New Report from the Population Institute on GBV: “Behind Closed Doors: Exposing and Addressing Harmful Gender-Based Practices in the United States”

Read more in “Behind Closed Doors: Exposing and Addressing Harmful Practices in the United States.” Sahiyo is proud to help announce the publication of a new report by the Population Institute a nonprofit that advocates for gender equality and universal access to sexual and reproductive health services, titled, “Behind Closed Doors: Exposing and Addressing Harmful Gender-Based Practices in the United States”. The report tackles various forms of gender-based violence (GBV) occurring in the United States including female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C); child, early, and forced marriage/union (CEFMU); femicide, andvirginity testing. The report seeks to emphasize how prevalent these practices are in the United States, as they are often dismissed as harms that occur in foreign countries or other cultures, not here in the United States. However, these forms of GBV are increasing in the U.S. As reported by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, with more than 500,000 women and girls are estimated to have undergone or are at risk of undergoing FGM/C in the US. The Tahirih Justice Center reports that at least 300,000 minors are estimated to have been married in the United States between 2000 and 2018. While theViolence Policy Center states that the rate of gender-based murder in the U.S. continues to be the highest amongst high-income countries, with a reported 2.2 per 100,000 women being intentionally killed in 2021. Women in the U.S. are 28 times more likely to be murdered with a gun than women in peer countries. These statistics highlight the need for educating people in the U.S. about the prevalence of various forms of GBV. This report also hopes to bring this crisis to the attention of U.S. policymakers, and other government officials who cansupport advocating for culturally competent legislation, survivor-focused initiatives and programs, and comprehensive sexuality education to counter these harms. Gender-based violence affects us all. Let’s create a culture of support and solidarity to uplift and empower survivors. Read about the widespread nature of harmful gender-based practices in the United States in the Population Institute’s latest report, “Behind Closed Doors: Exposing and Addressing Harmful Gender-Based Practices in the United States”.

UNICEF releases new data on global prevalence of FGM/C

By Rachel Wine On March 8th, 2024, UNICEF released Female Genital Mutilation: A Global Concern, a new report with updated data on the global prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). Compared to data released eight years ago, this reveals a 15% increase in the practice; survivors now number at 230 million. Data in the report also indicates slow progress to ending FGM/C, with a lag behind the population overall, and stagnation in some countries. One such country, The Gambia, recently voted to repeal its ban on FGM/C. The report asserts that, “though the pace of progress is picking up, the rate of decline would need to be 27 times faster to meet the target of eliminating female genital mutilation by 2030.” While this report advances our understanding of FGM/C as a global practice and provides more relevant data for our work to end FGM/C, it is worth noting that Asian countries like India and Indonesia, and Middle Eastern countries like Pakistan and Iran are missing entirely. With the absence of this crucial data, we have no way of knowing the full scope of this harmful practice. This can be attributed to a lack of governmental support, as well as inadequate funding. Sahiyo recently participated in an event that draws attention to the lack of adequate funding in the FGM/C sphere, of which the real obstacles in our effects to enact change can be seen in this report. “From Rhetoric to Reality: Closing the Funding Gap to End FGM/C”, a parallel event at the 68th U.N. Commission on the Status of Women meetings, was hosted by The Global Platform for Action to End FGM/C in partnership with the United States Mission to the United Nations on March 15th. The Global Platform For Action to End FGM/C led the charge at the 2023 Women Deliver Conference to acknowledge the harms of insufficient funds in the work to end FGM/C. According to a Joint Letter by the Global Platform: “By investing $2.4 billion by 2030 we could end FGM/C altogether in 31 priority countries. There is also a need to expand funding beyond the 31 countries which have national prevalence data on the practice; and provide funding for anti-FGM work in countries which have not traditionally been prioritized, including in Asia and the Middle East. Yet only $275 million in development assistance is available leaving a funding gap of >$2.1 billion; and these funds are not available proportionately across all countries where FGM/C is known to take place.” This statement certainly manifests in the data of the UNICEF report. In collaboration with hundreds of activists, grassroots organizations, international NGOs and academics who gathered at the Women Deliver 2023 Conference in Kigali, Rwanda, the Global Platform has created the Kigali Declaration to call for an increase and shift of funding to grassroots organizations, and a convening of a Global Summit for increased commitments and investments. You can sign onto the Declaration here, and join the growing number calling to #closethefundinggap.

