Learning new methods of data analysis to conduct research on female genital cutting

Photo Courtesy Of Pixabay on Pexels.com By Cameron Adelman A major finding of the research project I have been conducting on the social and emotional correlates of female genital cutting (FGC) is that in communities that are more supportive of FGC, there are more reasons to support the practice. Some reasons in support of FGC include the practice as a coming of age ceremony, being promoted by religious/spiritual/community leaders, and being used to preserve a girl’s virginity and to promote her marriageability. Additionally, women are more likely to suffer social and emotional consequences such as having less social support and more negative feelings surrounding the community’s beliefs. In my last blog post, I talked about the conception of my research project on risk factors for female genital cutting and social/emotional issues related to the practice, and the divergence of the project from what I had originally envisioned. The majority of my data and the statistical analyses I ran were from the Demographic Health Surveys Program (DHS). The analysis of the DHS data pointed toward a number of social, emotional, and physical issues that appeared to be more common in women who had experienced FGC, as well as a number of beliefs that were more common in women who had experienced FGC, and some socioeconomic factors that appeared to be related. From this information, I was able to go through my own data and select the information that could help support a working theory of increased stress and emotional concerns for women who had experienced FGC. My data was also helpful for establishing a link between community attitudes and social/emotional wellbeing. My analysis of the data Sahiyo led to a few key findings: First, the number of cultural reasons supporting FGC was positively correlated with how supportive a community is of FGC. With a positive correlation, this means that as one factor increases, the other does as well, so the more reasons a participant selected for why FGC was a part of her culture, the more supportive her community was likely to be of FGC. Second, the number of cultural reasons for why FGC is practiced was negatively correlated with how the community attitude toward FGC made a participant feel. With a negative correlation, this means that as one factor increases, the other decreases. The more reasons a participant selected for why FGC was a part of her culture, the more negatively she felt about her community’s supportiveness of FGC. Third, how supportive a community is of FGC was negatively correlated with how a participant felt about the community attitude, and how many personal sources of support a participant listed that she had available to her. Finally, the number of personal sources of support a participant had was positively correlated with how a participant felt about her community’s attitude toward FGC. Despite the immense help of Sahiyo, I had only 11 participants of my own after sending out a survey to gather data, which was insufficient for a full research paper. This limit is what led me to the DHS. After seeing how significant the findings from the DHS data were it became clear that the best route forward was to take the aspects of my data from Sahiyo members about community attitudes and use that to supplement my findings from DHS. With my data analysis completed, I’ve begun the work of writing the paper that will hopefully be submitted for publication in a research journal at the end of the semester. The results so far suggest unique challenges to supporting women in communities that still actively promote and support FGC. I hope with the work I have done that it can lead to improved services for women in areas both supportive and unsupportive of female genital cutting. More on Cameron: Cameron Adelman is a senior neuroscience major and women and gender studies minor at Wheaton College in Massachusetts. He has been working on his research project about social and emotional effects of FGC since last year. The findings of his research among women who have experienced FGC suggest a number of sociocultural confounds in trying to develop and deliver support systems for women living in practicing communities. Cameron’s hope is to help advise best practices that take these factors, as well as additional risks to wellbeing, into account.

Moving Beyond Cultural Relativism to a Call for Action to End Female Genital Cutting

By Brionna Wiggins Earlier this year I had no idea about female genital cutting (FGC). None whatsoever. I mean, events happen all the time around the world and I’m not aware of the dozens of happenings that occur day-to-day. But for FGC to go on without so much as a whisper of this harmful practice, I thought was rather strange. I learned about FGC when I was given an assignment during my junior year in high school. It was a Pre-Senior Project, which was essentially a practice before our year-long project we had to do for our final year of high school. Ideally, we were to choose a topic that pertained to our passions or a problem related to us on some level. I was at a loss for what to choose. Everyone around me jotted down several potential ideas, but my ideas were comparatively vague. By day two or so, I sat with my teacher to make a final decision. My teacher wrenched out my distaste for injustice and helped me narrow the target of people who undergo it. She typed online in the search bar something along the lines of “issues involving women and children” and there it popped up–female genital cutting. I was appalled when I first learned about it. To reiterate, I had no idea this tradition existed and I wondered how it continued to go on. Why did women and men subject their daughters to this? What was the appeal? I dug deeper, finding out the reasons behind FGC. In some communities, while the intention was to keep daughters clean or marriageable, it was done at the cost of carrying out a potentially traumatic procedure that could leave the woman or girl with a handful of health issues afterward. However, the concept of cultural relativism impeded criticism and questioning, while justifying the tradition. The idea that because one has not lived in a certain community or society, they can’t truly pass judgment on the cultural practices of others. Two people living in two different places across the world from each other naturally grow up with different experiences. Who is to say that another’s culture and traditional practices are objectively wrong? What is considered wrong when it comes to culture? Outsiders may feel as if they do not have a voice in regard to scrutinizing FGC because it’s an issue beyond their homes. Therefore, proponents of FGC claim that the divide or differences between two groups is too great to judge each other. Admittedly, I initially agreed with the notion of cultural relativism. Who was I to criticize people who carry out FGC in their communities when I knew nothing of their lives? Even so, remaining in place and staying quiet, doesn’t sit well with me, especially if I could be a person who brings awareness to FGC being a human rights violation. The excuse of cultural relativism shouldn’t be used when people are being harmed. I continued researching FGC for my project the next school year, my senior year in high school. This time, the project had to be more extensive, including a longer research paper, another presentation, and some sort of final product. This ranges from documentaries to creating design plans. With all this work I was doing, I thought maybe I could make some sort of difference. I needed a mentor for guidance, one who is an expert on the topic. I sent out an email or two before finding Mariya, a co-founder of Sahiyo. The organization specializes in advocacy regarding FGC, even working with affected communities to diminish the practice. By sharing the stories of women involved with FGC, a wider audience becomes aware of the issue with a deeper understanding. With the combined efforts of multiple organizations and people from different walks of life, the perception of practicing communities will change. Then, I believe, FGC will become part of the past. Over the course of my project, I hope to improve my advocacy skills and fully understand the issue that I’ve been invested in for the past couple of months. So far, researching FGC and looking into multiple perspectives has encouraged me to consider my own views on the topic. By the end, I will have figured out my ethical priorities. For the rest of my blog posts, I want to look into a handful of countries where FGC is practiced and talk about the circumstances around them. Until next time! More on Brionna: Brionna is currently a high school senior in the District of Columbia. She likes drawing, helping others, and being able to contribute to great causes.

