Sahiyo Storycenter Workshop: The Power of Storytelling

Let there be no more victims like me

By AnonymousCountry: Sri Lanka I am a victim of Female Genital Cutting – some might want to call it circumcision, I call it Mutilation. Not quite the way that the proponents want to depict it as what always happens in Africa (infibulation) with horrific scars, but in the way, it happened to me in Sri Lanka where there are still scars, tiny, almost unnoticeable. But in all the ways that matter, it has damaged me no less than the most severe forms of mutilation. To those who want to medicalize the procedure, let me say that I was cut by a qualified doctor, in a sterile environment, when I was seven-years-old. I remember that day clearly and it is I who have had to live with the consequence of what was done to me in the name of religion. Not my religious leaders, not my elders, and not that doctor. ME, the woman who that child without a voice grew up to be. Let me now take the arguments I’ve heard in support of the procedure and give you my perspective as someone who has first-hand experience of the negative impacts of FGC. I will use the term female genital cutting (FGC) since irrespective of what one wants to call it, that is what is done to a lesser or greater degree, depending on who holds the pin, blade or knife. A. Sex lives as Adults To the women who say that they have better sex lives due to FGC, I ask you this: what is your point of reference? Have you had sex with the same partner before and after your FGC to arrive at this conclusion? Have you ever considered the possibility that you have been very lucky, and that whoever performed the FGC on you spared you any real damage? It is also very presumptuous for you to assume that NONE of the billions of uncircumcised women around the world enjoy great sex the same as you. To the women who don’t have a horrific memory related to their own FGC and who don’t understand what all the fuss is about: let me tell you that neither do I. I don’t have any horrific memories of that day. My Mom who accompanied me held me gently, the doctor looked very professional and it was over before I knew what was being done. I felt a pinch, no bleeding that I can remember – just some cotton wool that smelled of antiseptic placed there after I was cut. And I walked out, confused, uncomfortable but definitely not traumatized. Sounds familiar? It wasn’t until I was as an adult that I realized the impact of what was done to me. I feel pain during intercourse. Most of you may not. But does that mean you are not damaged? Have you ever considered the fact that intercourse is supposed to be more than just “pleasant” or something you put up with when your husband feels so inclined? In my case, I have been examined by a doctor who has seen the tiny scars and helped me understand the impact of those scars on my ability to enjoy sex. Initially, I wondered whether what happened to me was a mere unfortunate mistake by this doctor. I have since then come across stories of others in Sri Lanka who were cut by the same and other doctors who share similar tales. So no, I was not an unfortunate accident – the doctor and others like him/her knew exactly what they were doing and did it nonetheless. B. The need to perform the procedure on a child All the literature shared by the supporters of this practice alludes to adult women enjoying their sex lives. However, I still have yet to come across any argument to support as to why the procedure needs to be performed on seven-year-old girls who have a long way to go before they begin their sex lives. So, what is being promoted is, in fact, the sexualizing of children. News flash: these organs don’t stay dormant and get activated only when one gets married. Personally, I find the very idea of parents allowing strangers to access to their daughter’s private parts for non-medical reasons and letting them alter her genitals, an extremely troubling thought. I’m more inclined to believe that in their hearts, they know that they are in fact desexualizing her. What they want in reality is to keep her pure and innocent until she could be given away. There is no thought given to the fact that she then has to live with a damaged body and fulfill marital obligations that she may not enjoy as much in their effort to keep her pure and innocent until she was given away. C. The Religious Argument Who decides on one’s religious belief? The individual or the individual’s parent? Yes, the parents would bring up the child within the religious norms they follow, and yes in most cases the child would continue with that belief till the end, but this is not always true for everyone. Hence, how do you justify altering a child’s body, without any medical reason, to be in alignment with the parents’ religious belief, when that child is yet to determine what path she would take or which God she will follow once she has learned enough to make that decision? As for me, I don’t believe that the God who created me required any man or woman to tamper with my body, with the assumption that they can make it better. I believe the Quran when it says that all of God’s creations are perfect. I won’t let any man or woman tell me otherwise. But my body has been altered irrevocably – it’s no longer the way God created it to be. My body is now in conflict with my religious beliefs. It has ended up representing the beliefs of others and not mine. The religious belief of others has also denied me

