Using purity as a means to control women through Christianity and female genital cutting

By Nicole Mitchell Many communities struggle to accept female sexuality even in today’s modern world. While it is common to see female sexuality in pop-culture, this doesn’t necessarily reflect a universal acceptance. Frequently, a woman’s value is tied to her “purity” or virginity. This prejudice manifests in obvious ways, such as female genital cutting (FGC), and in more subtle ways like teaching women and girls that their worth is tied to their abstinence. These methods of oppression are also not mutually exclusive and occur in many communities around the world including the Western, Christian community. Evangelical America I grew up as a minister’s daughter and one of eight children with five sisters and two brothers. My dad was a minister at an evangelical church in Boston, Massachusetts. While the evangelical movement is considered to be one of the more progressive, modern branches of Christianity, we still subscribed to such beliefs that a woman ought to be submissive to her husband by honoring him as head of the household, church and state. If you were to ask my dad and other fellow religious leaders their opinions on this now, they would probably avoid the question. Over the years, evangelical Christians have softened their voices, particularly in regard to the role of women and the LGBTQ community. This may be attributed to the growing resistance from millennials and younger generations against exclusive ideologies. As a young girl, I was taught that men and women had different, God-given strengths. Examples of female strength focused on traits such as empathy, caring and kindness, whereas male strengths included leadership, power and physical prowess. While men and women could embody both traits, such as being an empathetic leader — I was taught that a woman could never lead over a man. Essentially, the message was that women aren’t really leaders; they can just help organize other women. When I questioned this, I would often have scripture cited to me: “Let a woman learn quietly with all submissiveness. I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet” (1 Timothy 2:11-12). Even more blatantly, “Wives, submit to your own husbands, as to the Lord” (Ephesians 5:22-24). This belief was demonstrated in both my dad’s church I attended and in the larger, global ministry we were a part of, as there were no female head pastors. Women could be guest speakers during services, but never the head of the church. This idea that certain personality traits are reserved for specific genders, specifically leadership and power belonging to men, highlights a deeper division in how communities view a woman’s overall personhood and more specifically, her sexuality. The concept of a person being both spiritual and sexual was never discussed in my upbringing. As a woman, I felt that acknowledging sexuality or sexual desires was in direct conflict with being spiritual; one simply could not be both at the same time. Consummating a marriage was fine, but admitting to having sexual urges was considered not godly (i.e., Christian). Leaders and parents exhibited different attitudes in the way a boy versus a girl would be treated when admitting to participating in sexual acts or behavior. “Boys will be boys,” was the typical attitude when a young man admitted to sexual behavior before marriage. However, if a girl was promiscuous, within the church and my community, there was a substantial attitude of judgement toward her as if she was now deemed unclean, even sometimes suggesting that she was at fault for the boys “mistake” because of the clothes she wore or the way she carried herself. This wasn’t a direct principle preached in sermons; but it demonstrated the way purity and modesty were so heavily emphasized in my childhood. I know my brothers did not experience this emphasis, certainly not to the level I did. For example, every year my mom would take a few of my sisters and I to a women-only conference in New York called PureLife. Women from our global ministry would speak on a variety of topics with a focus on maintaining purity and a “clean spirit” with God. I remember the shame surrounding impurity was a heavy and distinct feeling. It is possible to surmise that when an idea is subtle or silent, it becomes more powerful because it is more difficult to challenge. This purity prejudice was further backed by scripture. One of the most fundamental stories in the Bible about Adam and Eve, instructs that mankind was doomed due to a woman pursuing knowledge. Eve’s interest in the tree of knowledge is portrayed as her ultimate downfall. Much like I would have been disgraced for exploring my sexuality at a young age, Eve was banished from heaven for pursuing knowledge according to the story. One could even surmise that the Bible is alluding to sexuality, not knowledge, given the level of shame Eve received. This idea that a woman should suppress her knowledge or sexuality is seen clearly in another important story in the Bible. The birth of Jesus Christ comes quite literally from a virgin mother. In theory, this teaches that the “ideal woman” would never explore her sexuality. After all, the “savior of the world” came from a “sexless” and “pure” woman. A woman pursuing her own sexuality or knowledge is not encouraged, but rather a sin. The Bible as it was written by men over time has a unique ability to reward submissive behavior, while inciting fear in women who might explore their own body. As a young Christian girl, it was clear my role model was to be Mary and not curious Eve. Again, while these principles were not overtly stated in the church, they were powerful, nonetheless. Female genital cutting The continuation of female genital cutting (FGC) in the modern world is further evidence of the oppressive undercurrent that defines a woman’s value based on her perceived purity. FGC is often practiced as a way to curb female sexual desires by preventing

