Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 6: Effects of FGM/C on the Lower Urinary Tract System

(This article is Part 6 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Julia Geynisman-Tan, MD Background FGM/C has no known health benefits, but does have many immediate and long-term health risks, such as hemorrhage, local infection, tetanus, sepsis, hematometra, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, obstructed labor, severe obstetric lacerations, fistulas, and even death. While the psychological, sexual, and obstetric consequences of FGM/C are well-documented (refer to prior posts in this series), there are few studies on the urogynecologic complications of FGM/C. Urogynecology is the field of women’s pelvic floor disorders including urinary and fecal incontinence, dysfunctional urination, genital prolapse, pelvic pain, vaginal scarring, pain with intercourse, constipation and pain with defecation and many other conditions that affect the vagina, the bladder and the rectum. Urogynecologists are surgeons who can both medically manage and surgically correct many of these issues. FGM/C and Urinary Tract Symptoms One recent study from Egypt suggested that FGM/C is associated with long-term urinary retention (sensation that your bladder is not emptying all the way), urinary urgency (the need to rush to the bathroom and feeling that you cannot wait when the urge comes on), urinary hesitancy (the feeling that it takes time for the urine stream to start once you are sitting on the toilet) and incontinence (leakage of urine). However, the women enrolled in this study were all presenting for care to a urogynecology clinic and therefore all of them had some urinary complaints so it is difficult to tell from this study what the true prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms are in the overall FGM/C population. Therefore, given the significant number of women with FGM/C in the United States and the paucity of data on the effects of FGM/C on the urinary system, my research team studied this topic ourselves in order to describe the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in women living with FGM/C in the United States. Publication will be available online in December 2018. We enrolled 30 women with an average age of 29 to complete two questionnaires on their bladder symptoms. Women in the study reported being circumcised between age 1 week and 16 years (median = 6 years). 40% reported type I 23% type II 23% type III 13% were unsure Additionally, 50% had had a vaginal delivery; and 33% of these women reported that they tore into their urethra at delivery. Findings: A history of urinary tract infections (UTIs) was common in the cohort: 46% reported having at least one infection since being cut 26% in the last year 10% reported more than 3 UTIs in last year 27% voided ≥ 9 times per day (normal is up to 8 times per day) 60% had to wake up at least twice at night to urinate (once, at most, is normal) Most of the women (73%) reported at least one bothersome urinary symptom, although many were positive for multiple symptoms: urinary hesitancy (40%) strained urine flow (30%) intermittent urine stream (a stream that starts and stops and starts again) (47%) were often reported 53% reported urgency urinary incontinence (leakage of urine when they have a strong urge to go to the bathroom) 43% reported stress urinary incontinence (leakage of urine with coughing, sneezing, laughing or jumping) 63%reported that their urinary symptoms have “moderate” or “quite a bit” of impact on their activities, relationships or feelings What’s the Connection Between FGM/C and Urinary Symptoms? Urinary symptoms like the ones described above can be the result of a number of factors. Risk factors for urinary urgency and frequency, incontinence, and strained urine flow include pregnancy and childbirth, severe perineal tears in labor, obesity, diabetes, smoking, genital prolapse and menopause. However, given the average age of women in our sample and the fact that only half of them had ever had a vaginal birth, the rate of bothersome urinary symptoms are significantly higher than has been previously reported. FGM/C may be a separate risk factor for these symptoms. Interestingly, the prevalence of urinary tract symptoms in our patients closely resembled that of a cohort of healthy young Nigerian women aged 18-30, in which the researchers reported a prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms of 55% with 