PRESS RELEASE: Sahiyo publishes Examining the Current State of Critical Intersections: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting and Social Oppressions report

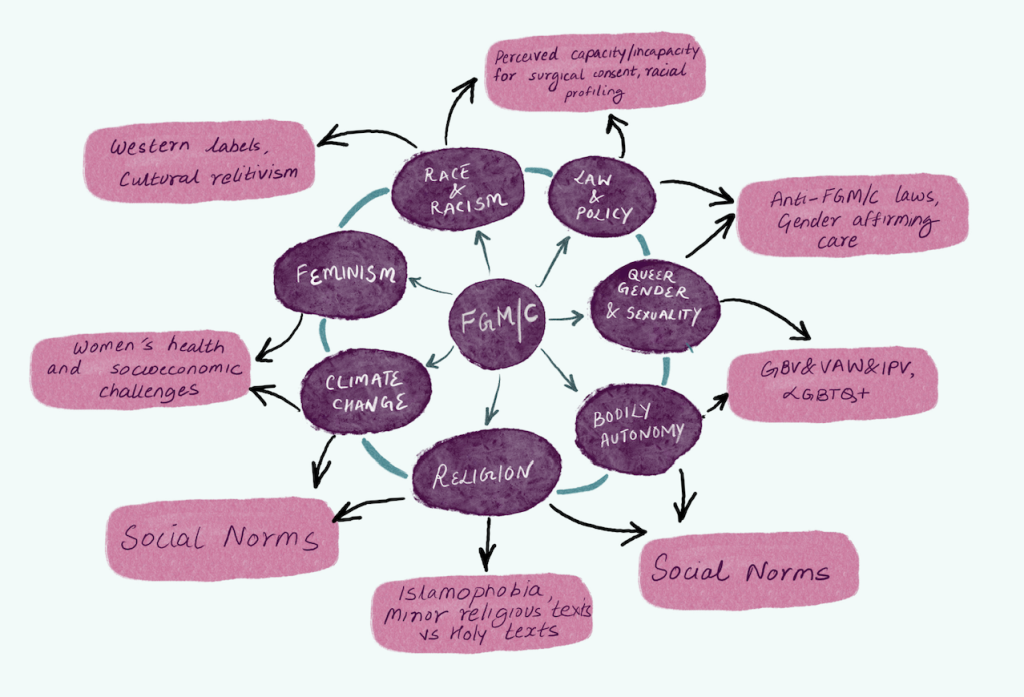

Sahiyo U.S. is proud to announce the publication of our new report, Examining the Current State of Critical Intersections: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting and Social Oppressions. The report explores how different forms of oppression intersect to affect survivors’ access to resources, as well as how the work to end FGM/C is connected to other social justice movements. The inspiration for the report sprung from a webinar that Sahiyo U.S. hosted in July of 2021 titled, “Critical Intersections: Anti-Racism and Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C).” This discussion highlighted how systemic racism negatively affects the work to end FGM/C. The webinar was highly successful, engaging more than 300 people. Using that momentum, with funding from Wallace Global Fund, Sahiyo U.S. launched a research project to further understand how different forms of oppression affect marginalized communities that practice FGM/C, and how to connect with other social justice movements to strengthen efforts in ending FGM/C. The report breaks down how the following themes, and how they intersect with the harmful practice of FGM/C: Religion: FGM/C occurs within many different religious communities, yet a focus on Islamic communities falsely correlates the practice with this religion, negatively impacting women and survivors of FGM/C with an Islamic background and furtherheightening Islamaphobia. Race: common assumptions about FGM/C are often based on racist stereotypes. Type III FGM/C (infibulation) is often called “African FGM/C,” while less severe types of FGM/C such as Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type II (excision) are associated with Asian countries. This racialized distinction can be used to justify the practice by some FGM/C practicing communities Bodily Autonomy: there is great potential for collaboration between anti-FGM/C work and the #MeToo movement. Violations of survivors’ bodies at an age where they do not fully understand how their body functions inhibits their ability to assert bodily autonomy; similarly, survivors of the #MeToo movement lost autonomy over their bodies through experiences of sexual violation. Queer Gender and Sexuality: the practice of FGM/C itself forces survivors to comform to cisgender and heteronormative ideas of what a woman is. LGBTQ+ survivors are underrepresented in statistics and the FGM/C activist community, and face an intersection of barriers that causes erasure from the FGM/C sphere. Feminism: there are many complexities at the intersection of FGM/C and feminism. Both the resister and accommodator of FGM/C may argue that their actions are aligned with Feminist philosophy based on their reasoning. Law and Policy: In the U.S., state laws on FGM/C have been co-opted to ban gender-affirming healthcare for minors. Globally speaking, law and policy has led to the criminalization of FGM/C, creating opportunities for ending of the practice, or giving practitioners reason to continue it in secrecy. Climate Change: marginalized groups are more adversely affected by the climate crisis because they do not have economic resources to protect themselves. This puts financial strain on these communities, and makes women and girls more susceptible to oppression and violence, including FGM/C. It is our hope that this report will support advocates working in FGM/C to better understand how these intersecting oppressions affect the work to end FGM/C and survivors, and connect fellow activists and social change makers to unite in ending universally oppressive systems. Read the full report here. Learn more about the Critical Intersections Research Project.