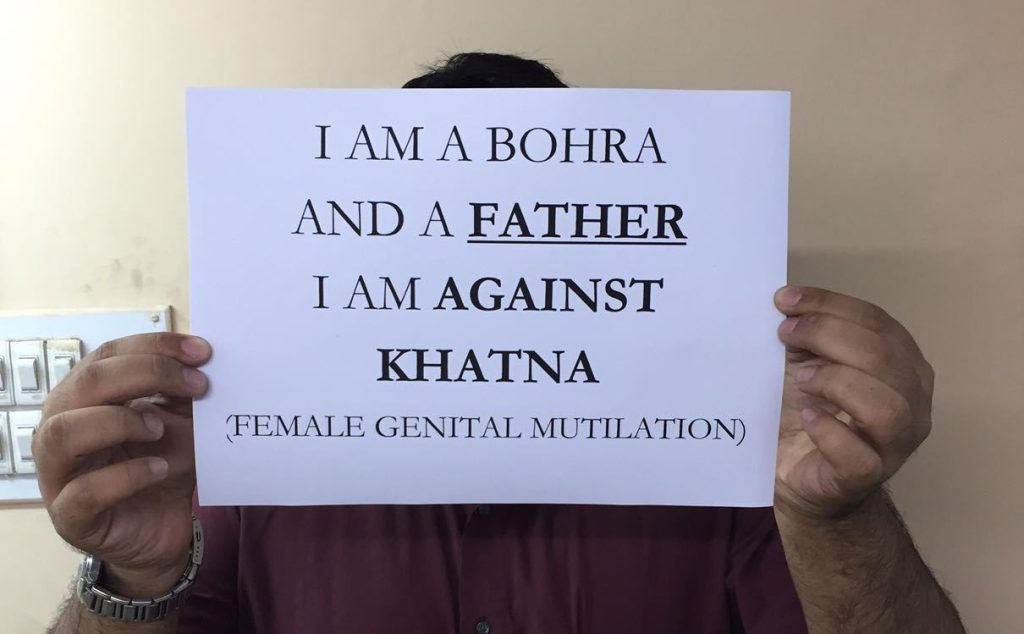

Rejection of khatna must be a step in the liberation of Bohra women

By Zarina Patel Khatna, or female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) within the Dawoodi Bohra community, is not a distinct or unique ritual. It has a context and it is important that Bohra women (and men) understand that context if they are to free themselves holistically, not only from the ritual itself, but from all that promotes it. Khatna is an imposition of a patriarchal system, a male-controlled system, that seeks to assign a gendered role or designated place for women and imposes rules and regulations to maintain these assigned roles. For women, that role is strictly within the family unit where her duty is first and foremost that of caring for her family, especially the husband or parents; giving birth, including ensuring the survival of humanity; nurturing the progeny; and upholding and promoting this culture and these customs which are largely defined by the patriarchs. No boy child has his destiny mapped out at birth within the Bohra community, but the idea of a girl child choosing and planning her destiny is considered as entirely secondary and trivial to her so-called God-given role. In this era of the internet and women’s liberation globally, it has seemingly become even more imperative for the patriarchs to keep their women (who, of course, they may consider as their property) in their place. Nothing works better than religious persuasion, but it so happens that nowhere in the Holy Quran is khatna mentioned, let alone made mandatory. So the patriarchs have concocted a variety of restrictions: women’s dress code is ordained for them; the baggy and unsightly rida is designed to make them feel ashamed of their bodies and to limit their movements; if women must work outside the home, it has to be in family circles or at most in a Bohra environment; if widowed, she must observe total seclusion for four months; associating or travelling with strangers is frowned upon, and so on. Khatna confers absolutely no benefit, medical or moral, to the girls who are cut. It can be traumatic with long-lasting effects both physical and psychological. It is one more such tradition, which at a very young age instills into the girl child that she is tainted and impure, and hence, it is normal for her to be violated and controlled. Is it surprising then that as adults, most Bohra women meekly accept the various restrictions placed on them. But women are the greatest defenders of the practice, we are told. True, very true – and some of those women are doctors and the like, educated, so to speak. Sahiyo has done, and is doing sterling work in exposing the harmful practice of khatna, and encouraging opposition to it. The rejection of khatna must be a step in the liberation of Bohra women.