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 6: Effects of FGM/C on the Lower Urinary Tract System

(This article is Part 6 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Julia Geynisman-Tan, MD Background FGM/C has no known health benefits, but does have many immediate and long-term health risks, such as hemorrhage, local infection, tetanus, sepsis, hematometra, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, obstructed labor, severe obstetric lacerations, fistulas, and even death. While the psychological, sexual, and obstetric consequences of FGM/C are well-documented (refer to prior posts in this series), there are few studies on the urogynecologic complications of FGM/C. Urogynecology is the field of women’s pelvic floor disorders including urinary and fecal incontinence, dysfunctional urination, genital prolapse, pelvic pain, vaginal scarring, pain with intercourse, constipation and pain with defecation and many other conditions that affect the vagina, the bladder and the rectum. Urogynecologists are surgeons who can both medically manage and surgically correct many of these issues. FGM/C and Urinary Tract Symptoms One recent study from Egypt suggested that FGM/C is associated with long-term urinary retention (sensation that your bladder is not emptying all the way), urinary urgency (the need to rush to the bathroom and feeling that you cannot wait when the urge comes on), urinary hesitancy (the feeling that it takes time for the urine stream to start once you are sitting on the toilet) and incontinence (leakage of urine). However, the women enrolled in this study were all presenting for care to a urogynecology clinic and therefore all of them had some urinary complaints so it is difficult to tell from this study what the true prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms are in the overall FGM/C population. Therefore, given the significant number of women with FGM/C in the United States and the paucity of data on the effects of FGM/C on the urinary system, my research team studied this topic ourselves in order to describe the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in women living with FGM/C in the United States. Publication will be available online in December 2018. We enrolled 30 women with an average age of 29 to complete two questionnaires on their bladder symptoms. Women in the study reported being circumcised between age 1 week and 16 years (median = 6 years). 40% reported type I 23% type II 23% type III 13% were unsure Additionally, 50% had had a vaginal delivery; and 33% of these women reported that they tore into their urethra at delivery. Findings: A history of urinary tract infections (UTIs) was common in the cohort: 46% reported having at least one infection since being cut 26% in the last year 10% reported more than 3 UTIs in last year 27% voided ≥ 9 times per day (normal is up to 8 times per day) 60% had to wake up at least twice at night to urinate (once, at most, is normal) Most of the women (73%) reported at least one bothersome urinary symptom, although many were positive for multiple symptoms: urinary hesitancy (40%) strained urine flow (30%) intermittent urine stream (a stream that starts and stops and starts again) (47%) were often reported 53% reported urgency urinary incontinence (leakage of urine when they have a strong urge to go to the bathroom) 43% reported stress urinary incontinence (leakage of urine with coughing, sneezing, laughing or jumping) 63%reported that their urinary symptoms have “moderate” or “quite a bit” of impact on their activities, relationships or feelings What’s the Connection Between FGM/C and Urinary Symptoms? Urinary symptoms like the ones described above can be the result of a number of factors. Risk factors for urinary urgency and frequency, incontinence, and strained urine flow include pregnancy and childbirth, severe perineal tears in labor, obesity, diabetes, smoking, genital prolapse and menopause. However, given the average age of women in our sample and the fact that only half of them had ever had a vaginal birth, the rate of bothersome urinary symptoms are significantly higher than has been previously reported. FGM/C may be a separate risk factor for these symptoms. Interestingly, the prevalence of urinary tract symptoms in our patients closely resembled that of a cohort of healthy young Nigerian women aged 18-30, in which the researchers reported a prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms of 55% with 15% reporting urinary incontinence and 14% reporting voiding symptoms. The authors do not mention the presence of FGM/C in their study population but the published prevalence of FGM/C in Nigeria is 41%, with some communities reporting rates of 76%. Therefore, it is likely that many of the survey respondents had experienced FGM/C, thereby increasing the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in their cohort. In the study of women in Egypt referenced above, those with FGM/C were two to four times more likely to report urinary symptoms compared to women without FGM/C. The connection between FGM/C and urinary symptoms can be understood from the literature on childhood sexual assault and urinary symptoms. Most women who experience FGM/C recall fear, pain, and helplessness. Like sexual assault, FGM/C is known to cause post-traumatic stress disorder, somatization, depression, and anxiety. These psychological effects manifest as somatic symptoms. In studies of children not exposed to sexual abuse, the rates of urinary symptoms range from 2-9%. In comparison, children who have experienced sexual assault have a 13-18% prevalence of enuresis (bedwetting) and 38% prevalence of dysuria (pain with urination). The traumatic imprinting acquired in childhood persists into adult years. In a study of adult women with overactive bladder, 30% had experienced childhood trauma, compared to 6% of controls without an overactive bladder. There is a neurobiological basis for this imprinting. Studies in animal models show that stress and anxiety at a young age has a direct chemical effect on the voiding reflex and can cause an increase in pain receptors in the bladder. Additionally, the impact of sexual trauma on pelvic floor musculature has been well described. Women who