A Tradition That Branded Me

Sharing My Story of Female Genital Cutting with Other Survivors Comforted Me

Sahiyo Stories – Women in the U.S. Share Stories on Female Genital Cutting

Sahiyo is excited to announce the launch of our digital story project: Sahiyo Stories! The project brought together nine women from across the United States to create personalized digital stories that narrate the experience of undergoing female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and/or the experience of their advocacy work to end this form of gender violence. [youtube url=”https://youtu.be/705aESUouik”] It was created and organized by Mariya Taher, co-founder of Sahiyo, and Amy Hill, Silence Speaks Director at StoryCenter. Over the course of the next 10 weeks, Sahiyo will be sharing one story a week created by the nine participants: Renee Bergstrom, Zehra Patwa, Maria Akhter, Salma Qumruddin, Maryah Haidery, Leena Khandwala, Severina Lemachokoti, and Mariya. Subscribe to Sahiyo’s YouTube channel to watch them all! Every woman who attended the workshop was facing her own challenge with FGC and was in a different phase of coming to terms with the practice. Some women had only recently discovered they had undergone FGC and were grappling with its emotional and physical impacts, while others were deeply invested in advocacy efforts to prevent it from happening to other girls. Though each digital story reflects a different perspective, the collection is woven together through shared experiences and a united sentiment. The women’s joint hope in creating and sharing these videos is to build towards reaching the critical mass of voices needed to prompt social change. They hope their stories demonstrate that there is an increasing trend of support for abandoning this harmful practice in every community where FGC occurs. If you are interested in learning more about the project or hosting a screening of Sahiyo Stories, contact mariya@sahiyo.com. We also welcome your support in promoting these videos among your social networks. For this first two weeks, we invite you to watch and share: “Making Sahiyo Stories” and “Shattered Silences.” To share the videos on social media, click links below:Twitter – http://bit.ly/2NS7oe0Facebook – http://bit.ly/SahiyoStories

Why I Chose to Tell My Story About Female Genital Mutilation at the Sahiyo Stories’ Workshop

The subject was heavy, but my heart felt light: My experience at Sahiyo’s StoryCenter workshop

To All of You Extraordinary Women Who Survived Female Genital Mutilation, You Are Strong

By: Nada QamberCountry: Kingdom of Bahrain The day I heard about Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), my jaw dropped. A friend of mine who has grown to become one my closest friends was a victim of this practice. When she told me, my heart broke. I never thought that any culture could do that to their little girls and think that it’s okay. Harming a woman’s gift from the universe is a practice that must be changed across the world. It’s an awful experience to go through at such a young age. Today, I’m not going to bash the cultures that practice this, but praise its strong survivors. I don’t know much about the communities that practice this requirement, nor do I purely understand their reasons behind it, but I know enough to support the idea that young girls should grow up without experiencing pain like this. Children shouldn’t have to block a horrific memory from their minds and get flashbacks of it later in their lives. So, I praise you, my fellow women. You have gotten your stems cut off while you were just a flower bud and were left to grow up with a scar that didn’t make sense for so many years. You are still growing. I praise you, my fellow females. You have gone through a dreadful experience that your mothers forced upon you, and cried until your lungs were sore. You have a voice. I praise you, my fellow ladies. You fought your mothers, your grandmothers, your aunts, and the person who did this to you. You have courage. I praise you, my fellow badass warriors. You know that you cannot change what happened to you but you are fighting to change the lives of young girls after you. You are fierce. Finally, I praise you, fellow beauties, for your growth, your voice, your courage, and your strength to fight to change the minds of the force-makers, the religious leaders, the head of the household, and most of all, fight for the lives of young girls. You have power. Coming in as an outsider who was fortunate to be spared from this practice, my heart goes out to all of you who went through this experience, and I pray that all of us together are strong enough to make a change and let future girls live a fruitful childhood.

