Reflections on research: Digital Storytelling as a narrative intervention for survivors of FGM/C

Being a researcher: Finding balance

By Huda Syyed The biggest challenge of being a researcher is to be impartial during the data collection process. However, for the researcher, conducting any area of research will come with some personal sentiment or perception regarding that topic. Oftentimes the researcher has to sit and contemplate how they will approach the subject despite their personal bias or opinions. I felt a surge of overwhelming feelings and thoughts when I embarked on learning more about female genital cutting (FGC) in Pakistan. A few questions that ran through my mind were: Is it ok for me to pursue this research as an outsider to the community who has not experienced FGC? I wondered if it was an intrusive decision to choose FGC as my research topic because I am not part of the community that practices it. My uncertainity and discomfort felt heavy, but also important to address before I started the data collection process. Reading and learning about FGC from books, journals, and audio-visual sources seemed like the easy part. However, when I got closer to the data collection process which involved surveying and interviewing women who underwent FGC, I felt the need to reflect upon these questions, because I wanted to ensure I was not crossing any boundaries that could cause them harm. When I realized that there is a dearth of data on FGC in Pakistan, I determined that by collecting more data, I could help build a more thorough understanding of the practice and its contextual continuation. In turn, what I found could help explain the way that communities function and whether culture or religion play a role in practices like FGC. Once it was clear as to why I was pursuing this research, I felt some relief. How can I make my paritcipants feel safe and comfortable while they share their thoughts and experiences with me? With qualitative methodologies, and especially interview formats, the interviewer must be mindful of ethical guidelines. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently launched its first ethical guidance on how to conduct research on FGC, titled Ethical considerations in research on female genital mutilation, for this purpose. It is imperative that researchers stick to these guidelines to avoid any conflict or trauma for the participants. One of the main principles of the WHO’s ethical considerations is respect for persons, which states that consent and informed understanding of the research are important elements to the ethical conduct of research. It is necessary that the researcher informs the participant about the research and only continues data collection upon their willingness. Once the researcher has familiarized themselves with the ethical guidelines and questions, they must approach participants in a non-imposing and thoughtful manner. The researcher’s demeanour must reflect that the participant has absolute free will to interject or walk away from the interview; the participant must know that they have the option to discontinue the interview without the fear of any consequences. Comfort, willingness, and the well-being of a participant should be of the utmost importance to the researcher. How can I deal with panic associated with the responsibility to have zero margin of error? Every researcher aims to produce reliable and error-free research. It is great to pursue research with a spirit of wanting to do your best, however researchers should also practice compassion and kindness towards themselves. It is easy to get carried away with the aim for perfection, and I think it is better to replace that feeling with self-kindness and appreciation for whatever you may have achieved within a day. But how does one deal with the panic of these responsibilities? I think it is helpful to reach out to other researchers and discuss your concerns, fears, and anxieties. By speaking to other research students and mentors, I realized that it is quite normal to feel this fear and panic. However, managing it in a consistent and healthy way is key to producing good research and retaining one’s sanity. This is why I made it a point to spend more time with my dogs and family to relieve stress levels. I also pursued hobbies that helped take my mind off research for a while. These small changes in my lifestyle helped me approach my research in a responsible, mindful, and revived manner. Afterall, balance is everything. About Huda Syyed: Huda Syyed is currently a Research Student at Charles Darwin University. Her research topic focuses on female genital cutting and explores an understanding of the practice and its lack of visibility in Pakistan. In the past, she acquired a Master’s degree in International Relations from Queen Mary University (London) and worked in the non-profit sector on UN Women projects that dealt with gender-based violence. She has been a research assistant and writer for a few projects and was also visiting faculty at Bahria University, where she taught ‘International Organizations’ at undergraduate level. She writes news and opinion pieces on topics related to gender and society for local and digital newspapers. Learn more about Huda’s research here.