Sahiyo to launch first report from Examining Intersections Between FGM/C and other Social Oppressions Research Project

Sahiyo is excited to announce the upcoming publication of our new report, Examining the Current State of Critical Intersections: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting and Social oppressions. The report explores how different forms of oppression intersect to limit survivors’ access to resources, as well as how the work to end FGM/C is connected to other themes across the human experience. In July 2021, Sahiyo hosted a public webinar titled, “Critical Intersections: Anti-Racism and Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C).” The discussion highlighted how systemic racism negatively effects the fight against FGM/C. The webinar was highly successful, engaging more than 300 people. Using that momentum, Sahiyo launched a research project to further understand how different forms of oppression affect marginalized communities that practice FGM/C and how to connect with other activist movements to strengthen our efforts to end FGM/C. This report is the first of a series on this research, and identifies current understandings of critical factors intersecting with FGM/C and outline the gaps in our knowledge. The publication is organized around seven core themes that intersect with FGM/C: religion, climate change, feminism, race and racism, law and policy, queer gender and sexuality, and bodily autonomy. This review serves as a significant starting point for Sahiyo’s own data collection for the Examining Intersections Between FGM/C and other Social Oppressions Research Project, the results of which will be disseminated in Feb 2024.

The impact of Bhaiyo: How male allies work to end female genital cutting

Today, on International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, Sahiyo is proud to release our program impact report, Bhaiyo: A Male Ally Initiative to Support Ending Female Genital Cutting. The report spans the duration of our Bhaiyo program, from its creation in February 2021 through December 2022, and covers our challenges, lessons learned, and future paths for growth. Bhaiyo, meaning ‘male friends’ or ‘brothers’ in Bohra Gujarati, was launched to create a space where male allies can collaborate, spark dialogue, and spread information about the harms of female genital cutting (FGC). In particular, Bhaiyo participants work by engaging communities at the grassroots level to address and build awareness of the harmful nature of this practice and its consequences on their loved ones and the community in general. Since the program’s launch: 15 men joined the Bhaiyo program 13,247 people engaged with our public awareness campaigns 36 people participated in our public awareness campaigns 176 people attended Bhaiyo male-engagement webinars 28 blog posts written to uplift the voices of male activists 81.3% of members have joined additional programming efforts after joining Bhaiyo February 6th is a day for activists, advocates, and stakeholders to come together, raise awareness, and advocate for the end of FGC. Today, and for the rest of the month of February, we’re uplifting the work of Bhaiyo because we’re proud of the program’s accomplishments. We hope you’ll take the time to learn more about how we’ve been engaging men in the work to support survivors and prevent FGC for future generations. “Bhaiyo allows men to have open and honest conversations about a topic they may or may not know but should be important to them. As brothers, it’s our collective responsibility to leave the world safer than we found it for those that we love. Bhaiyo aims to raise awareness to help advocates and survivors working to end FGC today.” ~ Murtaza Kapasi We also have an upcoming Bhaiyo event that is open to the public! Date: Thursday, February 23rd Time: 9:00 am EST (New York) / 7:30 pm IST (India) Who: Current Bhaiyo members & Prospective Bhaiyo members (anyone interested in supporting male engagement on the topic of ending FGC) Register: bit.ly/BhaiyoCommMeeting To join our Bhaiyo program, please fill out this application form.