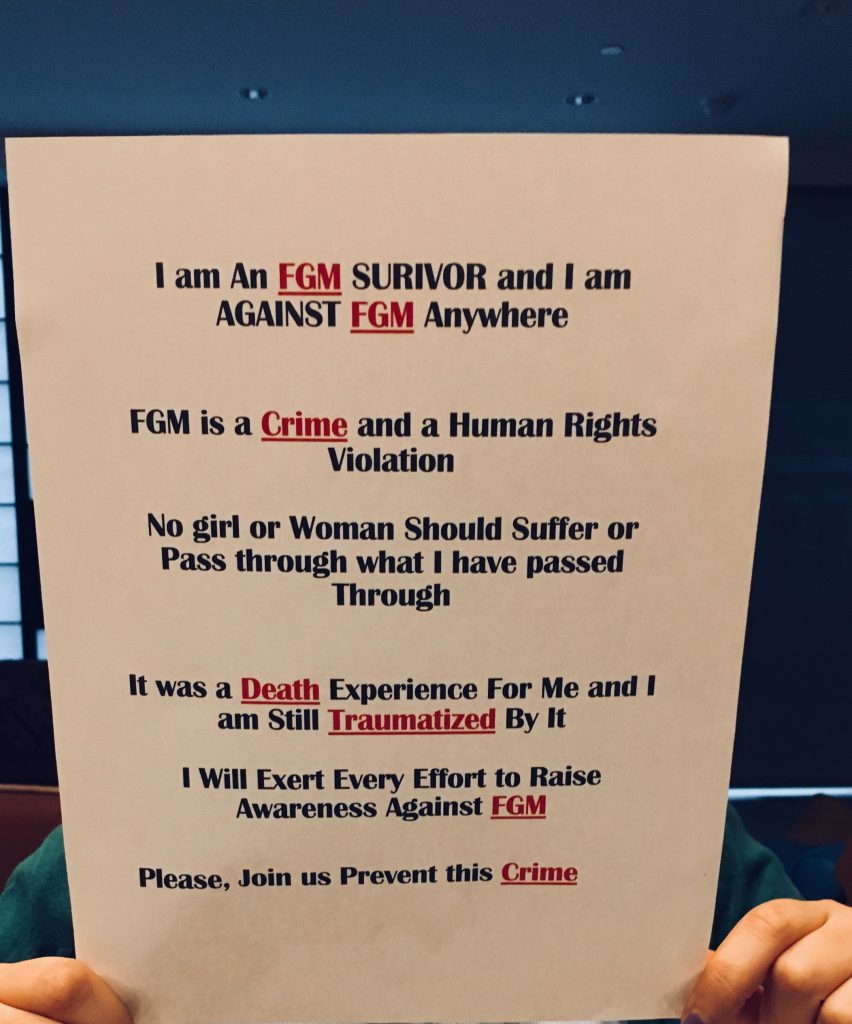

I Said It Loudly: I am an FGM Survivor. Meeting FGM Survivors for the First Time Was My Cursed Blessing

(Note: The following blog was written by a survivor who attended a meeting, the topic of which was on mental health and FGC. Her story highlights the power of storytelling and how it helps break the isolation that many survivors experience in having undergone FGC and dealing with their trauma afterwards, an isolation that Sahiyo is attempting to break via the storytelling work we engage in with communities.) By Anonymous Country: Egypt & United States Even now, despite my brain trying to convince me it was a good idea to attend a conference on FGM and Mental Health, I cannot emotionally explain what really happened that day. The conference consisted of FGM survivors, human rights advocates, therapists, and policymakers, and almost two weeks after having attended, I started to have stronger flashbacks of the terrible experience I underwent with FGM in my home country, Egypt. I have mixed feelings of love, support, and pain for having attended that conference. My journey dealing with that horrible experience started in my home country where my rights as a human being were violated without my consent. I was bleeding and almost died having been operated upon twice. Even now, I cannot easily write these words. You may wish to read my full story published here. The experience of meeting with other survivors from India and other countries was something I strongly needed to help bring me face to face with the many answers to the many questions in my mind regarding why I experienced so much anxiety, sadness, depression, panic, and fear after my cutting. I wanted to know how other survivors had dealt with their FGM especially those who spoke up about it publicly, such as (Mariya Taher, Leyla Hussien, Jaha Dukureh , Naima Abdulhadi, and others) ; I am relatively new to openly talking about it and I still feel as if I am climbing a mountain when trying to share or speak about it. I heard these women saying how it was and is still difficult; and listening to them has helped me to feel that I am not alone in my experience. I saw how powerful the pain of this experience can be, but at the same time was inspired by the courage of what they and I were determined to do. To speak up about FGM openly and to try to prevent it from happening to other girls. That meeting was the first time I met with and spoke to other survivors from different countries, such as the United Kingdom, Gambia, India, not to mention the United States. At the time, I felt happy that this meeting could serve as a comfort zone for me, knowing others understood what I had gone through. Seeing all those women in that room encouraged me to say amongst the group of almost forty members that I too am a FGM SURVIVOR. I knew these women would not shame me and I did not need to fear being labeled, judged, or threatened for publicly admitting I was a survivor. My heart was beating and my breath was short as if I had climbed a mountain. I thought I was ok during the 8-hour meeting, yet I collapsed and burst into tears at the end; I cannot precisely tell you why, but I thought about how it is unfair that our bodies and souls are violated with this harmful crime. Most of the time I feel sad that I had to go through these painful thoughts, feelings, or flashback of the operation room and after. It feels like I am being retraumatized when something happens to trigger the original trauma of FGM. I beg every mom and dad to see their daughters as beautiful souls who do not need to be cut to be pure. I am Muslim, and I can say it strongly, clearly, and angrily: Do not make it religious because it is not. My body was not supposed to be violated in this severe way nor was my soul. Yet, both happened. But I am comforted in knowing that there are others who I can talk to who understand my pain. FGM is a crime and more work needs to be done with healthcare professionals, as well as policy makers. Girls must be protected from being cut and survivors should be supported with the needed assistance to help them heal.