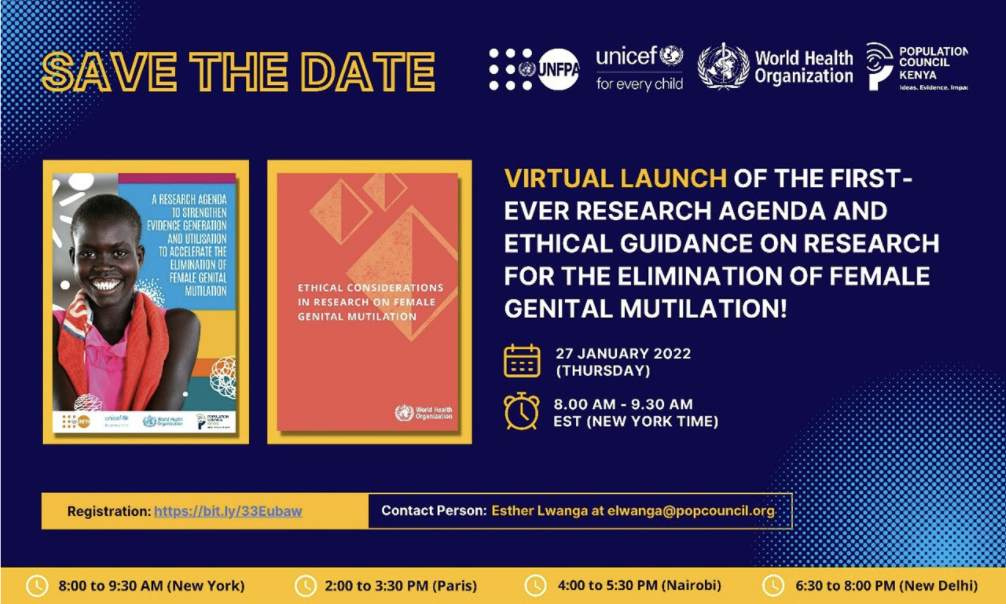

An FGC researcher’s reflection on the first-ever Research Agenda and Ethical Guidance on Research for the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation

By Hunter Kessous In my sophomore year of college, I decided to conduct research analyzing the knowledge, attitudes, and training of community health workers who work to end FGC. In the early stages of my research project, I held interviews with many wonderful leaders of organizations working to end female genital cutting (FGC). I also asked for their assistance in sharing a survey with community health workers within and outside their organization. In one interview, a leader asked me very directly “Why should we do all this work?” It was a valid question; I was requesting their incredibly valuable time and resources. Why should they take time to participate in my research specifically when there is so much important work to be done? Last week, I attended a webinar that answered her question better than I ever could have. The event was hosted by the UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO, and the Population Council, Kenya. These organizations collaborated to launch two exciting new documents: the first-ever Research Agenda To Accelerate the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation and Ethical Considersations in Research on Female Genital Mutilation. An opening statement by Nankali Maksud, UNICEF Senior Advisor, described perfectly why these documents are so needed. Every year, at least four million girls are at risk of undergoing FGC. The COVID-19 pandemic has added an additional two million cases to this figure, which otherwise would have been averted. In order to end FGC by 2030, progress needs to be 10 times faster. To achieve this goal, the work to end FGC must be based on high quality evidence, which requires 1) asking the right questions and 2) ethical guidance, both of which are addressed in these documents. To date, research on FGC prevention and elimination has been limited. The research agenda was created by performing a literature review and developing a list of questions to explore the gaps in our current knowledge. The list is very comprehensive, and the authors even ranked the questions by priority so researchers can clearly see what needs to be addressed most urgently. The document calls on researchers to ask important questions, the top priority being: “How can healthcare providers and the health system be effectively utilised in the prevention of FGM and the provision of services to women and girls affected by FGM?” The complete list of 78 research questions is broken down into thematic areas, including Enabling Legal and Policy Frameworks, FGC in Conflict and Crisis Settings, and more. The guidelines for ethical considerations when conducting research on FGC includes checklists for each step of the research process to ensure that the rights of participants are prioritized and respected at all times. The document also emphasized the importance of engaging with the community early to ensure that research will make a contribution to the health and well-being of the population. This part is essential. Research is not done simply for the sake of running numbers or getting published—research is only as useful as the extent to which it can guide policies and interventions. We must make sure research is relevant in order to end FGC. As an FGC researcher myself, I wish these comprehensive guides existed when I began my project, but this will not stop me from using them going forward. I am excited for the future of research under the guidance of these resources. It’s inspiring and hopeful to see multiple organizations come together to support the importance of evidence-based approaches to end FGC.