UNFPA launches 2020 State of the World Population Report

By Hunter Kessous On July 30th, the United Nations Fund for Populations Activities (UNFPA) hosted a virtual event to launch the 2020 State of the World Population Report. UNFPA is the sexual and reproductive health agency of the United Nations. This year’s report titled, Against My Will, focused on three of nineteen harmful practices girls and women face: child marriage, female genital cutting (FGC), and son preference. Son preference is a symptom of gender inequality that results in harmful practices such as gender-biased sex selection and neglect of female children. Speakers included Chrissy Houlahan, U.S. Representative; Sarah Craven, UNFPA; Sarah Hillware, Women in Global Health; Dr. Kakenya Ntaiya, Kakenya’s Dream; Jeanne Smoot, Tahirih Justice Center; and moderator Seema Jalan; UN. First to speak was U.S. Representative Houlahan who introduced the Support UNFPA Funding Act, a bill of which she is the lead author. Currently, the U.S. is withholding funding from the UNFPA for the fourth consecutive year. Houlahan calls on organizations to endorse her bill and on fellow Congress members to co-sponsor the bill in order to provide funding to the UNFPA. Following Houlahan’s important message, Sarah Craven introduced the Against My Will report. Craven summarized the report as demanding respect for the autonomy of women and girls; demanding protection of women and girls by enacting laws and changing societal norms; and stating governments must fulfill their obligations under human rights treaties. Panelists Hillware, Ntaiya, and Smoot spoke on the importance of this report in the era of COVID-19. The attention of the media and policymakers is elsewhere as we grapple with the pandemic and the growing issues of police brutality. However, the virus has also increased the marginalization and vulnerability of girls and women. Reports such as this refocus attention on gender-based violence and empower us with tools to continue fighting these harmful practices. In response to the growing conversation about institutional racism, the panelists remarked on their organizations’ action steps. Smoot highlighted the importance of fighting all forms of oppression in order to abolish gender-based violence. Hillware calls on activists to work both internally and externally, meaning organizations should work toward intersectionality within their own staff. Ntaiya was asked how she walks the line of abandoning FGC in Kenya while still showing respect for the parents of the girls with whom she works. Ntaiya made an important point that FGC elimination requires all people within the community to be on board. Teaching the harms of FGC to girls in school won’t be effective if they are going home to a community that preaches an opposite viewpoint. For this reason, she works to educate parents, chiefs, health system workers, elders, and more. Ntaiya notes the need for a more holistic system for ending FGC. She provided the example that the chief may want to enforce anti-FGC laws, but lack the resources to do so such as a car to rescue girls, a hospital to take them to, etc. In addition to education for the community, we must implement other systems to make ending FGC possible.