An ode to every woman fighting social norms around the world

By Geethika Kodukula Country of Residence: USA (This month, Indian news reported three disturbing incidents targeting women and girls. In the first, 68 students at a women’s college in Gujarat were forcibly strip-searched to prove they were not on their period because the college’s religious administration does not allow menstruating women to enter temples or kitchens or even touch other people. Days later, female college students in Maharashtra were forced to take an oath that they would never marry for love — instead, they would only marry husbands chosen by their parents. In a third shocking incident, 10 women applying for a government job in Gujarat were stripped and subjected to a “two-finger test” to check for pregnancy. This essay is a cry of outrage against such acts of oppression in the name of social norms; it is an ode to women all over the world, who are forced to fight the norms of patriarchy every day in order to simply survive.) What makes a woman? Is it her kindness, generosity, friendship, ability to work for a living, or take care of her family? Men can do all these things just as well. But a woman can give birth, while a man cannot. We revere this ability, celebrate it and encourage girls to want it for themselves. But not on their terms. We want to control it and shepherd it. At an age when girls have no idea of sexuality or reproduction, we invade their bodily boundaries in the name of purity and tradition to cut their genitals. We call it khatna, sunnah, khafz, female circumcision, and practice it in more cultures around the world than we’d like to admit. We do this to our daughters in spite of the physical and psychological pain it caused us, ourselves. Girls and women who have undergone the procedure tell us that it does more harm than good. At an age when biology decides that she becomes a woman, we likely celebrate menarche, the first period. In many cultures, we make a fuss, invite people over to bless our little girl who can now bear children and buy her new clothes, jewelry, and gifts. But she’s shocked at the blood between her legs. All her life, television commercials have shown the liquid that goes on pads and tampons as a soft blue. What is this business with blood? Is she dying? We don’t talk about that. We call the process various euphemisms. We treat these girls as impure, make them sit and sleep separately, wash their clothes and any bedding they may have touched, and essentially quarantine them every month because of this “curse” that gives us the “blessing of a child.” We may subject her to strip searches in an institution dedicated to education, no less, to prove that she is not bleeding and can, therefore, sit, eat and mingle with her friends. What is at threat of being stripped is her dignity, which we say we value the most. We treat nearly grown adults as impure, untouchable, and stigmatize and hide all of it from the males in the house. Imagine the anxiety and resentment these young women may build toward their bodies over a completely normal biological phenomenon. We speak to females in hushed tones about how to dispose of evidence and pretend as if nothing changed. If a woman cannot give birth due to any reason (choice being the least respected one of them), we worry, berate, label, and shame them. There is no pleasing us. We don’t want her to look at or talk to boys for the first twenty years of her life. Then we want her to magically know how to live with a man and anticipate his wishes and whims. We want young schoolgirls to formally pledge that they will not marry for love. Let’s consider that. Even if a woman found another human being she considers compatible and wants to spend her life with him, she should reject him and marry a stranger selected by her parents based on the family he was born into, his religion/state/caste/creed, occupation, and the family’s assets and holdings. How many of these things have a real bearing on the partner he will be? Let’s say she does marry the male her parents chose for her. What if her husband or his family wants to test her “virginity”? There are sects in India who take this very seriously. Amazon sells a product to fake your way into being a virtuous bride if you are one of the millions of women whose hymen tore while bicycling or dancing. Or if you didn’t bleed profusely the first time you had sex because–to borrow an idea this HuffPost article offers–the hymen is not a plastic wrap stretched over the Tupperware of your virginity. Imagine the disorientation this young girl may experience after being shamed and humiliated for intercourse she may not have had. We urge newlyweds to get busy. We urge the woman to not put her career before her family and have many children. Television and movies keep showing childbirth as a briefly excruciating, but ultimately, a gratifying experience. No one says anything about postpartum complications, anxiety, or depression. Millions of people watch the Oscars but an ad about new moms’ preparedness will never reach our women since it was rejected by ABC to air. In her homestead our woman lives as happy as one can be in her place in society. But according to Krushnaswarup Dasji, she cannot cook for her family for five days a month, (longer if she has reproductive issues). Her husband’s family never got around to teaching him how to cook. This is a dilemma, indeed. Her husband and sometimes her children resent her for making them eat take-out. As she enters menopause, she is viewed as less useful than she was, no longer able to bear children. Having lived a life carrying back-breaking gender norms, she dies to finally be at peace from societies’