The undecided: Conversations with survivors of Female Genital Cutting in Pakistan

By Hina Javed(This is the fourth part in a series of essays by Hina Javed on her experience of reporting on FGC in Pakistan. Read the whole series here: Pakistan Journal.) My conversations with survivors had by now made it clear that the more answers I received, the more questions arose. Wrapping my head around Female Genital Cutting (FGC) was not going to be easy as I had, up till that point, been presented with two extreme views of FGC with little room for middleground.I found myself diving deeper to uncover the truth behind a practice which spanned centuries; a curiosity fuelled my quest to get to the very origins of such an invasive practice. From the outside, the Bohra community seemed united, but I found the more I scratched at the community’s surface, the divisions and differences of opinion on FGC became evident. Publicly, the Bohra community will protect their own; quietly, they dissent amongst themselves. Getting to the bottom of this practice had become more than an assignment for me. The following day I found myself sitting in the drawing room of an elderly lady who belonged to the Bohra community in Karachi. Here was 65-year-old Mrs Sumaira*, ready to answer all my questions without a hint of doubt or hesitation: “Aunty, what is your opinion on female circumcision? Is it right or wrong?” “Well, I cannot comment on the moral and legal implications of the practice. It is not for me to decide. All I know is that circumcision is sanctioned by our community leader. I am not entirely sure if it is right or wrong, but I believe the decision should be left with the child,” said Mrs Sumaira. “What about you? Did you get your daughter circumcised? Did you inform her prior to her circumcision? How did you feel when she was finally cut?” I asked without bothering to check my train of thought or questioning. “I was in my early thirties when the pressure to get my little one cut started building inside me. I knew it was supposed to happen sooner or later. I feared a backlash from the family elders if I delayed it any further. It was a rite of passage and my daughter had to go through it. My only, and probably biggest fault, was not telling the truth to an innocent child who thought she was going to a lady doctor for a routine check up. I told her they might perform a small operation if they found a ‘bug’ down there. I deeply regretted lying to her when I saw her bleeding and in pain,” she told me somberly. “Why did you regret? Was it only the pain that made you feel guilty or was it something else?” I asked. The answer she gave me came ridden with doubt. Sumaira believed she had little choice all those years ago. “Maybe this wasn’t the right thing to do. Maybe I took something away from her; something that actually belonged to her the minute she opened her eyes. I could have given it a second thought, but I was overwhelmed with uncertainty and wanted to get it out of the way. I knew I would get a lot of raised brows if I avoided it altogether. In fact, I would have been ostracised from the community,” she added. My line of questioning had ruffled some feathers, and I became more determined to seek answers. “Aunty, forgive me if I am being too intrusive, but didn’t you say you believed it was a necessary rite of passage?” Sumaira explained that the decision she took for her daughter, without the latter’s consent, was in the girl’s best interest. “I believe it depends on the type of society you live in and the level of exposure you get growing up. It’s true that circumcision lowers the libido and you have no right to take that away from an individual. However, it becomes necessary to control that drive if the girl is growing up in a conservative society like Pakistan. If she goes ‘astray’, she would be called names and looked down upon. Besides, she would also have to suppress her desires which could ultimately lead to psychological issues like depression and anxiety,” she said. “Does that mean it is more of a social requirement than a religious ritual in the Bohra community?” I asked, confused. Sumaira’s reply made it clear she was also confused. “It could be, but I am not entirely sure about that. I believe it’s good if you get it done. However, there is an element of choice which people did not realise back in the day. People who are growing up in a free society and have liberal mindsets could either do away with it or let their child decide.” Sumaira continued to speak but her response left a deafening silence from me. It became difficult to detach myself emotionally and focus on that interview. Therefore, I targeted my final question at just that; breaking the silence. “Then why do you think breaking the silence will help? Why did you decide to speak about this issue in the first place? How will it change the narrative?” I asked apprehensively. “It’s just the question of expressing yourself. If you disagree with the practice, you should be able to voice your opinion without being bashed by others. And if you want to go for it, then there’s no one stopping you. In either case, there’s no reason for it to be a hush-hush affair. There is more awareness, education and freedom of expression in this day and age. You’re free to make your own decision,” she concluded. The hour-long question and answer session with Sumaira left me more confused than before. My search for the right answer was becoming fruitless with every interview, but, in the midst of it all, I realised that three categories of people existed in the Bohra community when it came to FGC: the decided, the