A tale of deception: My conversation with an FGC survivor in Pakistan

By Hina Javed (This is the third part in a series of essays by Hina Javed on her experience of reporting on FGC in Pakistan. Read the whole series here: Pakistan Journal.) The time had come to pick up that phone. Little did I know that my conversation with an FGC survivor would be more harrowing for me than the talk which revealed its existence to me in Pakistan. I picked up the phone and made contact with my second survivor, 37-year-old Sophia. The woman narrated the time when she, just a girl of seven, was led into a dimly-lit room, full of strange odors and even stranger people. This was not the shopping trip the minor had in mind when she was told earlier in the day that her aunt was taking her out. As if the surroundings were not distressing enough, the girl was forced to lie down on the floor and soon a complete stranger was reaching between her legs. The moment she was ‘cut’, she let out a loud scream and tears started rolling down her face. When it was over and done with, the matter was hushed up and never spoken of again. Three decades on, a now grown woman remembers vividly the day her freedom of choice was taken away: I still remember it distinctly. I feel slighted, even to this day, at how they held me down despite my attempts to push them [the strangers] away. But most of all, I feel angry at how they buried the matter under blankets of silence and pretended like it never happened. The day I walked out of the dingy apartment, I thought I was punished for being ‘bad’. I was mortified to look even look at the cut. I wanted to lie down in my mother’s lap and forget everything; to assume, for a split second, that what existed between my legs wasn’t shameful. When I grew up, I was finally able to connect the dots. The ‘cut’ was a symbol of my sexual submissiveness. Just like vaccinated animals, I was now wearing an imaginary ear tag signifying the death of the ‘parasite’ [or bug] driving my sexuality. From then on, I was to be categorised as a woman of ‘decent’ character. The truth is, I was just another offering to a centuries old tradition. The decisions made about my body came from a group of elderly women who believed it was a necessary rite of passage. And the cherry on top was that I was made to kiss my hostess’s hands as a gesture of respect. I didn’t speak about the incident for the longest time. I feared it would be considered rude and impolite. But there came a point when it became difficult to contain my angst and disappointment and I ended up asking my mother. I now realize that it wasn’t her fault either. I wonder if my anger towards my mother was even justified. Without a shadow of doubt, she was under immense pressure from family elders. If she tried to get away with it, they would have found out and ostracised her from the community. I am now a happily married woman with two beautiful children, but I feel a sense of deep remorse when I engage in sexual activity. I feel immoral, sinful and unclean. The trauma is so deep that the act itself becomes an unpleasant experience. It is difficult to be psychologically scarred and feel completely at ease. Sadly enough, our generation still believes sex is a dirty, reproductive act. We are trained to associate sexuality with immorality. We grow up with warnings that if we express our desires, we are deviant and dirty. We have spent our entire lives in the absence of this conversation, but we need to have it anyway. This avoidance has robbed several women of their identities. I have tried to bring this up many times with little progress. I am already estranged from my family over disagreements. What is surprising is that these decisions are made by women. The misogyny is so deeply internalized that they are unable to look squarely at the sexist world around them. Upon hearing Sophia’s story, I recognized the extent of psychological and physical damage the ‘cut’ had on her. She was in perpetual dilemma: on the one hand she wanted to speak up about her experience, but was also overcome with guilt and fear. It was evident that she was unable to shake off the impact of the incident to this day. As she finished speaking, there was a momentary pause as I struggled to thank her for speaking up about her experience. “I wish I could allow you to quote my name. There is a dire need to elevate this conversation in every country, especially Pakistan. However, there is immense pressure from my community due to which I want to remain anonymous,” she said. “I understand,” I replied. “I hope your story stirs a conversation and becomes a movement in this country. We need to put an end to this contested practice.” (*Sophia is a pseudonym. The person’s original name has been changed to protect her identity.) (Hina Javed is an investigative journalist based in Pakistan, driven by the ambition of tackling difficult, often untouched topics. Her focus is on stories related to human rights, health and gender.)