The complexities of female genital cutting (FGC) in Singapore: Part III

Tradition and patriarchal elements of FGC By Saza Faradilla Country of Residence: Singapore This blog post is the third in a four-part series about female genital cutting (FGC) in Singapore. This third installment explains some of the reasons the interlocutors provided for practicing FGC, including tradition and the control of female sexuality within patriarchy. Read part one here. Read part two here. Reasons for FGC: Tradition Many of my interlocutors allude to adat or Malay tradition when asked for reasons they practice FGC. They view it as a normalised and long-established cultural tradition, which is often performed without question. There are also some interviewees who believe this leads to the unity of the community and is intrinsic to the Malay identity. However, those who are unsupportive of FGC question the premise of this tradition and that if there is no rational or logical reason behind it, “it doesn’t make sense to blindly follow it.” According to Gabriele Marranci, “FGC is transmitted generation after generation as an ordinary act of Malay Muslim identity. It can be considered an integral part of Malay Muslim birth rituals and is linked to a specific Malay Muslim identity. Malay Muslims often say, “We do this because it is our tradition. It is something that all Malay Muslims share both here in Singapore and in Malaysia.” Indeed, many of my interlocutors also agree that this practice has been very much normalised in Singapore. “This is tradition: sisters, granddaughters, daughters all do it, said Fauziah, an interviewee. “This is a strong Malay tradition, we can encourage it, but don’t force. It’s a natural next step.” This tradition is usually passed down a matrilineal lineage, with the grandmothers and mothers of the family encouraging and sometimes even forcing their children to cut their granddaughters. This could be due to the division of labour in Malay families, where women usually take care of matters concerning the children’s development and well-being, while the father provides the economic means to raise them. As such, many men would leave the decision-making regarding the execution of FGC to their wives. They might not even want to know anything about it. It is considered too insignificant for fathers to have a stake or say in the issue. However, those who are against FGC view the unquestioning nature of this practice as symptomatic of a larger problematic trend of traditionalism within the Malay community. “People do not question or discuss this, and it is a problem that it is not critically discussed,” said Ermy, another interviewee. “People just do it blindly, and so this might cause harm and injury.” Many Malay families continue this practice in an inadvertent manner, and one that is continued not because it is “actively better” but because it is just not worse. As such, FGC is simply passed down and accepted rather than its rationale being questioned or challenged. At the same time, I noticed that amongst those interviewed, younger people (around the ages of 20-40 years old) are unwilling to perpetuate FGC if the sole reason is tradition. “If it’s just based on tradition, it doesn’t make sense to do something like that,” Hanisah, a 38-year old teacher, said. “Culture is not important to keep if it is causing pain.” Many younger Malay Singaporeans do not view FGC as something that possesses active benefits, and therefore, they do not see the point or logic in continuing it. Control of female sexuality within patriarchy Seven out of my eight interlocutors who support FGC readily admit that the cut is important to control women’s sexuality. According to them, FGC is to “cut down on the girl’s sexual desires (nafsu).” They suggest that “by nature, women have a higher sex drive, and so this is to lower chances of sex before marriage.” When asked to explain precisely how FGC leads to lowered sexual desire, or how this relationship can be measured, most interviewees are uncertain. In fact, I had a rather drawn-out conversation (complete with drawings on both our ends), about how the removal of the clitoral hood actually reveals the clitoris more, and so that logically follows that it is more easily stimulated, and therefore, might lead to higher sexual satisfaction. Even though supporters of FGC might be unsure how FGC affects sexual desire, the principles they hold for that view is important to acknowledge. Believing that FGC is important to control female sexuality might be reflective of the prejudices and biases against women in the Malay community. These traditional values may have arisen because women are traditionally seen as the bearers of morality in societies. As such, it is important within the Malay community to ensure that women uphold important societal values and any potential for deviance is weeded out as soon as possible. (The fourth and final installment will provide an analysis and concrete methods of engaging with discourses on FGC at the individual, community, governmental and international levels.) Saza is a Senior Executive of service learning at Republic Polytechnic in Singapore. She recently graduated from Yale-NUS College where she spent much of her college life developing her thesis on female genital cutting in Singapore. A highly under-researched, misunderstood and personal issue, Saza sought to understand the reasons behind this practice. She ends her thesis by advocating for medical and religious leaders to step up and clarify the fatwas and medical criteria surrounding this procedure in Singapore. Saza is passionate about women’s rights and empowerment and seeks to assist marginalized populations as much as possible.