Reflecting on the launch of the first-ever Research Agenda and Ethical Guidance on Research for the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation

By Ellen Ince On January 27th, I attended the virtual launch of the first-ever Global Research Agenda on the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and the launch of Ethical Considerations in Research on Female Genital Mutilation. This online event, hosted by UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO, and the Population Council, Kenya. I immediately felt the buzz of excitement surrounding the launch. It is clear that the Research Agenda will be a critical resource in acting against female genital cutting/mutilation (FGM/C). As panelist Nankali Maksud put it, ‘this is just the beginning. Today is the beginning of a great day but it is not the end of this story.’ She reminded the audience that 4 million girls are at risk of FGM/C every year, and that progress needs to be 10x faster if we are to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal of ending FGM/C before 2030. The Research Agenda pinpoints refined research questions and highlights research gaps to bolster progress as we make our way towards that 2030 goal. Research outcomes will then provide evidence to policy makers, with the aim of encouraging them to take action. What struck me the most is the emphasis on community engagement and involvement of survivors as key to finding ethical solutions, which is something so central to Sahiyo’s mission as an organization. Panelist Dr. Dennis Matanda provided an overview of the research agenda and talked about the process of identifying research priorities. Of the research questions identified, I found the following two questions very thought-provoking: What intervention approaches are effective in preventing FGM across countries that border each other? FGM is not an individual or community issue. It is global. Sahiyo believes that FGM/C is a social norm with a variety of justifications for why it is carried out. To tackle FGM/C as a women’s rights issue, we must remain optimistic that social norms, while complex, can change. It must become a social norm for women’s consent to be as highly valued as men’s. Transforming attitudes concerning FGM/C in a way that is compatible with and sensitive to local culture is fundamental in achieving change. Sahiyo advocates for change whilst respecting other cultures. How can men and/or boys be effectively engaged as allies of gender equality and ending FGM? Sahiyo also includes male allies through their Bhaiyo program to take part in action to end FGM/C. Male input is crucial for gender equality to be achieved. They have an important role in promoting women’s rights and their independence. Without their support, gender equality is not possible. For those who are interested, Sahiyo is launching a new campaign, “Each One, Reach Bhaiyo” with the goal of engaging men in dialogue around female genital cutting. Please keep an eye out on our social media or email programscoordinator@sahiyo.com to learn more! You can find the other research questions here. With the Research Agenda identifying research gaps, the Ethical Guidance on Research serves as its companion. The Guidance sets out how to obtain high quality data whilst respecting key ethical principles such as respect for human dignity, autonomy, truth, justice and beneficence. Ethical Guidance is of utmost importance for sensitive topics such as FGM/C. I particularly appreciated the focus on support for the wellbeing of participants and researchers, as well as consent for individual interviews and focus group discussions. The document itself is structured around 3 stages of research: the study design, study implementation, and data analysis and dissemination. You can read the full document here. I found the panel discussion to be dynamic and informative, in which panelist Salma Abou Hussein spoke about driving change on the ground and Professor Mamadou Balde covered the ethical dilemmas that researchers are likely to face. Dr. Samuel Kimani from ACCAF (Africa Coordinating Centre for Abandonment of FGM/C) emphasised the importance for researchers to bridge the gap between evidence and action, arguing that behind the numbers there are women and girls. Their experience and feelings deserve explicit attention and should be translated into interventions and actions within their communities. This point made me reflect on the role we can all play in ending FGM/C. It was inspiring to see so many youth activists and students present on the call, taking a firm stance against FGM/C. Young people’s voices are being heard around the globe, giving them power to become drivers of change. I am sure these students found the webinar as enlightening and insightful as I did. This event, and its outputs, mark a major advancement in our work to end FGM/C.