‘Call it by the Name’: A researcher’s dilemma on the FGM-FGC terminology debate

by Debangana Chatterjee Two years back when I ventured into trying to understand a culturally specific embodied practice pertaining to procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia ‘for non-medical reasons’ as a researcher, the biggest challenge for me was to ‘call it by the name’. Disagreements regarding the usage of the term ‘mutilation’ in Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), bearing a negative connotation, have surged. International organisations and agencies commonly term it FGM. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) justifies usage of the term on the basis of its previous reference in 1997 and 2008 by the interagency statements. WHO also acknowledges ‘the importance of using non-judgemental terminology with practising communities’ and some of United Nations agencies prefer adding the word ‘cutting’. Ultimately, both terms underline the violation of women and girls’ rights. ‘Mutilation’ refers to impairing a vital body part by cutting it off with an explicit intent to harm. In this context, a few other terms used to connote FGM require closer attention. Female circumcision and excision are often used identically with FGM, although these do not fully carry the information regarding the practice. Out of the four types of procedures entailing FGM as specified by WHO, female circumcision appears akin to type I and even occasionally type II FGM and appears not as physically severe as the Type III category. Yet, existing research suggests that treating female circumcision as replacements for FGM fails to take the practice into account in its entirety. Using ‘female genital surgeries’ is contested as well, as it appears to validate medicalisation of FGM or in other words implies that FGM is a medical surgery like other standard surgeries. The term FGM received significant prominence in the 1990s. Fran Hosken coined the term in 1993 to draw international attention to the ill-effects associated with the practice as well as to distinguish it from the widely prevailing male circumcision practices. For Ellen Gruenbaum the term ‘…implies intentional harm and is tantamount to an accusation of evil intent’ and thus, entails greater chances of hurting sentiments. There are scholars like Stanlie M. James and Claire C. Robertson who prefer Female Genital Cutting (FGC) instead of FGM. They consider ‘circumcision’ insufficient as it makes a ‘false analogy’ to male circumcision. At the same time, they disagree with the term FGM as it subsumes that all types of the procedure are an act of ‘mutilation’. Anika Rahman and Nahid Toubia also choose the understanding of FGC and circumcision as to not force women to dwell on their body as mutilated. These scholars understand the sense of trauma that ‘mutilation’ might connote for some women. In fact, the constant reference of FGM in the existing international human rights (IHR) discourse mostly remains unaware of other forms of bodily mutilation of women. ‘Mutilation’, in this sense, can mean both bodily modifications attempted through cosmetic surgeries and public sexual violence which remains under the sovereign jurisdiction of the states concerned. Needless to say, mutilation of raped bodies is one of the most common occurrences of sexual violence. When FGM as a cultural practice is emphasised over other forms of ‘mutilation’, it indicates the cultural biases of IHR discourse. It is not to dilute the abhorrence that this practice deserves, but to show how little a space it leaves for consciousness building and community learning. For both the activists and researchers alike, extreme caution is required to not alienate people and to sustain the dialogic engagement with them. Also, with ‘mutilation’, a popular imagery of infibulation (narrowing of the vaginal orifice) is attached. It comes more with its representation in popular culture as is the case with the film Desert Flower. Notwithstanding the reality of the incidence shown in the movie, in most of the cases, the type I and II procedures are conducted instead of type III (infibulation). Clubbing all the procedures under the single rubric either exaggerates type I and II FGM or dilutes the gravity of Type III and some forms of Type IV (Type IV includes miscellaneous procedures like piercing, pricking, incising or stretching of the clitoris, burning or scraping of vaginal tissues. Whereas some of the type IV procedures are of greater concern, others may not necessarily appear as severe). In the light of these debates over terminologies, how does a researcher resolve her dilemma? My study aims to locate the practices of FGM/C exclusive to the Bohra Muslim community in India in the frame of international politics. Especially keeping in mind my position as a scholar who is outside the purview of the culture, I stand on the edge of being either called a cultural relativist/apologist (a person who believes that people’s cultural traditions can only be judged by the standards of their own culture and thus, cultural practices are to be judged relative to the understanding of its practitioners) or prejudiced against cultural particularities. My study aims to juxtapose international discourses surrounding the practice vis-a-vis its occurrences in India. Hence, while writing my thesis, I shall be using FGM interchangeably with FGM/C to reflect the larger WHO definition and its usage in the international circle. As no term seems perfect in defining the practice, academically FGM/C looks commonly acceptable reflecting the international outlook towards it. Needless to say, the term FGM/C also has received substantial backlash from the communities and Bohras are no exception to it. An objective and unbiased study of the practice seeks the right approach more than an elusive perfection in terminology. Thus, during my interactions with members of the community, while analysing the local Indian discourse, khatna as a term will be given preference respecting the cultural uniqueness that the term bears. More about Debangana Debangana is a doctoral scholar at the Centre for International Politics Organisation and Disarmament (CIPOD), Jawaharlal Nehru University. Through her research, she is trying to locate the existing Indian discourse surrounding the practices of FGM/C and Hijab into the frame of international politics. If you would like to connect with Debangana, you can