15% reporting urinary incontinence and 14% reporting voiding symptoms. The authors do not mention the presence of FGM/C in their study population but the published prevalence of FGM/C in Nigeria is 41%, with some communities reporting rates of 76%. Therefore, it is likely that many of the survey respondents had experienced FGM/C, thereby increasing the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in their cohort. In the study of women in Egypt referenced above, those with FGM/C were two to four times more likely to report urinary symptoms compared to women without FGM/C. The connection between FGM/C and urinary symptoms can be understood from the literature on childhood sexual assault and urinary symptoms. Most women who experience FGM/C recall fear, pain, and helplessness. Like sexual assault, FGM/C is known to cause post-traumatic stress disorder, somatization, depression, and anxiety. These psychological effects manifest as somatic symptoms. In studies of children not exposed to sexual abuse, the rates of urinary symptoms range from 2-9%. In comparison, children who have experienced sexual assault have a 13-18% prevalence of enuresis (bedwetting) and 38% prevalence of dysuria (pain with urination). The traumatic imprinting acquired in childhood persists into adult years. In a study of adult women with overactive bladder, 30% had experienced childhood trauma, compared to 6% of controls without an overactive bladder. There is a neurobiological basis for this imprinting. Studies in animal models show that stress and anxiety at a young age has a direct chemical effect on the voiding reflex and can cause an increase in pain receptors in the bladder. Additionally, the impact of sexual trauma on pelvic floor musculature has been well described. Women who

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 5: The “C” Word… and I Don’t Mean Circumcision

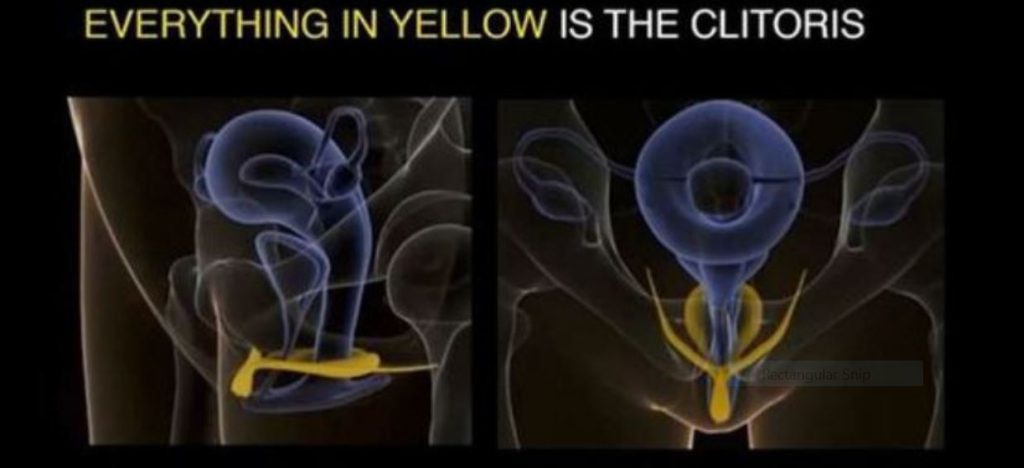

(This article is Part 5 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Since the ritual of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) involves the clitoris, it seems important to learn more about this organ and its function. But first a bit of history, or—more appropriately—herstory. In over 5 million years of human evolution, only one organ exists for the sole purpose of providing pleasure — the clitoris. Yet, from ancient times to the present, the anatomy of the clitoris has been discovered, repressed, and rediscovered. Hippocrates, the Greek physician, born circa 460 B.C., called the clitoris “columella”: the little pillar. About 500 years later, Galen, an anatomist renowned in Rome, denied its existence. Centuries later, the 1901 edition of Gray’s Anatomy included a drawing of the female pelvis in cross-section, showing a small protrusion with the label “clitoris” (Gray, 1901). In the 1948 edition of Gray’s Anatomy, there is an analogous illustration of female genital anatomy (Goss, 1948). Yet, the label of the clitoris is now gone. The clitoral protrusion of the older illustration is also removed. As a result, the clitoris has now been erased (Moore & Clarke, 1995). Just The Tip of The Clitoris In reality, what we generally think of as the clitoris—what we can see and feel—is just the pea size tip of the clitoris, called the “glans”. The glans, located at the top of a woman’s vulva, at the point where the labia majora meet (near the pubic bone), contains approximately 8000 sensory nerve fibers—more than anywhere else in the human body. In fact, the amount of sensory nerve fibers in the glans is twice the amount found on the head of a penis. More Than Meets The Eye Many people assume that all there is to the clitoris is the glans, but with the clitoris, what you see is not what you get. Helen O’Connell, an Australian urologist, and her colleagues have corrected that misconception (O’Connell, Sanjeevan, and Hutson, 2005). Using modern imaging techniques such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), O’Connell has shown that there is much more to the clitoris than what meets the eye. They discovered that the glans of the clitoris is simply the tip of an extensive organ. In fact, three-quarters of the clitoris is inside the body. As shown below, the clitoris is a wishbone-shaped structure that is about 3 ½ in. (9 cm) in length and 2 ½ in. (6 cm) in width. The glans extends backward into the clitoral body. The glans then split into the two leg-like parts, the crura, which are composed of erectile tissue and