Sahiyo’s new book club officially launches in October

Event: Sahiyo Discusses: Seven by Farzana Doctor Date: October 13th, 2021 Tme: 8 pm EST Registration Link: https://www.flipcause.com/secure/cause_pdetails/MTI0Mzc5?mc_cid=58973cee37&mc_eid=UNIQID Starting this October 2021, Sahiyo is officially launching our book club, Sahiyo Discusses, with our inaugural event, Sahiyo Discusses: Seven by Farzana Doctor. Designed to bring people together through literature, art, and media, this club will host quarterly meetings to bring together activists and allies in Sahiyo’s network to discuss the chosen piece of media. With themes ranging from feminism, equality, bodily autonomy, women-centered movements, and sexual empowerment – this club will focus on uplifting the stories and experiences of women everywhere. Our first meeting will be held on October 13th, at 8 pm EST over Zoom. We will be joined by Farzana Doctor, who will talk about her novel, Seven. Seven explores themes of family, culture, politics, and FGM/C with a surprising ending. Sahiyo Discusses members will have the opportunity to discuss the book with Farzana as well as ask pertinent questions. Admission to Sahiyo Discusses will be on a pay-what-you-can basis, with a recommended suggested $10.00 USD donation per event. If you or anyone in your network is interested in joining us please register and donate here. Thank you all for your continued dedication to Sahiyo’s mission, and we look forward to seeing you all there!

Absence of female genital cutting laws in India: An issue that requires immediate action

By Richa Bhargava Age: 20 Country: India As a first year law student in Sonipat, India, I was exposed to the practice of female genital cutting (FGC) as a part of my sociology course. We discussed the practice briefly. The article that formed a majority of our discussion only spoke of the existence of FGC in African nations and made no mention of India or other countries around the world where women are subjected to the practice. I felt shocked and truly disturbed when I first learned about FGC, and as a result, my response was to read about it on my own accord. A little browsing led me to the discovery of the fact that FGC prevails in the Indian subcontinent as well. I read about the Bohra community, the absence of legislation and the organisations and people advocating to end this harmful and unnecessary practice. Laws do not just force and punish. They deter, discourage and dissuade, too. Enacting and legislating laws raises awareness and empowers communities to change not only what people do, but what they think is right. It is vital for laws to continuously evolve with the changing norms and ideals of a society. FGC is a prevalent practice among the Bohra community in India. A study indicated that almost 75% of the women of this community who were interviewed have been cut. At present, many citizens are unaware of its presence in India. Lifting the veil off this practice is an essential step toward ensuring that a conversation regarding its harmful effects on young girls begins. Maneka Gandhi, a union minister, stated that there is a lack of proof regarding the existence of FGC in India, and there is no data to support its presence. The Ministry of Women and Child Development needs to conduct surveys and take appropriate measures to find all data that would make the legislators see the need for the enactment of a law against FGC. To avoid addressing the issue is to completely ignore its existence. A similar approach has been taken up by the Indian government over the years. Multiple accounts of women who have undergone FGC are out in the public domain and provide substantial evidence to prove the presence of khatna, as it is known in the Bohra community. Yet, no legislation or statute has been formulated or enacted in India which would help survivors find an easy legal recourse. There is an imperative need to move beyond the pretext of not having enough data to prove FGC occurs in India. Hundreds of survivors have spoken up against this practice and have openly shared their painful accounts. Many survivors have shared that since khatna is secretive, making it unlawful could have a serious impact in curtailing it. According to Section 320 and Section 322 of the Indian Penal Code, causing grievous hurt to another person is a criminal offence, and FGC would automatically fall within its purview. Despite this, there has been no effort on the part of the legislators to specifically provide remedy to survivors. The Indian Constitution guarantees the fundamental right to life and liberty to all its citizens. Legal statutes like the Indian Penal Code and the Prevention of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act that penalise crimes should mention terms such as female genital mutilation/cutting, labia minora, etc., to provide appropriate legal recourse to women affected by this practice. India claims to be a welfare state that ensures the well-being of all its citizens. Refusing to ensure the safety of young girls who might be subjected to FGC is a contradictory act. Various jurists and legislators face the problem of deciding whether one fundamental right should be given more importance than the other. The proposed ban on khatna raises a similar obstacle. The Indian Constitution confers upon its citizens the right to equality, as well as the right to practice and profess any religion. There exists a constant clash between articles 14 and 15 defining right to equality and articles 25 and 26 defining religious rights. In particular, the rights guaranteed to people under article 26 pose a unique challenge before the courts. In recent years, courts have come to realise that the right to equality should be awarded more weight. Discrimination solely on the basis of one’s gender is highly dishonourable and unjust. In order to move forward, a distinction between social malpractices and actual religious practices needs to be made. Social norms disguised as religious practices infringing upon the rights of women need to be done away with. The right and autonomy over one’s body is crucial to live a respectful life. People frequently wonder whether legislation can bring about change. Fear that criminalising FGC might result in a deeper continuation of it is felt by many and is a valid concern. However, often the notion that a new law can elevate conversation on FGC and create a discourse for all to engage in on the topic is overlooked. The existence and continuity of khatna cannot just be attributed to the fault of a community. With democratic ideals such as equality and freedom, the state cannot shy away from establishing and constituting laws that are in symmetry with these ideals.