Feeling drained after talking about Khatna? Here are some resources that can help

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography and writing. She is currently conducting a research on the individual experience of Khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series – Khatna Research in Mumbai. As human beings we are trained to react immediately, lessen the magnitude of pain when injured, manage our emotions when overwhelmed. We always initiate a response, however not all actions can be immediately responded to, especially when they are extremely distressing or traumatic. Often they are hidden away by our minds to prevent any major upheaval for us. However, even when hidden, they tend to seep through the cracks, leading to subtle effects such as difficulty falling asleep, distrustfulness, self doubt, among others. But sometimes, a small object, event or even a word can widen the crack, leading to a dam of emotions running out. This process is called re-traumatization. Perhaps the best description of the same would be an object, event or situation which leads to re-experiencing the emotions and physical symptoms that are associated with the initial episode of trauma. It is essential to acknowledge that all individuals give a similar physical response to trauma, but the psychological response is never the same. For example, we are biologically programmed to give a physical response to pain, such as crying when injured. However, we are culturally conditioned to suppress the psychological pain caused by the injury, which is essentially the case with women who have undergone FGC/Khatna. Although the pain is suppressed, it cannot be avoided because it begins to manifest indirectly. For example, one of the participants, I interviewed for my research reported that although she does not remember anything from the day of her Khatna, she has been terrified of blades ever since then. This is a clear example of unaddressed psychological distress. Thus, irrespective of whether the response to trauma is immediate, delayed, drastic or subtle, all individuals must gain access to resources for assistance. Therefore, while delving into a topic such as Khatna, which is emotionally charged and traumatic, it is the researcher’s responsibility to ensure that the effect of re-traumatization is minimized. As cliché as it sounds, listening is perhaps the best therapeutic tool to minimize re-traumatization. Case studies have shown that when victims of trauma are unheard they are more likely to indulge in self-destructive behaviour. Besides listening, providing an open and safe environment, choices, lists of resources and being available post the interview are also known to help. However, it is essential that a sense of independence be encouraged. Therefore survivors must be trained to look out for signs on their own and have a some set of immediate resources be available for themselves. Some of the signs to look out for: Sudden and recurring thoughts of an unpleasant event, that may be difficult to control. Change in sleeping habits: an increase or decrease in the need for sleep, as compared to before the interview with the researcher. Change in eating habits: an increase or decrease in appetite as compared to before the interview with the researcher. Difficulty paying attention to an activity at hand, inability to remember information. Easily irritated. Not interested in participating in activities which were earlier enjoyable. Frequent crying spells. Using negative statements (“I am bad”) while addressing oneself. Having extremely negative view of the world (“everyone in the world is bad”). Regular thoughts of death or harming oneself. Distrust and suspiciousness of those around oneself. Sense of powerlessness Increased feeling of fear Things to do: Seek out a trusted confidante and talk to them, it will allow you an emotional release as well as provide the support to overcome the current distress you feel. Arrange your day in a way that allows for at least 1 or 2 activities, such as painting or dancing among others, which give you positive emotions such as happiness. These activities could last from anywhere between 30 minutes to an hour, preferably not consecutively organised. Seek out support in organizations – research has shown that women who choose to speak out about their trauma by joining organizations working against the trauma that they survived are more adept with dealing with their emotions as they are able to gather wider support of individuals with similar experiences. Perform physical activity which would allow your body to release positive hormones which would assist in overcoming some of the negative emotions you may currently feel. Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Progressive muscle relaxation is a two-step process in which you systematically tense and relax different muscle groups in the body. With regular practice, it gives you an intimate familiarity with what tension—as well as complete relaxation—feels like in different parts of the body. This can help you to you react to the first signs of the muscular tension that accompanies stress. And as your body relaxes, so will your mind. Steps involved: Start at your feet and work your way up to your face, trying to only tense those muscles intended. Loosen clothing, take off your shoes, and get comfortable. Take a few minutes to breathe in and out in slow, deep breaths. When you’re ready, shift your attention to your right foot. Take a moment to focus on the way it feels. Slowly tense the muscles in your right foot, squeezing as tightly as you can. Hold for a count of 10. Relax your foot. Focus on the tension flowing away and how your foot feels as it becomes limp and loose. Stay in this relaxed state for a moment, breathing deeply and slowly. Shift your attention to your left foot. Follow the same sequence of muscle tension and release. Move slowly up through your body, contracting and relaxing the different muscle groups. It may take some practice at first, but try not to tense muscles other than those intended. 6. Mindfulness Meditation: Rather than worrying about the future or dwelling on