are next to the vagina and urethra (see MRI photo below of internal clitoris). The vestibular bulbs are two elongated masses of erectile tissue situated on either side of the vaginal opening. The Clitoris and Its Place within the Vulva The vulva is a single term used to describe all the external female genital organs. These organs include the labia majora, the labia minora, the clitoris, the vestibule of the vagina, the bulb of the vestibule, and the glands of Bartholin. The two sets of labia (lips) form an oval shape around the vagina. The labia minora are smaller and surround the vagina. The labia majora are larger, and, after puberty, the outer part of the labia majora is covered with pubic hair. Since there are large portions of the clitoris extending through the pubic area, sexual responsiveness is not limited to direct or indirect stimulation of the clitoral glans (Wallen and Lloyd, 2011). Due to this extended internal structure, the clitoris can respond to stimulation of the external vaginal labia, the vagina itself, and the anus. As a woman draws closer to orgasm, the clitoris can swell by 50 percent to 300 percent. According to O’Connell, “The vaginal wall is, in fact, the clitoris.” If you lift the skin of the side walls of the vagina you will find the bulbs of the clitoris (O’Connell 2008). O’Connell proposed the notion that during vaginal intercourse it is the “clitoral complex” that is stimulated. Clitoral anatomy and FGC: Removing the glans of the clitoris does not mean the whole organ is destroyed. The issue of clitoral anatomy is also significant concerning the practice of clitorectomy. Type 1 FGC: Often referred to as clitoridectomy, is the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in some cases, only the prepuce or hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris). The clitoral hood varies in size, shape, thickness, and other aspects of its appearance from woman to woman. Some women have large clitoral hoods which appear to cover the clitoral glans. Others have much smaller hoods which leave the clitoral glans exposed. While the biological function of the clitoral hood is simply to protect the clitoral glans from friction and other external forces, this body part is also an erogenous zone. It provides natural lubrication, which makes stimulation of the clitoral area more pleasurable. As the clitoral glans itself is often too sensitive to touch, many women gain pleasure from having the glans indirectly stimulated through the clitoral hood. Although female sexual pleasure is often hindered by clitoridectomy, many women report that they are still able to enjoy sex (Lightfoot-Klein, 1989, Kelly and Hillard, 2005). One researcher has found that even infibulated women may still have the ability to achieve orgasm. Dr. Lucrezia Catania, who has studied and treated FGC-affected women in Italy for two decades, has found that when some of the sensitive tissue of the labia minora and clitoris remain intact, infibulated women can experience orgasm, while others cannot and instead feel pain. Pelvic Nerve The clitoris has enormous potential for arousal, but what may affect sensitivity is the supply of nerve endings and the individual pattern of each clitoris, which explains the variation in women’s preference for stimulation. The pelvic nerve

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 4: Psycho-sexual functioning

(This article is Part 4 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA When discussing psychosexual functioning following FGC, it is critical to acknowledge and recognize that many women who have undergone FGC will not experience sexual health problems. It is also important to note that many women with intact genitals do experience sexual difficulties. Female sexuality is a complex integration of biological, physiological, psychological, sociocultural and interpersonal factors that contribute to a combined experience of physical, emotional and relational satisfaction. Nevertheless, symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can interfere across the continuum of sexual behavior affecting desire, arousal, physical and/or psychological pleasure. The amygdala is the organ in the brain that alerts us to possible danger and responds to the danger by triggering the fear response along with the release of the stress hormones. A state of negative hyperarousal persists for those who have been re-triggered by some person, place or memory associated to the original trauma while