Mutilation or enhancement: A researcher’s argument for respectful terminology on genital cutting

By Brian D. Earp I have published several papers on the ethics of medically unnecessary genital cutting practices affecting children of all sexes and genders. When my writing touches on the sub-set of these practices that affect persons with characteristically female sex-typed genitals, I have received some pushback for using the term female genital cutting (FGC) rather than female genital mutilation (FGM). An instance of such pushback came from a respected colleague in response to a paper of mine in Archives of Sexual Behavior, in which I argue against the use of ‘mutilation’ in certain contexts, as there is evidence that such stigmatizing language may have adverse effects on the very people who are meant to be helped. Given that this terminological issue is likely to keep coming up, I thought I would share parts of the reply I wrote to my colleague. I hope it can shed some light on at least one plausible way of thinking about such matters. My colleague argued that my use of ‘FGC’ rather than ‘FGM’ is disrespectful because it goes against the recommendation of the 2005 Bamako Declaration adopted by the Inter-African Committee (IAC) on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children. ——— On the matter of disrespect. I have had many conversations with women who consider themselves circumcised, rather than mutilated, and even if they agree that medically unnecessary genital cutting should not be performed on persons who are incapable of consenting, primarily children, they insist that it is harmful, stigmatizing, and paternalistic for others to simply define their own modified genitals as mutilated (a term that implies disfigurement or even an intent to cause harm). They explain that their loving parents, however misguided, did not intend to cause them net harm, just as, for example, Jewish parents who authorize that their sons be circumcised do not intend to harm them, but rather, take an action that is sincerely believed to appropriately integrate the child into an ancestral community. They recognize that, in their own communities, both male and female genital cutting practices are widely seen as improving the genitalia, including aesthetically, which is contrary to the very notion of mutilation. I may not agree with that interpretation myself, but it is not my position to tell these women (or their brothers) that their altered genitals are ugly or disfigured rather than, as they see it, aesthetically (or in some cases, culturally or religiously) improved. I will ask: Were these leaders democratically elected to express the considered opinions of their constituents, or were these leaders self-appointed? At the very least, they cannot have been authorized to speak on behalf of countless Southeast Asian or Middle Eastern women who have been affected by ritual forms of female genital cutting. In any event, I face a choice. I can disagree with the conclusion of these African leaders who seem to feel qualified to speak on behalf of millions of other women, including non-African women, and impose an entirely negative and stigmatizing interpretation of all of their altered genitalia regardless of how those women see their own bodies. Or I can show respect to those women who have shared their stories with me, as well as all the women in various reports and testimonies who have expressed strong objections to the term ‘mutilation’ being forced on them, and who would simply like to have the room to be able to evaluate and describe their own genitals as they see fit. One woman explained her feelings: “In my opinion, the word ‘mutilation’ used in reference to [what happened to me] is a degrading and disempowering term that strips women of their dignity and self-worth. Basically, it is a label that has the power to negatively influence one’s self-identity. If you understand labelling theory you will understand how damaging/influential a term or classification can be to an individual.” She continued with her experience: “Having just about survived my ordeal of forced body alteration I was very aware of the violation to my body. However, the introduction of the term ‘mutilation’ into my consciousness affected me mentally and physically. It made me view myself as an ugly, mutilated, and frowned-upon member of society. There started my journey of self-hate, which presented itself in many forms, including bulimia and social anxiety, to name but a few. To be called the ‘mutilated’ girl by health professionals stripped me of any dignity and covered me in shame on numerous occasions. Thankfully, I no longer see myself as a victim or survivor of ‘FGM’ – I refuse to allow that term to take away my power or to define who I am.” Faced with the choice between respectfully disagreeing with the analysis and conclusion of a group of leaders whose qualification to speak on behalf of others I do not know, versus showing respect to those women, such as the one quoted above, who have asked for the right to determine their own victim status (including whether they regard their genitals as mutilated or otherwise), I choose the latter. Referring to “the event” and “the torture” is using singular language to refer to a plurality of quite different events carried out in different ways by different groups for different reasons. As you know, the World Health Organization (WHO) uses the term FGM to refer to a dozen or more practices, ranging from nicking of the clitoral hood, which does not remove tissue. In many communities, for example in Malaysia, it’s often done by a doctor with sterile equipment and pain control, through to excision of the external clitoris with a rusty implement and no pain control followed by infibulation, as occurs in some rural parts of Northeast Africa, for example. It is entirely accurate to say that all of those quite different interventions are medically unnecessary acts of genital cutting; and I argue that all of them are morally impermissible if carried out on a non-consenting person. I have written about labiaplasty, a common procedure in Western countries. I