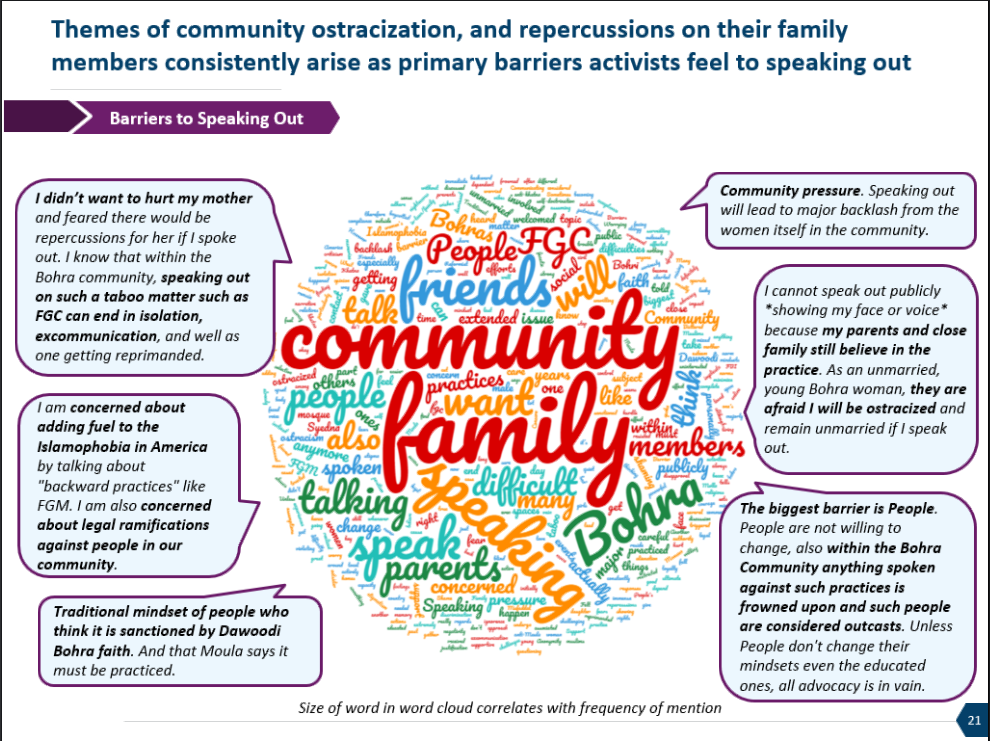

Sahiyo Activist Needs Assessment: Learning How To Support FGC Activists

Research Summary & Implications Background Sahiyo is dedicated to ending Female Genital Cutting (FGC) in the Bohra community, a small global Shia Muslim community. Sahiyo focuses its efforts on public education about the prevalence and impact of FGC, community outreach initiatives, and supporting survivors and activists, with the ultimate goal of driving positive social change around gender violence. Sahiyo recently partnered with a healthcare market research consultancy to conduct primary market research with activists speaking out against FGC, in an effort to better understand activists’ challenges and hopes for the future. In this article, we hope not only to summarize the key findings from our primary research and draw implications for the broader gender violence activist community, but also to underscore the importance of conducting primary research with activists. Research Methodology Research entailed two phases: first, a quantitative, online survey was sent to anti-FGC activists across the globe. Second, follow-up interviews were conducted with activists from the online survey sample, who expressed their willingness to further participate in the research. Sample & Demographics All activists who took part in this research grew up in the Dawoodi Bohra religious tradition, and are now self-described as active in speaking out against FGC (‘khatna’). Phase 1 Quantitative Sample: Between 40-50* activists took the online survey, 91% of whom were female. Activists’ ages varied, though 56% were under the age of 35. The majority (~3/4) of activists reside in either the United States or India and were highly educated, with 96% having at least some graduate degree. Although respondents were raised Dawoodi Bohra, only 43% still identify as Dawoodi Bohra, while 37% are non-practicing. However, 67% of respondents socialize with Dawoodi Bohras at least sometimes (every couple of weeks). 69% of respondents personally underwent FGC, while 94% had a mother who was cut. Phase 2 Qualitative Sample: 7 activists were interviewed in follow-up telephone conversations. These 7 activists had variable ages, countries of residence, and genders. Key Findings Although each activist’s story is unique, they all shared the drive to end FGC in their community and more broadly. Their activist journey typically started with a realization about the prevalence of the practice: whether this be through a family member speaking out, a documentary, or media coverage; the realization sparked further investigation. Although some activists had memories of their own experience of being cut, many did not. For the latter individuals, the realization as adults about the practice’s prevalence occasionally came with a realization that they too had been cut, triggering an intense emotional response. For all activists, the initial anger and shame upon learning of the practice’s prevalence often led them to ask family and friends about FGC in their community, but they were met with a culture of secrecy and silence. Even when activists did open conversations with family and friends, they found the practice was often justified as a longstanding tradition, necessitated by religion. This culture of secrecy and