The complexities of female genital cutting (FGC) in Singapore: Part II

Part II: Cleanliness and religious reasons for FGC By Saza Faradilla Country of Residence: Singapore This blog post is the second in a four-part series about female genital cutting (FGC) in Singapore. This second installment explains two of the five reasons raised by my interlocutors about FGC in Singapore: cleanliness and religion. (Read part one here.) While medical practitioners confirmed that the cut has no effect on cleanliness, Muslim interlocutors believed it still helps with cleanliness, which was pivotal to their religiosity. Religiously, FGC is expounded upon in a hadith (record of the traditions or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), but there have been various interpretations of this hadith. Institutionally, the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) has avoided releasing any official statements on the religious mandate of FGC for the Muslim community. This second installment explains some of the reasons the interlocutors provided for practicing FGC – cleanliness and religion. Reasons for FGC Cleanliness The first reason some interlocutors (especially those who support FGC) shared is that of cleanliness. They believe a part of the vagina traps dirt and needs to be removed, which makes for easier cleaning. To them, this high hygiene standard is particularly crucial for prayer. The evocation of religion is significant here because it shows that my interlocutors actually view religion as the reason for FGC, and that cleanliness happens to fall under that umbrella. However, the practitioner I spoke to disagreed and said that there are no medical benefits to FGC because the “cut is so small, it doesn’t affect anything”. I believe the perceived idea of cleanliness and purity arises out of a misunderstanding of the cut and its specificities (amount cut, area cut etc). Religion According to Amnesty International, “FGC predates Islam and is not practiced by the majority of Muslims, but has acquired a religious dimension”. For most of my interlocutors, their belief in Islam is an extremely important reason for FGC. I will first explore the ways my interlocutors linked FGC to Islam through the evocation of several hadiths and mazhab (Islamic jurisprudence, usually referring to specific Islamic teachers), and then go on to engage with different readings of these hadiths, and also discuss the position that religious authorities and leaders have taken with respect to FGC in Singapore. One of the hadiths that was alluded to by many of my interlocutors is the one told by Al-Baihaqi: “There are a group of people who allow cutting for women by referring to the hadith where Um Habibah was cutting a group of women. On one day, Prophet Muhammad visited her and found a knife in her hand (for cutting). Prophet asked and confirmed that the function of that knife is really for cutting. Um Habibah asked, “Is cutting for women haram (forbidden)?” Nabi (Prophet) Muhammad said, “Oh women of Ansar, do the cutting but be sure to not cut too much.” My interlocutors who support FGC said this hadith provided a clear approval of FGC from Prophet Muhammad, as he did not try to stop Um Habibah from cutting other women, but actually endorsed it. Not all my interlocutors were able to provide exacting details of this account, and they mention the details to varying extents. Most know of this as hearsay. On the other hand, protestors of FGC interpret the hadiths and religious instructions differently. With reference to the same hadith above, Dalia said, “The fact that Prophet Muhammad came across this proves that it was already an Arabic tradition that was pre-Islamic. A lot of things that were already happening, the Prophet did not stop. He was trying to win over the Qurayshi people and so he could not exactly stop them. But the fact that he said to not take much means he already disapproves of FGC”. I was keen to interview someone from MUIS (Islamic Religious Council of Singapore). Although repeated emails to them went unanswered, I found a past fatwa where MUIS strongly endorses FGC as part of the Islamic tradition. “According to the majority of ulama, circumcision is compulsory for men and women. It should be done early in life, preferably when still an infant, to avoid complications, prolong [sic] pain and embarrassment if done later in life. Any good Muslimah doctor can perform circumcision for women.” However, this fatwa was removed from the website in recent years, and MUIS has not since provided a reason for the removal or replaced it with another fatwa. From my research, it is evident that religion is a significant reason for those who practice FGC. Indeed, religion is used to justify FGC around the Muslim world. It is notable that the same hadith is interpreted very differently by both proponents and opponents of FGC. In my concluding paragraphs, I will discuss the policy implications of MUIS taking an ambiguous stance toward FGC and urge them to produce a clear directive. Part III of this series will focus on more reasons for the justification of FGC, including tradition and the control of female sexuality within patriarchy. Saza is a Senior Executive of service learning at Republic Polytechnic in Singapore. She recently graduated from Yale-NUS College where she spent much of her college life developing her thesis on female genital cutting in Singapore. A highly under-researched, misunderstood and personal issue, Saza sought to understand the reasons behind this practice. Saza is passionate about women’s rights and empowerment and seeks to assist marginalized populations as much as possible.

Learning new methods of data analysis to conduct research on female genital cutting

Photo Courtesy Of Pixabay on Pexels.com By Cameron Adelman A major finding of the research project I have been conducting on the social and emotional correlates of female genital cutting (FGC) is that in communities that are more supportive of FGC, there are more reasons to support the practice. Some reasons in support of FGC include the practice as a coming of age ceremony, being promoted by religious/spiritual/community leaders, and being used to preserve a girl’s virginity and to promote her marriageability. Additionally, women are more likely to suffer social and emotional consequences such as having less social support and more negative feelings surrounding the community’s beliefs. In my last blog post, I talked about the conception of my research project on risk factors for female genital cutting and social/emotional issues related to the practice, and the divergence of the project from what I had originally envisioned. The majority of my data and the statistical analyses I ran were from the Demographic Health Surveys Program (DHS). The analysis of the DHS data pointed toward a number of social, emotional, and physical issues that appeared to be more common in women who had experienced FGC, as well as a number of beliefs that were more common in women who had experienced FGC, and some socioeconomic factors that appeared to be related. From this information, I was able to go through my own data and select the information that could help support a working theory of increased stress and emotional concerns for women who had experienced FGC. My data was also helpful for establishing a link between community attitudes and social/emotional wellbeing. My analysis of the data Sahiyo led to a few key findings: First, the number of cultural reasons supporting FGC was positively correlated with how supportive a community is of FGC. With a positive correlation, this means that as one factor increases, the other does as well, so the more reasons a participant selected for why FGC was a part of her culture, the more supportive her community was likely to be of FGC. Second, the number of cultural reasons for why FGC is practiced was negatively correlated with how the community attitude toward FGC made a participant feel. With a negative correlation, this means that as one factor increases, the other decreases. The more reasons a participant selected for why FGC was a part of her culture, the more negatively she felt about her community’s supportiveness of FGC. Third, how supportive a community is of FGC was negatively correlated with how a participant felt about the community attitude, and how many personal sources of support a participant listed that she had available to her. Finally, the number of personal sources of support a participant had was positively correlated with how a participant felt about her community’s attitude toward FGC. Despite the immense help of Sahiyo, I had only 11 participants of my own after sending out a survey to gather data, which was insufficient for a full research paper. This limit is what led me to the DHS. After seeing how significant the findings from the DHS data were it became clear that the best route forward was to take the aspects of my data from Sahiyo members about community attitudes and use that to supplement my findings from DHS. With my data analysis completed, I’ve begun the work of writing the paper that will hopefully be submitted for publication in a research journal at the end of the semester. The results so far suggest unique challenges to supporting women in communities that still actively promote and support FGC. I hope with the work I have done that it can lead to improved services for women in areas both supportive and unsupportive of female genital cutting. More on Cameron: Cameron Adelman is a senior neuroscience major and women and gender studies minor at Wheaton College in Massachusetts. He has been working on his research project about social and emotional effects of FGC since last year. The findings of his research among women who have experienced FGC suggest a number of sociocultural confounds in trying to develop and deliver support systems for women living in practicing communities. Cameron’s hope is to help advise best practices that take these factors, as well as additional risks to wellbeing, into account.