What I learned from survivors and advocates on my podcast about female genital cutting

By Aubrey Bailey I graduated this April 2021 from Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in graphic design. For my senior capstone project I was instructed to choose a topic that I would stick with for a year and then conduct in-depth research, write a research paper, and display my findings visually through an exhibition. In April 2020, I went home to Gilbert, Arizona, to finish my winter semester under quarantine because of COVID-19, and while I was home my dad introduced the topic of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). I was dumbfounded that I had never heard of it before. I could not fathom that so many women were undergoing this practice in different parts of the world and I did not know about it. If I do not know about this, then who else does not know? Who does know? Who is taking action? I realized FGM/C was a topic about which I needed to learn more. I could not simply move on after understanding this information. Over the past year of my research on the topic, I became passionate about raising awareness of FGM/C, and also in advocating for women’s rights and raising awareness on violence against women. For my capstone project, I created a podcast to explain why FGM/C happens, to share women’s stories, to educate listeners on how to help, and to bring outside professional knowledge to help us better understand the topic. Through my research, I found Sahiyo–United Against Female Genital Cutting, and was impressed with their content and purpose. I reached out and asked if they would be willing to help me make this podcast possible. They were so gracious and introduced me to their network of individuals to ask if they would be willing to participate in my podcast. I was able to talk with some of the most incredible individuals and listen to experiences from people with different backgrounds. It was truly eye-opening and life-changing. I learned so much from my time interviewing everyone, and I am so grateful to Sahiyo for making it all happen. In addition to the podcast, I designed an exhibition displaying my research on FGM/C at Brigham Young University. For the exhibition, I created a poster series displaying facts about FGM/C by integrating a custom font that I created which has sharp characteristics throughout the posters. I also designed and installed a floral installation that symbolizes women. Flowers are beautiful and represent proud and glorious femininity and within the installation, each flower represents a woman. The hanging flowers represent women who have not been cut and the flowers on the ground represent the women who have been cut. Just because these flowers are not suspended from the ceiling does not lessen their value or their beauty in any way. They are still flowers but are just a little different. These women, like the flowers, are unique because they have been cut and have a piece of their body missing. But they are still just as powerful and beautiful. My hope through the exhibition was that individuals would feel moved to action and inspired to listen to the podcast to do their part in educating themselves and others on the topic to normalize the conversation so we can finally see it end.