suffering from PTSD (see The Body and The Brain). For some women affected by Female Genital Cutting (FGC), re-traumatizing triggers can be their initial (and ongoing) sexual experiences. Not only can the physical position (identical to that required for FGC) induce a flashback, but the already traumatized genital area can feel repeatedly violated with sexual activity, gynecological exams—or childbirth itself. [Note. in Sahiyo’s Exploratory Student on FGC in the Bohra community, 108 women reported that their FGC (khatna) had adversely affected their sex life – See Graph below] When these flashbacks occur the brain’s fear circuitry takes over and the hippocampus can no longer communicate effectively with the amygdala to allay its fears. This condition often leaves those affected feeling emotionally charged with generalized fear(s) that persist even after the traumatic event has passed. (See also ‘The Clitoral Hood – A Contested Site’) There are 3 primary psycho-sexual complications commonly associated with FGC: painful intercourse (may be due to narrowing of vaginal canal; or excessive scarring, or clitoral neuromas, or infibulation or chronic infection); difficulties reaching orgasm; and, absence or reduction of sexual desire. Sexual difficulties can occur because for FGC survivors, positive sexual arousal mimics the physiological experience of fear. Once these hormonal and neuroanatomical associations have been forged through the intense experience of trauma and the associated PTSD symptoms, it can be difficult to uncouple them. In these instances, arousal frequently signals impending threat rather than pleasure. Thus, the biology of PTSD primes an individual to associate arousal with trauma and this impairs the ability to contain the fear response—which in turn impedes sexual functioning and intimacy. Due to repeated pain during sexual activity, women may develop anxiety responses to sex that restrict arousal and increase frustration—all of which can contribute to vaginal dryness, muscular spasm, painful intercourse and/or orgasmic failure. Women may actively avoid sexual activity to minimize feelings of physical arousal or vulnerability that could trigger flashbacks or intrusive memories. Others have reported that merely the fear of potential pain during intercourse and the frustration around delayed sexual arousal contributes to the lack of sexual desire. Recurring pain triggers memories adversely affected by the cutting. Chronic pain and distasteful memories reinforce each other and create a situation of mutual maintenance. Emotional and/or physical pain during intercourse diminishes the enjoyment of both the woman and her partner. Complications such as these can contribute to feelings of worthlessness, inhibit social functioning and increase isolation. In fact, many women have expressed feelings of shame over being different and ‘less than’. Some may experience their circumcised genitals, now deemed ‘different’, as shaming. Others may feel responsible for the relationship distress that results and carry a burden of guilt for being unavailable to “provide” sex. They may perceive their anxiety and difficulty about permitting penetration as something they must overcome. The psychological issues for younger women who have undergone FGC and are living in Westernized societies may be especially complex. These women (and their partners) are subjected to different discourses of sexuality that centralize erotic pleasure and frame orgasm as the endpoint of sex for women and men. Some women may struggle with what are deemed irretrievable losses. Feelings of aversion may extend beyond sex to physical closeness or even intimate relationships in general. In other situations, a woman may feel inferior to other women or less entitled to positive relationships, so that she may engage in an unsatisfactory or even damaging relationship which could further diminish her self-esteem. Another underlying belief behind FGC is that women’s genitals are impure, dirty or ugly if uncut. As a result of this perception, the female body is viewed as flawed—forcing women to modify their physical appearance to fit standards far removed from health, well-being and gender-equality objectives. Unfortunately, the very nature of this subject often doesn’t allow for much insight, since FGC has always been shrouded in secrecy. Women may be reluctant to disclose because of the fear of being judged, since FGM/C is perceived by outsiders to be illegal, and abnormal. The