Asking more questions is the key to change, and to ending Female Genital Cutting

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography and writing. She is currently conducting a research on the individual experience of Khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series – Khatna Research in Mumbai Flexibility is a key characteristic of successful research, and it is an extremely essential component of the questions on which the research is based. Although I believe that having an exhaustive list of questions pre-prepared is essential to keep one on track, however as one reads and interacts with others, newer lines of enquiry are generated. It is crucial that all lines of enquiry be amalgamated to allow for a wholesome insight into one individual’s experience. Currently my interactions with women allowed me to see connections in their narratives. Accompanied by the literature I read, I found similarities as well as differences in the narratives of women across the world. Researchers have found that Female Genital Cutting (Khatna) leads to urinary problems, menstrual problems, problems in sexual functioning and difficulties during childbirth; some have even found that the psychological distress of the trauma often leads to depression and anxiety among women. A common pattern I found among studies was that all mental distress experienced by women was studied as a didactic relationship, ie, the women in relation to another individual. For example, sexual difficulties leading to marital distress among husband and wife. However it was intriguing that in my interactions with women I found that Khatna has a great impact on the women’s relationship with themselves. For example, a participant reported that she dealt with self-esteem issues because she felt out of place while growing up, as she did not have the same sexual impulses towards boys as her other friends, the lack of which she attributed to Khatna. My area of interest was always the psycho-social effect of Khatna. However, now I am more curious than ever to explore how Khatna impacts both women’s social relationships as well as their relationship with themselves. Little research has been done to explore how an individual’s worldview (ie, understanding of the world and how it functions) shifts after their discovery and understanding of Khatna. My curiosity in this area was ignited when one woman reported that following her discovery of Khatna, she was extremely angry with her family and although she has now made peace with her family, her trust in them and her faith in people’s ability to make good decisions has been shattered. I am now fascinated to interview more women and see how their worldview might have shifted after their discovery of Khatna. Furthermore, research in attitude formation shows that negative experiences with one aspect of a larger domain leads to a negative attitude towards all aspects of the domain. If the same was extended to the practice of Khatna rooted in religious obligation, it would be interesting to explore how attitudes towards Khatna and religion are interlinked. With each conversation, the questions in my mind multiply and it is often followed by a sense of hesitation of being overambitious. However, I do not let the hesitation pull me back, and the credit for that goes to one research participant who told me that if someone before us had asked these questions, then we wouldn’t have to be here today, and unless we ask these questions, nothing will change and we will still be here five years down the line. I have made a decision to change, have you? To participate in Priya’s research, contact her on priya.tiss.2018@gmail.com

