How I found out Khatna exists and why I choose to speak out

By Priya Ahluwalia Snugly sitting on my bed on the wintry night of December, a cold chill ran down my spine as I read through the Change.Org petition against Female Genital Mutilation also known as Female Genital Cutting or Khafz. I failed to recognize the magnitude of this practice because of the lack of knowledge of my own genitalia, but reading the petition created dread in my mind. The dread transformed into anger, anger towards the society that violated its own daughters, anger towards all those who let the practice continue and anger towards the ignorance of my own immunity. In anger I signed the petition but it was the vicarious traumatisation I went through while reading the petition in the first place that made me speak out. An implicit responsibility of those choosing to speak out is to create more awareness. However, to my amazement I found that despite the multitudes of women affected by it, the information on FGC was little. Therefore I never understood the true roots of the practice and its implications on the community until this February at Sahiyo’s activists retreat in Mumbai. The retreat was perhaps the most comprehensive and genuine source of information about the Bohra community, the practice of Khafz and its implications. The retreat was also responsible for breaking one of the biggest barriers I had while talking about this practice: intellectualization. I had honed the tendency to talk about FGC mechanically, removing all speck of emotion from my voice as a way of protecting myself from further distress and also to prevent any secondary opinions or personal bias colouring my narrative. However emotions are fundamental to those who choose to speak out including myself, and therefore ignoring them would be a grave injustice to us all. A one-toned discussion has never led to any change, therefore it is integral that while holding a discourse on Khatna, the emotions be incorporated within the facts. While presenting FGC as a topic in my school and college years, I often noticed the discomfort that many people feel as soon as the term genitalia was introduced. I couldn’t help but wonder that if verbalizing the word caused so much distress to an adult, then imagine the fear felt by the seven-year-old girl whose legs were held apart and her rights stolen away. I can feel the anguish, I can feel the anger and I can feel the betrayal she must have felt, because I could have easily been that girl, but here is where my immunity lies; I come from a community where this form of gender violence does not exist. However, the immune must support raising those who have undergone FGC which is why I chose this as a topic for my master’s thesis. This was not a decision I took lightly or quickly, because I know the responsibility that lies with me. I had felt reluctance because I wondered if I, an outsider with little understanding of the community and the practice, would be able to do justice to the women and their stories. I do not know how the thesis will turn out but I know that I will do my best to do right by the women who choose to speak to me. They will not be just data but people with stories to tell that need to be protected and preserved. My aim is to understand the practice as a whole and therefore, I do not want to have a hypothesis of the results I will get, rather I wish to incorporate in my research as many voices as I can, both those who are pro-khatna and those who oppose it. My job as a researcher will be to be open to all narratives and record them as authentically as I can. All of us have a voice and therefore have the responsibility to use it wisely. Thus, I choose to use my voice for myself and all those women who have been silenced under the burden of tradition. (Priya Ahluwalia is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography and writing. To participate in her research, contact her on priya.tiss.2018@gmail.com )

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 2: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