belief that sexual matters are to be kept private also makes FGC-affected women inclined to keep quiet about their symptoms and suffer in silence or attribute their pain to other sources. However, healing from the trauma through talk therapy as well as open discussions about strategies for obtaining sexual pleasure after FGC can be critical for women to regain control of their sexual identity. For more information about the Psychosexual Consequences affecting the Clitoris see Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 5: The “C” Word…and I Don’t Mean Circumcision. About Joanna Vergoth: Joanna is a psychotherapist in private practice specializing in trauma. Throughout the past 15 years she has become a committed activist in the cause of FGC, first as Coordinator of the Midwest Network on Female Genital Cutting, and most recently

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 3: The Body and the Brain

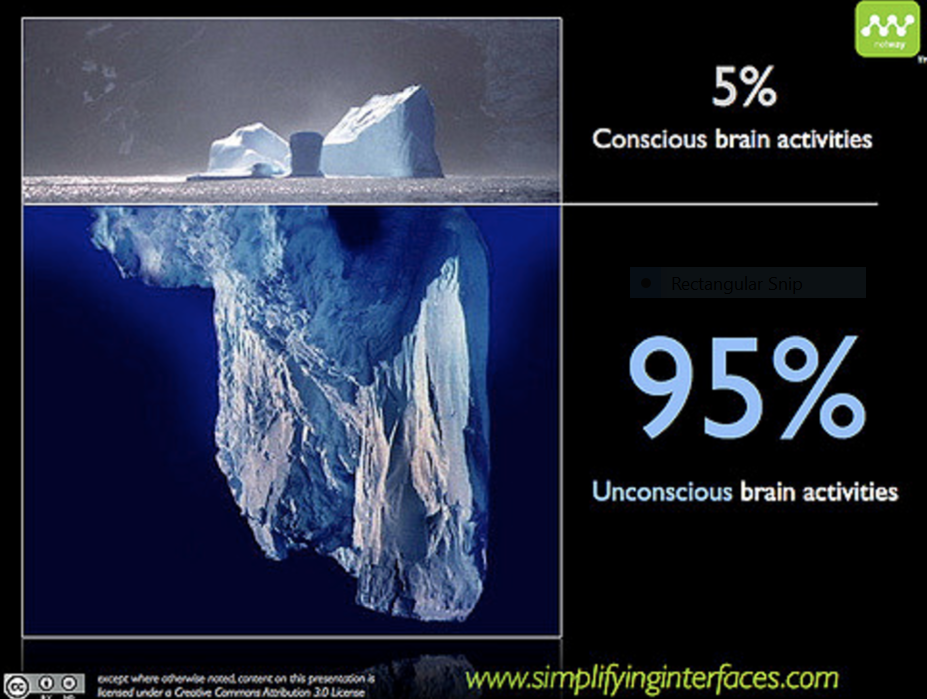

(This article is Part 3 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Trauma overwhelms us and disrupts our normal functioning, impacting both the brain and body, both of which interact with one another to regulate our biological states of arousal. When traumatized, we lose access to our social communication skills and displace our ability to relate/connect/interact with three basic defensive reactions: namely, we react by fighting, fleeing, or freezing (this numbing response happens when death feels imminent or escape seems impossible). In order to understand and appreciate our survival responses, it’s important to have a basic understanding of how our brain functions during a traumatic experience, such as undergoing Female Genital Cutting or FGC. Our brains are structured into three main parts: The human brain, which focused on survival in its primitive stages, has evolved over the millennia to develop three main parts, which all continue to function today. The earliest brain to develop was the reptilian brain, responsible for survival instincts. This was followed by the mammalian brain (Limbic system), with instincts for feelings and memory. The Cortex, the thinking part of our brain, was the final addition. The Reptilian brain: The reptilian brain, which includes the brain stem, is concerned with physical survival and maintenance of the body. It controls our movement and automatic functions, breathing, heart rate, circulation, hunger, reproduction and social dominance— “Will it eat me or can I eat it?” In addition to real threats, stress can also result from the fact that this ancient brain cannot differentiate between reality and imagination. Reactions of the reptilian brain are largely unconscious, automatic, and highly resistant to change. Can you remember waking up from a nightmare, sweating and fearful—this is an example of the body reacting to an imagined threat as if it were a real one. The Limbic System: Also referred to as the mammalian brain, this is the second brain that evolved and is the center for emotional responsiveness, memory formation and integration, and the mechanisms to keep ourselves safe (flight, fight or freeze). It is also involved with controlling hormones and temperature. Like the reptilian brain, it operates primarily on a subconscious level and without a sense of time. The basic structures of Limbic system include: thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus The Neocortex: The neocortex is that part of the cerebral cortex that is the modern, most newly (“neo”) evolved part. It enables executive decision-making, thinking, planning, speech and writing and is responsible for voluntary movement. But… Almost all of the brain’s work activity is conducted at the unconscious level, completely without our knowledge. While we like to think that we are thinking, functioning people, making logical choices, in fact our neocortex is only responsible for 5-15 % of our choices. When the processing is done and there is a decision to make or a physical act to perform, that very small job is executed by the conscious mind. How the brain responds to Trauma The fight or flight response system — also known as the acute stress response — is an automatic reaction to something frightening, either physically or mentally. This response is facilitated by the two branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) which work in harmony with each other, connecting the brain with various organs and muscle groups, in order to coordinate the