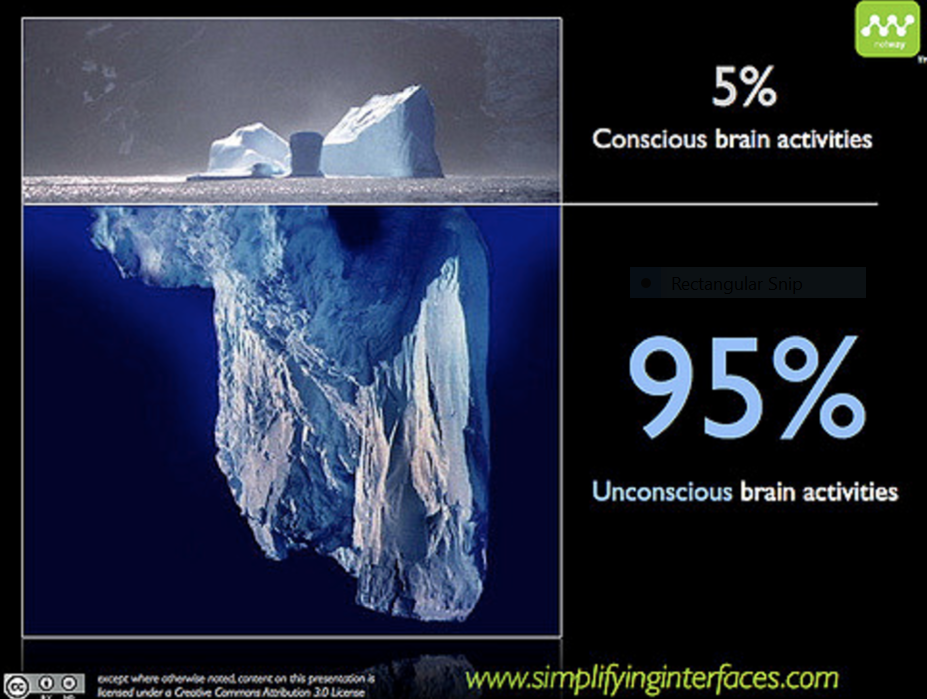

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 3: The Body and the Brain

(This article is Part 3 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Trauma overwhelms us and disrupts our normal functioning, impacting both the brain and body, both of which interact with one another to regulate our biological states of arousal. When traumatized, we lose access to our social communication skills and displace our ability to relate/connect/interact with three basic defensive reactions: namely, we react by fighting, fleeing, or freezing (this numbing response happens when death feels imminent or escape seems impossible). In order to understand and appreciate our survival responses, it’s important to have a basic understanding of how our brain functions during a traumatic experience, such as undergoing Female Genital Cutting or FGC. Our brains are structured into three main parts: The human brain, which focused on survival in its primitive stages, has evolved over the millennia to develop three main parts, which all continue to function today. The earliest brain to develop was the reptilian brain, responsible for survival instincts. This was followed by the mammalian brain (Limbic system), with instincts for feelings and memory. The Cortex, the thinking part of our brain, was the final addition. The Reptilian brain: The reptilian brain, which includes the brain stem, is concerned with physical survival and maintenance of the body. It controls our movement and automatic functions, breathing, heart rate, circulation, hunger, reproduction and social dominance— “Will it eat me or can I eat it?” In addition to real threats, stress can also result from the fact that this ancient brain cannot differentiate between reality and imagination. Reactions of the reptilian brain are largely unconscious, automatic, and highly resistant to change. Can you remember waking up from a nightmare, sweating and fearful—this is an example of the body reacting to an imagined threat as if it were a real one. The Limbic System: Also referred to as the mammalian brain, this is the second brain that evolved and is the center for emotional responsiveness, memory formation and integration, and the mechanisms to keep ourselves safe (flight, fight or freeze). It is also involved with controlling hormones and temperature. Like the reptilian brain, it operates primarily on a subconscious level and without a sense of time. The basic structures of Limbic system include: thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus The Neocortex: The neocortex is that part of the cerebral cortex that is the modern, most newly (“neo”) evolved part. It enables executive decision-making, thinking, planning, speech and writing and is responsible for voluntary movement. But… Almost all of the brain’s work activity is conducted at the unconscious level, completely without our knowledge. While we like to think that we are thinking, functioning people, making logical choices, in fact our neocortex is only responsible for 5-15 % of our choices. When the processing is done and there is a decision to make or a physical act to perform, that very small job is executed by the conscious mind. How the brain responds to Trauma The fight or flight response system — also known as the acute stress response — is an automatic reaction to something frightening, either physically or mentally. This response is facilitated by the two branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) which work in harmony with each other, connecting the brain with various organs and muscle groups, in order to coordinate the response. Following the perception of threat, received from the thalamus, the amygdala immediately responds to the signal of danger and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated by the release of stress hormones that prepare the body to fight or escape. It is the SNS which tells the heart to beat faster, the muscles to tense, the eyes to dilate and the mucous membranes to dry up—all so you can fight harder, run faster, see better and breathe easier under stressful circumstances. As we prepare to fight for our lives, depending on our nature and the situation we are in, we may have an overwhelming need to “get out of here” or become very angry and aggressive (See ‘I underwent female genital cutting in a hospital in Rajasthan’ on Sahiyo’s blog). Usually, the effects of these hormones wear off only minutes after the threat is withdrawn or successfully dealt with. However, when we’re terrified and feel like there is no chance for our survival or escape, the “freeze” response, activated via the parasympathetic nervous system, can occur. The same hormones or naturally occurring pain killers that the body produces to help it relax (endorphins are the ‘feel good’ hormones) are also released into the bloodstream, in enormous amounts, when the freeze response is triggered. This can happen to people in car accidents, to sexual assault survivors and to people who are robbed at gunpoint. Sometimes these individuals pass out, or mentally remove themselves from their bodies and don’t feel the pain of the attack, and sometimes have no conscious or explicit memory of the incident afterwards. Many survivors of female genital cutting have reported fainting after being cut. Other survivors have reported blocking out their experiences of being cut (See ‘I don’t remember my khatna. But it feels like a violation’). Our bodies can also hold on to these past traumas which may be reflected not only in our body language and posture but can be the source of vague somatic complaints (headaches, back pain, abdominal discomfort, etc.) that have no organic source. FGC survivors who were cut at very young ages can be plagued with ambiguous symptoms such as these. Neuroscientists have identified two different types of memory: explicit and implicit. The hippocampus, the seat of explicit memory, is not developed until 18 months. However, the implicit memory system, involving limbic processes, is available from birth. Many of our emotional memories are laid