Is the United Kingdom backing out of its commitment to end female genital cutting amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

By Olivia Bridge In the midst of a global pandemic set to the backdrop of Brexit, ending violence against women and girls (VAWG) appears to have slipped down the United Kingdom (U.K.) Government’s priority list. Yet, as campaigners and charities are acutely aware, abuse thrives in silence behind closed doors – and women and girls disproportionately pay the price. One form of abuse that charities fear is on the rise is female genital cutting (FGC), a practice which has affected more than 200 million women and girls worldwide, with a further 68 million more estimated to be at risk in the next ten years. It is said that every seven seconds, a girl somewhere around the world faces the potentially agonizing pain and trauma of being cut. What is FGC? The World Health Organisation defines FGC as a procedure which involves the “partial or total removal or the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” There are four types of FGC that vary in severity, but all types are recognised as child abuse and a violation of women’s and girls’ human rights. In some cases, anaesthetics and antiseptics aren’t used, meaning not only is the initial cutting procedure traumatic, potentially life-threatening and painful, but survivors are at increased risk of blood infections, hemorrhaging and infection throughout their lives, and can face issues with urination, menstruation, pregnancy and penetration. Communities who practice FGC claim it is linked to tradition, faith and ideas around gender roles, insisting girls must preserve their virginity. Many families believe FGC to be a rite of passage for their daughters, and in some communities, it can go hand-in-hand with other practices, such as breast ironing and forced marriage. FGC is a global issue involving at least 92 counties, including the U.K. Despite landmark legislation making those facilitating the practice to be punishable for up to 14 years in prison, girls born to families of these regions in the U.K. are at a heightened risk of being taken abroad under the false pretense of a special ceremony. How prevalent is FGC in the U.K.? In the mere five years that the U.K. has been recording data, 24,420 women and girls have been identified by the National Health Service (NHS) as having undergone FGC, with 6,590 being treated in the year up until March of 2020 alone. 205 victims or survivors were U.K.-born. In total, it is estimated 137,000 women and girls are living with its effects in England and Wales. But many believe the official figure to be the tip of the iceberg considering most survivors (80%) go undetected until they come into contact with midwives or obstetric services. But some women may never come into contact with the NHS at all, including women who don’t have Indefinite Leave to Remain or any form of secure immigration status, in part, either because they are unaware of the support available, or they fear immigration enforcement. What is the COVID-19 impact? However, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have ramped the practice around the globe. A policy briefing by the Orchid Project in September illuminates the extent, noting, “COVID-19 related lockdowns are being seen as an opportunity to carry out FGC undetected,” across East and West Africa; and “economic hardship is driving increased rates of FGC because of parents seeking ‘bride prices.’” Other research conducted by UNFPA anticipates that as a result of coronavirus disruptions to FGC prevention programmes, as many as two million more cases could take place in the next ten years that would otherwise have been avoided. As such, it estimates a one-third reduction in the progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating the practice by 2030. Campaigners attribute the rise to mass school closures, a decrease in access to support and health information, and the economic situation forcing girls into marriage for families to secure a dowry. Indeed, as joint research points to prove, whenever girls are stifled from education, they become increasingly more vulnerable to abusive practices. For this reason, campaigners fear the true scale of gender-based violence is yet to be realised as the U.K. creeps in and out of lockdown and restrictive measures are tweaked every few weeks. Kate Agha, the Chief Executive of Oxford Against Cutting, said, “With the rise in harmful traditions overseas, practicing-communities in the U.K. will come under increased pressure from family abroad to ensure they are part of the group and upholding cultural traditions based on honour.” What is the UK doing about it? The U.K. has remained determined to end FGC, setting a deadline to prevent it from occurring for good by 2030, in line with many other countries. Progress has been commendable. FGC has been outlawed in several Western countries including the U.K., Canada, Spain and New Zealand, among others, including 19 African countries. To date, the U.K. remains the largest donor to support the end of FGC globally, helping 10,000 African communities and assisting six African nations with a budget and new laws to criminalize it. However, amid these trying times, progress seems to be stalling and commitment stuttering behind if the U.K. is to realistically facilitate the end of FGC in the next ten years. For instance, despite being against the law for thirty-five years and a whole host of civil protections and laws being introduced in 2003, there has only been one successful prosecution, which took place in February of 2019. Meanwhile, charities claim social workers and even healthcare practitioners aren’t always trained and equipped to safeguard and handle victims or survivors with there being greater emphasis on support post-procedure than preventing it from happening in the first place. Due to a shocking knowledge gap in Lancashire hospices that emerged in August, medics are now receiving extra training. But how many more remain ill-equipped? Many believe the U.K. is silently withdrawing from its commitment altogether as it emerges that the Home Office has slashed funding from The National FGM Centre which, since its inception