response. Following the perception of threat, received from the thalamus, the amygdala immediately responds to the signal of danger and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated by the release of stress hormones that prepare the body to fight or escape. It is the SNS which tells the heart to beat faster, the muscles to tense, the eyes to dilate and the mucous membranes to dry up—all so you can fight harder, run faster, see better and breathe easier under stressful circumstances. As we prepare to fight for our lives, depending on our nature and the situation we are in, we may have an overwhelming need to “get out of here” or become very angry and aggressive (See ‘I underwent female genital cutting in a hospital in Rajasthan’ on Sahiyo’s blog). Usually, the effects of these hormones wear off only minutes after the threat is withdrawn or successfully dealt with. However, when we’re terrified and feel like there is no chance for our survival or escape, the “freeze” response, activated via the parasympathetic nervous system, can occur. The same hormones or naturally occurring pain killers that the body produces to help it relax (endorphins are the ‘feel good’ hormones) are also released into the bloodstream, in enormous amounts, when the freeze response is triggered. This can happen to people in car accidents, to sexual assault survivors and to people who are robbed at gunpoint. Sometimes these individuals pass out, or mentally remove themselves from their bodies and don’t feel the pain of the attack, and sometimes have no conscious or explicit memory of the incident afterwards. Many survivors of female genital cutting have reported fainting after being cut. Other survivors have reported blocking out their experiences of being cut (See ‘I don’t remember my khatna. But it feels like a violation’). Our bodies can also hold on to these past traumas which may be reflected not only in our body language and posture but can be the source of vague somatic complaints (headaches, back pain, abdominal discomfort, etc.) that have no organic source. FGC survivors who were cut at very young ages can be plagued with ambiguous symptoms such as these. Neuroscientists have identified two different types of memory: explicit and implicit. The hippocampus, the seat of explicit memory, is not developed until 18 months. However, the implicit memory system, involving limbic processes, is available from birth. Many of our emotional memories are laid

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 2: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

(This article is Part 2 of a seven-part series on trauma related to FGC. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Post-Traumatic Stress is the name given to a set of symptoms that persist following a traumatic incident and may be especially severe or long when the stressor has been of human design, such as in a violent personal/sexual assault (as in rape, torture, or Female Genital Cutting). These symptoms, which recreate the physical reliving of the trauma, can affect the way we think, feel and behave and, if experienced frequently, the condition that develops is called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a complex psycho-biological condition that develops differently from person to person because everyone’s nervous system and tolerance for stress is a little different. While you’re most likely to develop symptoms in the hours or days following a traumatic event, it can sometimes take weeks, months, or even years before they appear. The specific symptoms of PTSD can vary widely between individuals, but generally fall into the categories described below . Re-experiencing Re-experiencing is the most typical symptom of PTSD and occurs when a person involuntarily and vividly re-lives the traumatic event in the form of a flashback. Flashbacks appear as memories or fragments of memories from recent or past events and can leave you feeling fearful, confused and distressed. Jarring and disruptive, they can last a few brief seconds or involve extensive memory recall. Below are the categories and some examples of flashbacks: Visual Memories: various related images Auditory Memories: sounds of breathing, doors shutting, footsteps. Emotional Memories: feelings of distress, hopelessness, rage, terror or a complete lack of feelings (numbness). Body Memories: physical sensations like genital pain, nausea, gagging sensation, difficulty swallowing, feeling of being held down. Sensory