Topple the system- question the microaggressions

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography, and writing. She is currently conducting a research on the individual experience of Khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series – Khatna Research in Mumbai. Patriarchy is that societal system where the head of the family is usually male and the family lineage is determined through the male line. However, this system is much more insidious than that: it invades and corrodes the minds of those who live within it to an extent where they no longer can see beyond their patriarchal identities. It is a system which compels women to not only be coerced into a submissive position but rather stay subdued by distorting the reality to convince them that they are inferior. Thus, I would define patriarchy as a steady corrosion of the feeble minds of young children who are made to believe by society that there exists a hierarchy within the world, in which the man must come first and the woman second. If we are to reflect, we have been indoctrinated into this ideology since our childhood. It is not only a part of our religious scriptures but also has deviously made its way into the stories we tell to our children. Personally, I grew up on stories where women were always the damsel in distress and the prince somehow the elixir to all her problems, whether it was the story of Cinderella or Sita. Growing up, they were my role models, I was supposed to be delicate and compliant, while the men were supposed to be strong and the decision makers, my one-point solution to everything. These stories, these ideas are just the starting point from where patriarchy originates and eventually morphs itself into inexcusable practices such as Khatna – a traditional practice which involves nicking or removal of the prepuce/foreskin of the clitoris. Like Khatna, there are several other patriarchal practices which attempt to curb a woman’s sexuality, like honor killings, acid attacks, and forced abortions, among others. However, considering that these are drastic measures, I wonder: how did we get to this level? Where in the system did we falter to allow for the inception of these measures? The answer lies in our most basic human tendencies. We are naturally bound to dissociate ourselves from anything extreme. Our mind evaluates each incident in the environment for its probability to personally affect us. When anything of moderate intensity occurs, such as cars lightly bumping into each other in a traffic jam, our brain evaluates it as having a high likelihood of it occurring in our daily lives and therefore we are mindful of it, in order to successfully avoid it. Whereas, a car accident on the highway is something so extreme that our mind cannot accept that it can occur to us, and therefore pushes it out, making the individual believe that they would remain unaffected by it. This is how practices like Khatna slip through the radar. We think, “It doesn’t happen to us, we don’t do that in our community”. However, as my feminist friend rightly remarked, “We must then observe and understand the microaggressions that happen within our community which condone and make way for these forms of oppressive practices.” Common examples of these microaggressions are the statements we make to our daughters in passing, “Girls should not loiter; Girls should not wear western clothes as it attracts unwanted attention; Girls should be married early to allow them to have children during their ideal fertile age.” The effects of these statements are profound. They curb a woman’s expression of her sexuality while also absolving the men of any responsibility. I, like many other women, have been personally affected by these microaggressions: for example, while I had to return home by 7 pm, my male counterparts could stay out till 10 pm or sometimes even beyond. I was cleverly indoctrinated to not only choose my clothing according to the occasion but also the accompaniments, I could wear skirts and dresses when in the company of known men because their male bravado was to be my shield of safety. Over time, it is these underhanded comments that fester into erroneous beliefs that I am not enough to protect myself. I truly believe that these underhanded comments breed practices like Khatna, and our naivety in not questioning these statements is how all the misogynistic and oppressive practices continue. An underlying theme found across all these customs is that they are an attempt to control a women’s expression of sexuality, and often like Khatna they are perpetuated by our fellow women. For example, men may indulge in premarital sex but the same luxury is not extended to women, rather since childhood, the piousness of her virginity is drilled into her mind which must be saved for one man alone. How do we topple this system? The first step is to be aware of the system of oppression and the cunning ways in which it works. Then notice its oppressive practices whether they are as minor as your male colleague suggesting that he drops you home because it is very late at night, since a woman traveling with a male companion is much safer than a woman traveling alone at night, or if it is women being disfigured with acid because she said no. Then you rebel against it, not on one level but on all levels. Rebel by asking questions, rebel by asserting your intelligence, rebel by saying no, rebel by coming to the streets, rebel by going to the courts. Don’t let anything extinguish your fire, because we are not the damsels in the distress this patriarchal society painted us to be. We are the warriors they were afraid of, and we are here to take back what rightfully belongs to us.