A conversation with change makers: women who chose to speak up about Khatna

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography and writing. She is currently conducting a research on the individual experience of Khatna and its effects. To read Priya’s first blog in this series, visit ‘How I found out Khatna exists and why I choose to speak out’. The first time I heard the statement,“Well it could have been you! It could have been anyone! But it happened to me,” by a woman who had gone through khatna, I felt its weight immensely on me. I do not yet have the answers for why this statement affected me so intensely, but it has strengthened my resolve to understand and generate more awareness about Khatna, because it has affected women for so long and has the capacity to affect many more. The first step in my research journey is to talk to women who have been directly affected by Khatna. While deciding upon the questions to ask my participants, my number one concern was to not sound insensitive or biased when asking them about Khatna. More importantly, I wondered how to ask questions about something this personal without sounding intrusive. The sensitivity of the questions depends on the context in which you ask the question rather than how you frame it, whereas the intrusiveness of it depends on the reactions from the women. It was interesting for me to observe that none of the women found the questions to be intrusive or uncomfortable, rather there was a normalized, patterned response given from them, as if these were routine questions. My early hypothesis was that women would feel overwhelmed while responding to these questions, but that is not what I found. There are two possible reasons for this: one, they have been asked these questions before and thus have already reflected on the questions and know the answers for themselves; two, by choosing to speak about Khatna, they have already begun their healing process and by normalizing speaking about the incident they perhaps have taken back a sense of control that they had lost when they underwent it. Future interactions with more women will allow me to formulate a definite conclusion. It was fascinating to observe that although each woman had an individual experience of Khatna, their stories were eerily similar and the trajectory of growing up and figuring out the significance of it was uncannily alike. A lot of the women I interviewed had repressed their memory of the day of their Khatna, and they grew up without any conscious knowledge of what had happened or what it meant, only to discover its significance much later in life. However, perhaps their discovery of Khatna later in life comes due to the ripple effect created by one woman speaking out. The women I have spoken with have talked about how hearing how other women were speaking about their experiences helped them to remember their own experience of Khatna. While interviewing women, some common traits I found among the respondents were curiosity, a fierce need for answers and an extraordinary amount of courage. All the women I interviewed had an aura of strength around them which was empowering. It crushed the fear and hesitancy I had in asking the questions, and it empowered me to not only raise more questions about Khatna. Through reflection, I found that change happens through empowering conversations. While doing this research, always at the back of my mind, has been the questions of “Who are the changemakers?” I recognized that change-makers are those who have the courage to question the law of the land, who show resilience in the face of daunting challenges and who empower others to fuel the fire of change. These women have empowered me to continue the change, and I request you to join me in further promoting this change. If we do not speak out, then who will? To participate in Priya’s research, contact her on priya.tiss.2018@gmail.com

Why the new survey on Khafz (Female Genital Cutting) among Bohras is biased and unscientific

By Mariya Taher, MSW, MFA Last week, many Dawoodi Bohras around the world received the link to an online “research” survey with questions about Khatna/Khafz practiced in the community. Khafz refers to cutting a portion of a girl’s clitoral hood – a type of Female Genital Cutting – and this new online survey by Dr. Tasneem Saify, Dr. Munira Radhanpurwala T and Dr. Rakhee K claims that it aims to get feedback from Dawoodi Bohra women and men about the practice. (Link to survey is here). As someone who has gone through the process of designing multiple research studies, I can confidently say that this latest survey on Khatna/Khafz in the Bohra community is neither a safe nor an unbiased tool for conducting proper research on female genital cutting. Other academic researchers who reviewed the Khafz survey have also pointed this out. For example, Usha Tummala-Narra, Ph.D., an associate Professor in the Department of Counseling, Developmental and Educational Psychology at Boston College, states: “The questions are strangely worded, and implicitly and explicitly suggest that the practice is not mutilation or traumatic. There are also no questions related to girls’ or women’s experiences of the practice. We can’t really know much about the definition of khatna/khafz without asking about the experience and its effects over time.” While Karen A. McDonnell, an Associate Professor and Vice-Chair in the Department of Prevention and Community Health at Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University, states: “Overall this survey presents itself as a feedback mechanism from Dawoodi Bohras about female circumcision. Taking the perspective of someone trained in objective survey development in psychology and public health, the survey actually reads in its entirety, not as a feedback, but rather as a tool for marketing a perspective. As the survey proceeds, the tenor of the questions increase in a lack of objectivity and a central cause/message is quite clear and the respondent is made to feel manipulated.” While all research has its limitations, the design of this questionnaire suggests that it clearly was NOT created and sent out into the world to collect empirical unbiased research on the practice FGC/Khatna/Khafz. Instead, the bias and manner of wording of this survey tool express that the authors (Dr. Tasneem Saify, Dr. Munira Radhanpurwala T & Dr. Rakhee K) are seeking responses that will justify their motives to prove that Female Genital Cutting (FGC) does not harm girls. Which makes me wonder, was this research tool (the survey) even vetted before the study’s implementation? In 2008, because of my increasing passion to end violence against women, I choose to craft and carry out research for my Master of Social Work thesis on “Understanding the Continuation of Female Genital Cutting Amongst the Dawoodi Bohras in the United States.” The issue had been in the recesses of my mind for years and I wanted to learn how a practice that involves cutting the sexual organs of a young girl could ever have been deemed a religious or cultural practice. I wanted to understand how the issue of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) could continue generation after generation without question, because if I could understand this reasoning, then I could better understand why FGC had been done to me at the age of seven. As a graduate student, my thesis advisors walked me through every step of the research process, from consulting references and existing studies, to contacting other academics and experts who had studied FGC. In the end, I carried out an exploratory study and crafted questions that could be used to conduct ethnographic interviews. Ethnographic interviewing is a type of qualitative research that combines immersive observation and directed one-on-one interviews. In order to draft the questions, I consulted questions used in previous studies by other researchers. My thesis advisors reviewed the questions, and the San Francisco State University’s Institutional Review Board examined my question to ensure there was no hidden bias in the wording of my questions that could lead participants to answer one way or the other. Having been through the process once, and understanding the importance of having multiple individuals review your questions for hidden biases, years later, I went through a similar process when Sahiyo designed its study on Khatna among Dawoodi Bohra women. Prior to engaging Bohra women for the study, our research tool (the survey) was vetted by many NGOs and expert researchers. If this newest Khafz questionnaire by Dr. Tasneem Saify, Dr. Munira Radhanpurwala T & Dr. Rakhee K had been vetted by other individuals and institutions, it would have recognized the following problems well before releasing the study to the public. 1) Participant consent Prior to filling out a study, it is important that participants are informed of the study’s intention and are able to sign a consent form acknowledging that they understand the study’s purpose and are giving their permission for the findings to be used in a study’s report. The new Khafz -survey does not have a consent form that does such. [See Screenshot to the left]. In fact, the purpose of this survey is misleading to the reader. There is no mention of how the respondents are being recruited and if their responses will be anonymous or even held in confidence and in essence violates a respondents rights as a participant. 2) Confidentiality The new Khafz survey form requires participants to provide information that will NOT allow their information to remain private. The study requires that participants add their Community ID (ITS52/Ejamaat) Number. As reported in Mumbai Mirror, the ITS number keeps track of a Dawoodi Bohra’s personal details, including the number of times a person visits the mosque. By requiring an individual to enter this information, already the researchers have directly violated a person’s right to privacy. The question also limits respondents to only those who have signed up for such an ITS number. This, therefore, rules out the participation of many individuals born into the Bohra community or to a Bohra parent who may not have signed up