Memories: of certain odors (e.g. perfume, body odor, alcohol) or tastes (e.g. sweat, blood). For some women affected by Female Genital Cutting (FGC), re-traumatizing triggers can be their initial (and ongoing) sexual experiences. Not only can the physical position (identical to that required for FGC) induce a flashback, but the already traumatized genital area can feel repeatedly violated with sexual activity, gynaecological exams or childbirth itself. Flashbacks can be accompanied by the same physiological reactions experienced at the time of the trauma, such as dizziness, rapid heartbeat, or sweating. In response to these distressing memories people can develop breathing difficulties, experience disorientation, muscle tension, pounding heart, shaking. Hyperarousal Trauma is stress run amuck. It dis-regulates our nervous systems and distorts our social awareness—displacing social engagement with defensive reactions. This state of mind is known as hyperarousal and often leads to: Irritability; angry outbursts sleeping problems; nightmares difficulty concentrating In severe cases, many have trouble working or socializing and may engage in reckless behaviors (driving too fast; being argumentative or provocative). Others with PTSD may feel chronically anxious and find it difficult to relax or concentrate. Also, problematic for many is difficulty falling or staying asleep or suffering from nightmares; feeling always anxious and on edge (referred to as hypervigilant) –they may easily be startled. Feeling afraid is a common symptom of PTSD and having intense fear that comes on suddenly could mean you are having a panic attack. It can happen when something reminds you of your trauma, and may trigger fearing for your life or losing control. Although anxiety is often accompanied by physical symptoms, such as a racing heart or knots in your stomach, what differentiates a panic attack from other anxiety symptoms is the intensity and duration of the symptoms. Panic attacks typically reach their peak level of intensity in 10 minutes or less and then begin to subside. Negative emotional states Some FGC-affected women may feel betrayed and develop problematic relationships with their mother, or female authority figures, and suffer from low self-esteem and concerns about body image. In addition, traumatized girls and women may develop persistent negative emotional states (e.g. fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame) and engage in distorted thinking such as “I am bad,” “No one can be trusted,” “The world is completely dangerous place.” In Sahiyo’s online survey of Dawoodi Bohra women, conducted in 2015-16, 48% of the women who had undergone FGC reported that the experience of FGC (khatna) left an emotional impact on their adult life. This impact included feelings of being haunted/traumatized by the memory of being cut, feeling betrayed and violated by the family, feelings of distrust towards them, as well as anger and fear. Avoidance and emotional numbing Trying to avoid being reminded of the traumatic event is another key symptom of PTSD. Individuals may try to block out the anxiety or fear associated with the distressing emotional feelings, by avoiding places, people and situations reminding them of the original traumatic experience. For example, the possibility of seeing the “cutter” in a social gathering may be very distressing and re trigger re-traumatization. (See A Pinch of Skin documentary by Priya Goswami). Some people attempt to deal with their feelings by trying not to feel anything at all. This is known as emotional numbing. Many people with PTSD try to push memories of the event out of their mind, often distracting themselves with work or hobbies. Others may engage in self-destructive behaviors (drug or alcohol abuse; eating disorders) in order to distract or numb themselves to feelings that are too painful to tolerate. Those feeling detached and numb often have trouble showing or accepting affection and, becoming isolated and withdrawn, may lose interest in people or activities they used to enjoy. Dissociation is a mental process that causes a lack of connection in a person’s thoughts, memory and sense of identity. It is a normal reaction to trauma and can help cut off the pain, horror and terror for a person experiencing mortal danger; an attempt to be “outside” the events (outside of oneself; besides oneself) happening rather than “inside”

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 1: What is trauma?