Why men too must speak out against Khatna

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography and writing. She is currently conducting a research on the individual experience of Khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series – Khatna Research in Mumbai. Khatna, by virtue of being related to female anatomy, is often categorized as a women’s issue. However, one must also remember that it is a practice performed on uninformed and unconsenting children. We must move beyond defining it as a child or a woman being violated and look at it as a human being who is being wronged, and therefore the most comprehensive way to describe it would be a human rights violation. Despite it being a human rights issue, it appears as if not many people are willing to speak up against it, even though all people, especially men, need to do so. Within the structure of the Indian patriarchy, men enjoy power not only by virtue of their gender but also by their sheer number in our country. Therefore men can use their position of power to effectively tilt the weights in favor of women who are speaking against Khatna. Although, ideally we expect all men to support us in the endeavour to end Khatna, we should also attempt to understand their hesitancy. Within the Indian patriarchal family structure, the woman is seen as the mistress of the house, in charge of children, while men are seen as masters for all things outside the domain of the house. Therefore any attempt by men to venture into the discussion concerning women’s bodies is seen as ill-mannered and a gross violation of clearly demarcated gender roles. During my research, I met a father who became aware of Khatna and its consequences because he had daughters and therefore vehemently opposed it. He narrated the daily struggle of convincing his own mother against this practice. However, like many other men before and many after him, he was unsuccessful in dissuading the women in his family from continuing it on his daughter. He was blindsided by his mother and given the blanket argument that she knows better for a woman by virtue of herself being a woman. Yet research has shown that with increasing education on khatna, more men are willing to campaign against it. Still, the onus of initiating a conversation on khatna among others lies with the women. Communication between men and women, especially husband and wife, is crucial for the discontinuation of Khatna. A woman I interviewed who had undergone Khatna took this initiative and began a conversation with her husband, which gave her immense strength and helped her protect their daughter from falling into the clutches of tradition. Research too corroborates the same: if more men are are part of the decision making process, the less the likelihood that Khatna would be performed on the girl. The research linked above shows that men who wish to speak up are held back by their limited knowledge on the effects of Khatna.They are unaware of what is removed and what its ramifications are. The primary reason for this ignorance is the lack of conversations about women and their health among family members. This hesitancy to talk about women in front of men comes from the idea that women are equivalent to the family’s honour, therefore talking about aspects of their sexuality may be seen as a violation, thereby a disgrace, to the family’s honour. However, we must move beyond the archaic concept and understand that creating awareness about the ill effects that Khatna has on a woman’s body in no way defiles a family’s honour. After all, what honour can reside in pain? Conversations about Khatna must begin, questions must be asked and collaborative measures between men women must be taken to put an end to this practice. There are several ways to oppose this practice. You may choose to speak out or you may to choose to silently protest; however, if active measures are not taken to resist it, then there is passive consent for the continuation of khatna, and we must understand that every time such consent is given, it means another child is being harmed. Therefore, let us come together for the children and do whatever we can, wherever we can. To participate in Priya’s research, contact her on priya.tiss.2018@gmail.com

White House Press Release Falsely links Gender Violence (and FGC) to Foreign Nationals

By Geethika Kodukula (Disclaimer: Although they graciously accepted it, the views in this post are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of Sahiyo or its founders. I am not myself an immigrant, Muslim, or an FGC survivor.) In January, the White House put out a press release wherein they mentioned a Department of Justice report about the Entry of Foreign-Born Terrorists into the United States and the “connection” to Gender-Based Violence. The press release noted more than 20 “statistics” and names of people who have either been convicted of terrorist activities or conspiring against the US between 2001 and 2016. All of the cited examples were of people keeping Islamic faith, children of visa lottery recipients, or children of foreign-born nationals. Nowhere in this press release is there mention of the multitude of hate-crimes against people of color in 2017 or the half a dozen shootings in the month of January that are more pressing and real concerns for national security. As a statistician, I can tell you with certainty that numbers do not mean anything if you do not have a baseline to compare against. For example: let’s examine statistics about crime from the FBI. In 2016, there were 6,121 hate crimes in the United States. However, before believing that we must leave the country because it is unsafe, it is important to note that only 11.6% of the total number of jurisdictions monitoring hate crimes reported any incident. In other words, 88.4% of jurisdictions had no incident report of a hate crime whatsoever. Cherry picking numbers and placing them onto an entire group does not make the statistical interpretation valid. According to the White House Press Release, two ‘threats’ immigrants bring into America are gender-violence and crime. Let me rephrase that – the current administration, led by this man, who hired people like Rob Porter and David Sorensen who touted their professional prowesses in response to them giving their wives black-eyes, is worried about immigrants bringing gender violence into the country. Gender Violence is pervasive across the world. “Global estimates by the World Health Organization indicate that about 1 in 3 women worldwide has experienced violence in their lifetime.” [WHO | Violence against women] Factually, there is no continent on which there hasn’t been some form of sexual harassment or assault, including Antarctica. If you want some stats on the issue, go to UNWomen. I could (and desperately want to) pick apart each of the statistics provided in the White House statement intended to make us clutch our pearls and shriek at the sight of a ‘foreign-national’. However, I will resist the urge and stick to the point that made me decide to write this piece. From the White House statement: “According to a 2016 report by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of women and girls at risk of undergoing female genital mutilation (FGM) was three times higher in 2012 compared to 1990. The CDC report states that the increase was entirely a result of the rapid growth in the number of immigrants from FGM practicing countries.” One concern/question that immediately comes to mind: what was their methodology to predict that increase? Let’s check the report: “For comparability of terminology with earlier analyses, those at risk consisted of the number who potentially underwent or would potentially undergo FGM/C in the future if the population of foreign-born women and girls and their children in the United States had the same rates of FGM/C as the countries in which the girls or their mothers had been born.” To put it in perspective, the statement assumes that if a country has, say, 20% prevalence of FGC, and we have 100 immigrants from that country, 20 of those immigrants are at risk for FGC/M. The inference is then that after people emigrate to the United States, they behave in the same manner as they would in the country from which they migrated. The study does not take into account assimilation of immigrants, a difference in socioeconomic status, nor that FGM/C is banned in the United States. The CDC study itself notes that ‘These differences would very likely result in reduced risk for FGM/C’. Whoever wrote this press statement did not read the entire CDC study, or they just choose to conveniently leave out that point. Alternatively, they must have thought that no one would read the actual CDC study in its entirety and instead the public would align with the narrative that we must all run from the scary foreign-man? FGC is a real public health problem prevalent around the world, including in the United States. We are all trying to understand, reason, and reduce its incidence. We would be rejoicing if as a shift from the norm, the statement had said, ‘We can not tolerate this practice anywhere; here on U.S. soil, or across the world. We will work towards grassroots education, de-stigmatizing, and progress in the elimination of FGC.’ The White House Press Release leaves me to wonder, is the U.S. still a champion of human rights across the world, or, are they okay as long as any violation that occurs is just not in their backyard? FGC has its origins rooted in the patriarchy and suppression of female sexuality. Expecting the Trump administration to understand the nuanced situation of harmful religious practices is almost pointless. It is a war and not a battle. However, I will be damned if I stand by and watch these false “champions of women’s safety and health” demonize people without caring about the implications of their statements. At this point, if a ‘foreign national’ pulls his ear three times before eating his lunch, it seems the White House will find a reason to make it an issue relating to economic/health/crime/gender-violence. The gender-violence statistics in the United States are staggering. For many of us, it is our day job to end it – day-in and day-out. Gender-violence, like many forms of violence, is about power. Don’t let