Crying out our mothers’ grief: How we allowed female genital mutilation to flourish in our communities

By Tamanna Taher When I began writing an article on female genital mutilation (FGM), I was adamant that my research be thorough, and my opinions be carefully articulated. However, I did not realise the mammoth task the latter would become. It has been two years since I started writing this article. I was a sophomore in college when I began, and I sit here as a senior, writing to pledge my solidarity to end FGM. My parents had managed to shield me from the hushed conversations that I always knew were happening. I was 14 years old when I was finally let into the discussions recounting personal experiences and stories from survivors in the family. I remember sitting in the backseat of my parents’ car, asking what they were whispering about. My father said it was okay to tell me, and explained FGM, or khatna, as it is known in the Dawoodi Bohra community. “It is when a female is circumcised.” “Circumcised? How? What?” “They (carefully separating us and them), believe that for a woman to be pure, she must undergo a surgical procedure in which she is circumcised.” “Oh.” At this moment, I was as any teenager finding out about such an issue would be – very uncomfortable. Deciding not to ask anything else, I sat back and wondered what exactly was there to be circumcised down there. This went on for a few very silent weeks. However, I finally mustered enough courage to ask the question that had been haunting me. Had it been done to me? I remember awkwardly questioning my mum one day, asking whether I was so young that I did not even remember. She informed me that she was vehemently against it, and neither me, nor my sister, had this procedure done. She said she would never, as she was a victim of it herself: a victim of family traditions and beliefs, and another one of the countless victims of groupthink. She said that she remembered her experience, and it was not something a woman forgets. She was seven years old. My mum never called herself a victim. She told me that she had never understood it fully. At the time she drew a parallel between being cut and getting an ear piercing. That is why, she explains now, she never questioned her mother. That is why she believes her mother never questioned my great grandmother. She thought of it as a necessity of growing up – not a religious doctrine, but a cultural tradition. I have chosen the words victim and survivor very purposefully. I believe if this had truly been something she did not feel was an injustice to women around the world, my mother would have chosen us to carry the burden of the tradition. But she stepped back, separating herself from the powerful clutches of “Log kya kahenge?” (“What will people say?”) She saved her daughters from the injustice she was too young to save herself from. I will forever be grateful to my mother, for being so brave and standing up against members of the family she loved and trusted, fighting them and protecting us from the practice that she had to suffer from herself, of which countless others still have to suffer the consequences. I began asking the women around me whether they had been subjected to any form of FGM. I was appalled at how many of them said yes. I was even more revolted when I found out that my family had been divided by this issue. There were people around me that agreed with what was happening, so much so that they decided to boycott all the members of the family who saw FGM for what it was – child abuse. This was a confusing time for me. I was very close to a cousin of mine who defended the right to have been cut. She saw it as something that should be a choice. I was almost swayed by her. I regret that I allowed that to happen, and I am embarrassed that I did not realise sooner the repercussions of staying silent in such situations. I see now that khatna is not a choice. The girls who are cut are not consenting. They are usually ignorant about what is being done to them – realising the effects only in adulthood, and at which point they must silently bear the psychological pain and trauma. A girl, in the moment, might only feel the excruciating pain of the instrument being used to perform the procedure, but when she becomes a woman, she will realise that the cuts run deeper than what she previously thought. This is why so many people have begun to speak up. This is exactly why Sahiyo – United Against Female Genital Cutting as an organization exists. Children cannot make these decisions, and you cannot legally call them consenting beings. They do not have full knowledge, and they do not realise the gravity. To anyone who argues otherwise, I would like to present several stories. One of the women I spoke to told me that she had been promised ice cream if she went. She was only 8 years old; an adult would recognise that as manipulation. Another told me that her mother said she was going to see a doctor because she was sick. That is universally recognised as deceit. I even had someone tell me that her mother had slapped her and told her that she was doing this for God. That is plain and simple coercion. But, most importantly, all of the above is child abuse, manifesting in its verbal, emotional and physical forms. You might be thinking, but what will speaking up do? We need you to understand that every voice matters because we are speaking for those that had been stripped of theirs. You may also be thinking there is so much awareness. The number of girls subjected to this must be falling. That is far