acceptance, paired with painful body or narrative memories of their own cutting, were said to be key drivers to speaking out. Many activists feel that not only does FGC have long-term physical and psychological health impacts, but that it is also a form of child sexual assault and/or abuse given the lack of consent. Furthermore, activists acknowledge that FGC’s underlying misogynistic and patriarchal factors make it part of a larger movement to control women. In short, activists feel that FGC does only harm with no benefit and must therefore be ended. Challenges to speaking out: Overlap of religion and community The most significant challenges activists face when speaking out stems from the high degree of overlap between religion and community in the Bohra community. Although most activists are fairly open with their families and friends about their activism, they feel only moderately supported by their loved ones, largely due to concerns with the activism’s social repercussions. These concerns are linked to the social characteristics of the Bohra community, which include long-standing traditions of loyalty and closeness, in which the religious community often dictates social circles, romantic partners, neighborhood housing, cemetery sites, and more. This overlap causes speaking out against FGC to be seen as an attack on the community and faith at large. As a result, activists fear that speaking out would lead to discontinued social and professional bonds and ceasing of access to religious privileges. For some, these potential social repercussions bar them from speaking out publicly, so they pursue more private means of activism, such as anonymous writing and supporting organizations like Sahiyo. Religious authority Concerns with speaking out are further driven by the authority of the Bohra religious leaders. Considering that there is no clear religious justification for FGC, its continuation relies upon the leaders’ mandates and interpretations. Questioning of the religious leaders is deeply discouraged and potentially dangerous—causing many activists to not only fear speaking out, but also sometimes demotivating them, making them feel that without the support of religious leaders, their activism is a ‘lost cause.’ Considering the challenges above, many activists feel torn between wanting to end the practice and wanting to maintain a close connection to their faith and/or community. Even activists who are no longer involved in the Bohra community still fear risking the social wellbeing of their loved ones. Activists present this as a ‘catch-22’: loyal Bohra members are well respected by their community; however, speaking out against a taboo practice might oust them from it, rendering their authority no longer valid. Conversation challenges When activists do speak out publicly or privately, they find the conversation about FGC particularly challenging. The lack of robust, publicly available information about the practice’s prevalence in the Bohra community, as well as about its physical and mental consequences on the girls’ health often result in other Bohra members undermining the impact of khatna. Many community members present khatna as ‘not as bad as other types of FGC’. These arguments are particularly difficult for activists who do not have a clear memory of their own experience