(This article is Part one of a seven-part series on trauma related to FGC. This article should not be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Many women who have undergone FGC may not have any lasting disturbances. But based on the Sahiyo study alone (see pie-chart below), there are those who may benefit from a deeper understanding of the effects of trauma. Often, we minimize, dismiss or normalize our symptoms and resign ourselves to feeling/living compromised. Learning more about trauma can provoke conversation; help one to feel less isolated and can prompt one to seek professional help. What is trauma? A traumatic event is defined as direct or indirect exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence. The incident may be something that threatens the person’s life or safety, or the life of someone close to the victim. Traumatic incidents can include kidnapping, serious accidents such as car or train wrecks, natural disasters such as floods or earthquakes, or violent attacks such as rape, sexual or physical abuse, or FGC. As defined—although culturally sanctioned— FGC is a traumatic event (see chart from Sahiyo’s study below). Although for some the consequences can be minimal, most of the evidence suggests that FGC is extremely traumatic and the physical or medical complications associated with FGC may remain acute or chronic. Early, life-threatening risks include hemorrhage, shock secondary to blood loss or pain, local infection and failure to heal, septicemia, tetanus, trauma to adjacent structures, and urinary retention. One of the more frequent longer-term medical consequences includes adhesions or scarring, which can contribute to lingering pain and impede sexual functioning. The focus of FGC has long been regarded from a physical and medical perspective but it is equally important to consider the psychological and emotional implications of this practice. It has been reported that the psychological trauma that women experience through FGM ‘often stays with them for the rest of their lives’ (Equality Now and City University London, 2014, p.8). Sahiyo’s study found that of the 309 participants in the study who had undergone FGC in the Dawoodi Bohra community, almost half (48%) reported that the practice left a negative emotional impact on their adult life. Usually, the girl, unprepared for what is about to happen, is taken by surprise and cannot prevent what is about to occur. Those that can remember the ‘day they were cut’ often report having initially felt intense fear, confusion, helplessness, pain, horror, terror, humiliation, and betrayal. Many have suffered a multi-phase trauma; the first being forced down and cut and then second is seeing or hearing another family member endure the procedure. Even anticipating the procedure, oneself can be terrifying. Also of significance is the community and family reaction to the painful reactions experienced by these young women. Often girls can be chided for crying and not being brave while undergoing the cutting. This dismissive, non-nurturing reaction can potentially lead to another facet of the multi-phase trauma. Some proponents of FGC actually consider that the shock and trauma of the surgery may contribute to the behavior described as calmer and docile—considered to be positive feminine traits. FGC is a traumatic event that can profoundly rupture an individual’s sense of self, safety, ability to trust and feel connected to others—aspects of life considered fundamental to well-being. Such genital violence can interrupt the process of developing positive self-esteem. And, when children are violated their boundaries are ruptured leading to feelings of powerlessness and loss of control. Children who have experienced trauma often have difficulty identifying, expressing and managing emotions, and may have limited language for describing their feelings and as a result, they may experience significant depression, anxiety or anger. Over time, if the distress can be communicated to people who care about the traumatized individual and these caretakers respond adequately, most people can recover from the traumatic event. But, some FGC affected girls and women experience severe distress for months or even years later. The symptoms of trauma: Outlined below are some of the consequences that may occur following a traumatic event. Sometimes these responses can be delayed, for months or even years after the event. Often, people do not even initially associate their symptoms with the precipitating trauma. Physical Eating disturbances (more or less than usual) Sleep disturbances (more or less than usual) Sexual dysfunction Low energy Chronic, unexplained pain Emotional/behavioral Depression, spontaneous crying, despair, and hopelessness Anxiety; feeling out of control Panic attacks Fearfulness Feelings of ineffectiveness, shame, despair, hopelessness Irritability, anger, and resentment Emotional numbness Withdrawal from normal routine and relationships Feeling frequently threatened Feeling damaged Self-destructive and impulsive behaviors Sexual problems Cognitive Memory lapses, especially about the trauma Difficulty making decisions Loss of previously sustained beliefs Decreased ability to concentrate Feeling distracted Over time, even without professional treatment, traumatic symptoms generally subside, and normal daily functioning gradually returns. However, even after time has passed, sometimes the symptoms don’t go away. Or they may appear to be gone, but surface again in another stressful situation. When a person’s daily life functioning or life choices continue to be affected, a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be the problem, requiring professional assistance. To learn more about PTSD, see our Part II – Post Traumatic Stress Disorder About the Author: Joanna Vergoth is a psychotherapist in private practice specializing in trauma. Throughout the past 15 years she has become a committed activist in the cause of FGC, first as Coordinator of the Midwest Network on Female Genital Cutting, and most recently with the creation of forma, a charity organization dedicated to providing comprehensive, culturally-sensitive clinical services to women affected by FGC, and also offering psychoeducational outreach, advocacy and awareness training to hospitals, social service agencies, universities and the community at large.