My fight with a male cousin who thinks Khatna is good

By: Shabana Feroze Every year, Feb 6 is International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation by the United Nations. Being a survivor of FGC myself, I’m an active volunteer with Sahiyo, and as such, I shared a post about the day and about Sahiyo on my Facebook profile page. I got a few likes but after a few hours, one of my male cousins commented on the post with a link to femalecircumcision.org. The article on that website spoke about how FGC is necessary and a good thing. When I saw that comment, I was naturally affronted. The first thought that ran through my head towards my male cousin was – no vagina, no opinion, sweetheart. It bothers me so much that MEN think they can make decisions on what needs to be done to women’s bodies. You are not a woman. You are not entitled to tell women what we can or cannot do with our bodies. I underwent FGC when I was seven. I’m the one who was traumatized. Not you. I’m the one who has to deal with the pain that part of my body is missing because of a traditional ritual, not you. How dare you tell me that what happened to me was necessary and a good thing and that it should continue happening. I had a long argument with him through Facebook comments, telling him the thoughts I listed above. I even said that if he thinks the practice is good and necessary, then the girl should be able to grow up and decide to do it for herself. His response, “My Body, My Rights is a cheesy line”. His lack of acknowledging my personal experience in having undergone FGC said to me that he believed the larger society could do anything to my body or to any one else’s body. He then posted another link from the same website on consent and parental rights. The article claims “Although regulated, a parent’s right to make decisions on behalf of a child is acknowledged as fundamental and universal, even for practices which can cause harm to the child and carry no medical benefit.” Yes, the article acknowledged that FGC is harmful, but the article lessened the pain, and compared FGC to practices such as ear piercing and vaccinations. These procedures are legal and harmless. The article also claimed that Prophet Muhammad said FGC should be done, and gave a few spiritual and religious reasons like ‘taharah’ for doing so. His recurring point was that KHAFZ IS NOT FGM (written in caps). Throughout the conversation of me refuting his points with science and hard fact and telling him that the World Health Organisation recognizes all forms of cutting of the female genitalia as FGM, I found that his counter points were always mired in spirituality and religion (this cousin of mine is a mulla or a sheik in the Bohra community). I find the entire notion that ‘khafz is not FGC’ as preposterous. It’s the same thing, no matter what name you give it. Medical research has shown that FGC is harmful. FGC is opposed by the United Nations and the World Health Organization. So please don’t tell me that FGC is a good thing. Further what really, truly angers me is that my cousin, this MAN is fighting me on and issue that affects the woman’s body, my body! My cousin’s attitude reminded me of his male privilege, and his inability to understand that he has no ability to control my body or to think he knows what is best for me as a woman. And this reality scares and saddens me the most because my cousin is also the father of two girls, who if they undergo FGC, will forever be reminded that they too, just like me, had no control over our own bodies.