a Sudanese woman who started a grassroots organization for women who have been cut. The only experience I knew was one in which providers gawked at me when I told them what had occurred. I reached out to this woman, and she invited me to dinner to speak on a more personal level. Upon arriving to the restaurant, I was greeted with a warm smile. For the first hour of our meeting, she did not bring up the conversation of FGC. Surprised, I inquired, “So are we going to talk about… you know.” She replied, “When you’re ready, I am here to listen.” For the first time in a long time, I felt acknowledged, understood, accepted, and supported. We all begin our journey of healing somewhere. I am delighted to be a part of the Sahiyo team—and truly look forward to being a part of the healing process for others.

Wrestling with trust and fear in regard to female genital mutilation

By Farzana Esmaeel Country of Residence: United Arab Emirates Trust and fear are two emotions that have an interesting correlation to input and output of human behavior. One emotion, trust, establishes safety and comfort for individuals whilst the other, fear, displaces the very premise of safety and comfort. At the age of 7, you don’t articulate emotions; you feel them. And your mother is your beacon of trust. She loves you, comforts you, cares for you and sacrifices for you. Then, when trust is removed, it’s only natural to feel extreme pain and deceit at her hands the most. My sister and I were taken to a dilapidated, dimly lit building at the far end of the city on the pretext that we were going to meet an aunt for a check-up. At the tender age of 7 when mum tells you we are going for a check up you don’t appreciate entirely its meaning, and at the time it meant to me that we were going to see a doctor. What followed was unprecedented, and a memory that will be etched in our minds forever. Sadly. The pain was too much to bear as 30 years ago, female genital mutilation (FGM) in the Dawoodi Bohra community was generally more practiced under callous and less “sterile” ways. (Yet, even today, when it is practiced by licensed white coat doctors under more hygienic conditions, it doesn’t make the practice correct.) The overarching feeling I took after my experience 30 years ago was deceit. My mother is a simple, non-confrontational, less informed person, who at the time of my sister and my cutting, played into the hands of a community (mindset) that propagates fear: fear of being ‘ostracized’ for not having FGM done, fear of her daughters being ‘impure’, fear of standing up against cultural norms and practices. Though today, this same woman hasn’t once told either of her daughters to carry out this inhumane practice on her granddaughters. She now understands the pain and futility of it all. FGM is a practice entrenched with ‘fear,’ stripping human ‘trust,’ and inculcating in young girls early on to be apologetic about their sexuality and their desires. It is on us to be the change. We must question this violation of human rights and ensure that we raise our voices against this harmful practice, not just for our daughters, but the many more daughters all around us.

A mother’s side of the story on female genital cutting

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography, and writing. She is currently conducting research on the individual experience of khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series: Khatna Research in Mumbai. The proverb, “It takes a certain courage to raise children,” rings true, especially since much of the responsibility for a child’s development rests solely on the parental system. The parents significantly influence a child’s development, since the social connection formed with them serves as the prototype for all their future interactions. Through this parental interaction, the child learns values, traditions and learns to understand the culture. Within the cultural context of India, much of this responsibility shifts onto the shoulders of the mother. Due to the proximity and consistent presence of the mother, the child is naturally attuned to her and views her as their primary caregiver responsible for providing love, warmth, and protection. Any adversity experienced by the child may be seen as the mother’s inability to fulfill her responsibilities. Similarly, in the case of khatna, which is a custom among the Bohri Muslims in India which involves partial or total removal of the clitoris, girls may subconsciously blame their mother for failing to “protect” them, although women understand that culture and tradition are responsible for the pain they experience. In my own research, when I conversed with participants I found that even when another female member takes them to be cut, the blame rests upon the mother alone. Initially, I found myself puzzled on this discrepancy in attribution. But during in-depth conversations with my participants, I found that all of them “trusted” their mothers to love them and to protect them. They stated that their mothers had “broken my trust” by continuing a practice without even attempting to understand its implications. Thus, the participants were angry because they had been betrayed. This experience has been discussed significantly in other research, as well. However, I wondered about the kind of emotions elicited in the mothers who were at the receiving end of their daughter’s anger. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to talk to mothers. Through conversations with them, I found that even the mothers have been significantly impacted by the revelation that they had done wrong to their daughters. From a mother’s perspective, her world is crashing down as well. Through all these years she has developed a belief that khatna is good. It may make her daughter belong to their community. it may keep her safe. She acts on this belief with good intentions of protecting her daughter and doing what she believes is her motherly duty. As her child grows up, she does many such acts with good intentions to protect and love her daughter. Throughout her life, the mother forms the belief that I am a good mother who has checked off all the boxes. Several years later, she may find herself in a situation where she is now bearing the brunt of her daughter’s anger because she has failed to protect her child from harm, particularly of khatna. This revelation shatters a belief in khatna she may have fostered for more than half of her life. In therapy, we always say that beliefs are the most difficult psychological construct to work with because all beliefs are interconnected. These interconnections form the self of a person. When one belief is broken, it causes a chain reaction where the other beliefs begin to be questioned. The same happens with a mother. Post-revelation she begins to question every aspect of her life, her identity, and her essence. A mother may then feel an overwhelming sense of failure and inadequacy. Biologically speaking, whenever we are overpowered, our fight or flight responses kick in. Therefore, the mother may respond to her pain with anger and denial. It is helping her keep her sense of integrity intact. When the mother responds in anger and denies having done anything wrong, the impact it has on the survivor is severe It heightens her emotions. It’s important to remember that both the mother and the survivors are fighting their own battles. Both parties need time to process this shock. Thus, it is essential that the space for change is provided by both sides. Some of the pointers to remember during this time that are applicable to both the survivors and the mothers: Remain empathetic. Both of you may be struggling. Be kind. Do not raise your voices while talking. Do not accuse each other. Listen when the other person talks. Both of you have the right to say your part. Have conversations outside the purview of khatna. Establish some routines with each other: eat together or go for walks together. Respect each others’ decisions. The dynamics of a relationship are bound to change once such an intense conversation takes place. It is essential that during this time of transformation, a sense of support for each other is established. At the same time, it may be difficult to do so, but it is imperative that this be done if the new dynamics are to mimic the love, warmth, and comfort that may have been present in the previous relationship. My participants themselves mentioned that although the dynamics between them and their mothers have changed, with time and space their bond has only become stronger. A message to the survivors, you have the right to be angry. You have the right to be heartbroken. Give yourself time to feel all these emotions. Take care of yourself. Access some helpful resources. For mothers who regret their decisions but do not know what to do, apologizing always helps. Not only would it heal you, but it may heal your daughter, as well. For mothers in the dilemma of whether they should perform khatna on their daughters, please don’t do it. A life full of pain and regret is no way to live, neither for you