We did a project on FGC in college and learned our Bohra Classmates had undergone it too

By Rachael Alphonso, Green Madcaps City: Mumbai, India I’m no fan of Vogue, so I was wondering what the face of a pretty African model, Waris Dirie, was doing on the cover of my favourite Reader’s Digest. ‘Desert Flower’, the title said. Her photo betrayed no sign of what she had suffered in her childhood – Female Circumcision or Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). ‘Circumcision’ – wasn’t it something only men had to undergo? How was it physically possible for women? And why? Having read the Bible and references to the Torah, I had never found any reference to women needing circumcision. So what was this all about? I read the article, “….a sharp stone…I felt the sting…my flesh was being torn away…no anaesthetic….” I couldn’t imagine the pain! Had it not been the Reader’s Digest, I would not have believed it! Because of her ‘circumcision’, menstruation for Waris was utterly painful. She could not have a steady flow which resulted in painful cramps. Soon, she was married to a man a few decades her senior who would have to tear open the skin over his wife’s vagina to be able to penetrate her during sex. Childbirth would be worse. I was stunned reading about it, and when my group in college was asked to do a project I was quick to gain support from my group to investigate this topic. We began our research. Our discussions and debates within the group, despite all efforts, became one-sided simply because we believed that nothing ever could justify the genital mutilation that Waris or any other girl suffered as a result of the circumcision. We could not find any medical or rational evidence that supported the idea. But the perpetrators of FGM continued to say it was done for the ‘benefit’ of the women and that women’s sexuality needed to be tamed. Men ‘simply fell for it’ [sex], and men could not control themselves, so women had to be controlled. We found this argument had taken different forms in different cultures, emerging into practices that control women and make them believe they are nothing more than their sexual organs, nothing more than a womb that bears children. We presented this topic to the rest of our class, and were proud of ourselves for doing so. Unconsciously, we also believed we were less affected by FGM because we also believed FGM could not happen in India. We were wrong. After our presentation we learned that many of our classmates were victims of ‘khatna’– a practice by which a piece of the clitoral hood is removed. Our classmate told us that the reason given by her religious leaders was that if a woman found pleasure in her sexual organs she would go on a rampant sexual orgy with anybody. Her sexual urges needed to be controlled so her morality was ensured. Their justification for khatna was also aligned with their belief that because men cannot control their sexual urges, women must remain covered and ‘decently’ dressed. The classmate who spoke of her own khatna and her cousin’s ‘khatna’ revealed that when they experience sex, they most likely would not be able to experience the clitoral orgasmand/or sex would seem slightly sensitive, but that’s all in terms of ill effects. She also informed us that nowadays, painkillers are used, and the procedure is done by a qualified medical professional. My group realized that she was made to believe that khatna was good for her, the harm nonexistent, as long as the cutting was done using the correct instruments and anesthetics.Later, we realized that many women may be traumatized by their experience but they are unable to speak about it, because they may not recognize they have a right to do so While Nigeria banned FGM in early 2016 – something that my presentation group and I heralded as a great move – we also learned that the Bohra leaders in India announced ‘khatna’ as a necessary part of their religion. The leaders claim it was meant for cleanliness, but to me, it is clear that the clitoris is in no need of surgical manipulation for cleanliness. What I find most interesting is that these ‘rules’ and ‘announcements’ were made by men (as the Bohra religious authorities are all men) who themselves do not possess a vagina and know little about the care of one. Millions of women have survived without undergoing khatna. My friends and I are among them. Then why are my Bohra sisters forced to believe otherwise? Who made these rules? Does the rule-maker have a vagina? (The original article appears on Green Madcap’s blog.) Rachael Alphonso is a life-long learner, a feminist and an environmentalist.