What can Bohras learn from a new report on the global status of female genital cutting?

by Aarefa Johari This August, the Population Council and UK Aid published a unique, comprehensive report on Female Genital Cutting around the world, to serve as a valuable resource for anyone working to bring the practice to an end. Titled ‘A State-of-the-Art Synthesis on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting – What do we know now’, the report provides a zoomed-out analysis of all the recent available data on FGC from the 29 countries that have done national surveys on the subject. Although India does not feature in this list, the report offers plenty of food for thought for those of us in South Asia in general and the Dawoodi Bohra community in particular. In hospitals or in homes? The 29 countries studied in the Population Council report are all from Africa, except for Yemen and Iraq. But the report also acknowledges the prevalence of the practice in other countries like India, Pakistan, Oman, Malaysia, Iran and Colombia, where no national surveys have been done yet. Indonesia, where the widespread prevalence of FGC has only recently been given official recognition, has been featured prominently in the report. Types I and II are the most common forms of FGC around the world, and in the 29 countries studied in the report, it was found that the cutting is still overwhelmingly performed by traditional cutters. In the Bohra context, we do not know if that still holds true. We know for sure that in India, in big cities like Mumbai, nearly all Bohras who still choose to get their daughters cut end up going to Bohra-run hospitals or clinics. Based on anecdotal information, we also know that Bohras in smaller towns are increasingly choosing to have it done by a local doctor. For instance, one woman from a Bohra housing colony in Jamnagar told a Sahiyo founder that khatna for girls is now performed in clinics because with the traditional untrained cutters, there had been many instances of “cases going wrong”. This is disturbing for two reasons: One, khatna is now increasingly getting medicalised among Bohras, creating the entirely false impression that it is a medically sanctioned and beneficial practice. In truth, khatna has no proven health benefits at all. And two, we cannot help but think of the girls behind the many “cases that went wrong”. The word “case” is a medicalised euphemism for an actual girl, now probably a grown woman, who must have been cut more than intended, who might still be experiencing physical, psychological and/or sexual trauma that has probably never been addressed, because we are taught to be silent about these matters and because our country does not have adequate mental health resources to help those in need. How many such “cases gone wrong” have we had in the Bohra community? No one knows, because for centuries, the voices of those girls and women have been silenced. Supporters of khatna often claim that only a “small number” of Bohra women have suffered negative consequences. But if just one town in Gujarat has seen “many” cases that went wrong, perhaps it is time to drop our defenses, create a positive space for all women to share their stories, and truly listen to their voices. Why is khatna practiced anyway? The Population Council report also makes an interesting point about the reasons different communities give for practicing FGC. Across cultures, there are a variety of reasons given, which can be broadly classified into certain basic themes: marriageability, chastity, social status, religious identity, transitioning into womanhood, maintenance of family honour, beauty and hygiene. But unlike popular belief, the reasons given by a particular culture or community do not remain static – “as with other social norms or practices, they are dynamic and subject to change and influence over time”. This rings true for Dawoodi Bohras around the world, where the reasons given for practicing khatna can change from one family to another. Two of the most commonly cited reasons are “it is in the religion” and “it moderates sexual urges and prevents promiscuity”. “Cleanliness and hygiene” is cited far less frequently, even though it is the “official” reason as per the Bohra religious text Daim al-Islam. This is most likely because khatna is carried out secretly, Bohra religious leaders have never publicly discussed or advocated for the practice and women have typically passed down the reasons for it as an oral tradition within their families. And some Bohras are now rationalising khatna in ways that their grandmothers probably did not – some compare it to male circumcision and claim that it prevents urinary infections and/or sexually transmitted diseases; others have started equating it with the medical procedure of clitoral unhooding and claim that the removal of the hood enhances sexual pleasure. This just goes to show that it really doesn’t matter what religious texts like Daim al-Islam or the Sahifo may say about khatna for girls. Most community members don’t seem to even be aware of what these texts say, and they have been cutting their girls for entirely different reasons. One of my own aunts once told me that girls who are not cut will turn into prostitutes – a preposterous idea that she not only believes in, but also attributes to the Prophet! The sad truth is, her daughter was cut for this reason – to prevent her from becoming a prostitute – and not for any “official” reason. Similarly, other girls are being cut to keep them chaste, and I was cut for no reason at all, because my mother just didn’t think of questioning the practice. Hope for the future The Population Council report also points out that FGC often continues within a community because the individual preferences of girls or even their mothers are “often superseded by those of elder women in the family”. Among Bohras, we keep hearing from scores of women who have experienced the same dilemma: they didn’t want to have their seven-year-old daughters cut, but eventually had to cave in to pressure from their own mothers or mothers-in-law. Many Bohra women are currently facing the same problem and are

New U.S. CDC Study Still Under Reports FGC in this Country

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released an updated report on the estimate of women and girls at risk or those who have undergone FGC living in the United States. To read the report, click here. Since the last official estimate in 1990 of how many people were affected by FGC, the number has grown to 513,00 – this number is triple the estimate from the 1990 figure. This increased figure is attributed to the rapid growth in the number of immigrants from FGC practicing countries living in the United States. Yet, these numbers are still an under-representation of the real number of women and girls who have undergone or at risk of undergoing FGC living in the United States. The report estimated this figure by applying country-specific prevalence of FGC to the estimated number of women and girls living in the United States who were born in that country or who lived with a parent born in that country. These countries included: Egypt, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, West Africa, Yemen. However, at the global level recognition that FGC occurs in countries outside of the African continent has only recently become public knowledge. In the last few years, reports of FGC being practiced in India, Pakistan, Iraq, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, various place in Africa, as well as other developed countries where immigrant communities reside (United Kingdom and Australia for example) were not included in these estimates. This limitation to the study is mentioned in the CDC’s report. Regardless of this oversight in the estimate, the increased figure does validate the need for the U.S. government to provide more education and outreach to practicing communities living in the United States. The figure also points to the need to train social workers, medical professionals, lawyers, etc on the cultural complexities of FGC along with how to work with those women who have undergone this practice in a culturally sensitive manner.