(This article is Part 2 of a seven-part series on trauma related to FGC. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Post-Traumatic Stress is the name given to a set of symptoms that persist following a traumatic incident and may be especially severe or long when the stressor has been of human design, such as in a violent personal/sexual assault (as in rape, torture, or Female Genital Cutting). These symptoms, which recreate the physical reliving of the trauma, can affect the way we think, feel and behave and, if experienced frequently, the condition that develops is called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a complex psycho-biological condition that develops differently from person to person because everyone’s nervous system and tolerance for stress is a little different. While you’re most likely to develop symptoms in the hours or days following a traumatic event, it can sometimes take weeks, months, or even years before they appear. The specific symptoms of PTSD can vary widely between individuals, but generally fall into the categories described below . Re-experiencing Re-experiencing is the most typical symptom of PTSD and occurs when a person involuntarily and vividly re-lives the traumatic event in the form of a flashback. Flashbacks appear as memories or fragments of memories from recent or past events and can leave you feeling fearful, confused and distressed. Jarring and disruptive, they can last a few brief seconds or involve extensive memory recall. Below are the categories and some examples of flashbacks: Visual Memories: various related images Auditory Memories: sounds of breathing, doors shutting, footsteps. Emotional Memories: feelings of distress, hopelessness, rage, terror or a complete lack of feelings (numbness). Body Memories: physical sensations like genital pain, nausea, gagging sensation, difficulty swallowing, feeling of being held down. Sensory Memories: of certain odors (e.g. perfume, body odor, alcohol) or tastes (e.g. sweat, blood). For some women affected by Female Genital Cutting (FGC), re-traumatizing triggers can be their initial (and ongoing) sexual experiences. Not only can the physical position (identical to that required for FGC) induce a flashback, but the already traumatized genital area can feel repeatedly violated with sexual activity, gynaecological exams or childbirth itself. Flashbacks can be accompanied by the same physiological reactions experienced at the time of the trauma, such as dizziness, rapid heartbeat, or sweating. In response to these distressing memories people can develop breathing difficulties, experience disorientation, muscle tension, pounding heart, shaking. Hyperarousal Trauma is stress run amuck. It dis-regulates our nervous systems and distorts our social awareness—displacing social engagement with defensive reactions. This state of mind is known as hyperarousal and often leads to: Irritability; angry outbursts sleeping problems; nightmares difficulty concentrating In severe cases, many have trouble working or socializing and may engage in reckless behaviors (driving too fast; being argumentative or provocative). Others with PTSD may feel chronically anxious and find it difficult to relax or concentrate. Also, problematic for many is difficulty falling or staying asleep or suffering from nightmares; feeling always anxious and on edge (referred to as hypervigilant) –they may easily be startled. Feeling afraid is a common symptom of PTSD and having intense fear that comes on suddenly could mean you are having a panic attack. It can happen when something reminds you of your trauma, and may trigger fearing for your life or losing control. Although anxiety is often accompanied by physical symptoms, such as a racing heart or knots in your stomach, what differentiates a panic attack from other anxiety symptoms is the intensity and duration of the symptoms. Panic attacks typically reach their peak level of intensity in 10 minutes or less and then begin to subside. Negative emotional states Some FGC-affected women may feel betrayed and develop problematic relationships with their mother, or female authority figures, and suffer from low self-esteem and concerns about body image. In addition, traumatized girls and women may develop persistent negative emotional states (e.g. fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame) and engage in distorted thinking such as “I am bad,” “No one can be trusted,” “The world is completely dangerous place.” In Sahiyo’s online survey of Dawoodi Bohra women, conducted in 2015-16, 48% of the women who had undergone FGC reported that the experience of FGC (khatna) left an emotional impact on their adult life. This impact included feelings of being haunted/traumatized by the memory of being cut, feeling betrayed and violated by the family, feelings of distrust towards them, as well as anger and fear. Avoidance and emotional numbing Trying to avoid being reminded of the traumatic event is another key symptom of PTSD. Individuals may try to block out the anxiety or fear associated with the distressing emotional feelings, by avoiding places, people and situations reminding them of the original traumatic experience. For example, the possibility of seeing the “cutter” in a social gathering may be very distressing and re trigger re-traumatization. (See A Pinch of Skin documentary by Priya Goswami). Some people attempt to deal with their feelings by trying not to feel anything at all. This is known as emotional numbing. Many people with PTSD try to push memories of the event out of their mind, often distracting themselves with work or hobbies. Others may engage in self-destructive behaviors (drug or alcohol abuse; eating disorders) in order to distract or numb themselves to feelings that are too painful to tolerate. Those feeling detached and numb often have trouble showing or accepting affection and, becoming isolated and withdrawn, may lose interest in people or activities they used to enjoy. Dissociation is a mental process that causes a lack of connection in a person’s thoughts, memory and sense of identity. It is a normal reaction to trauma and can help cut off the pain, horror and terror for a person experiencing mortal danger; an attempt to be “outside” the events (outside of oneself; besides oneself) happening rather than “inside”

Building the data on Female Genital Cutting in the Bohra Community

In February 2017, Sahiyo released the findings of the first ever large scale global study on Female Genital Cutting in the Bohra community in order to gain insight into how and why this harmful practice continued. A year later, this February 2018 saw the release of a second large-scale research study entitled “The Clitoral Hood – A Contested Site”, conducted by Lakshmi Anantnarayan, Shabana Diler and Natasha Menon in collaboration with WeSpeakOut and Nari Samata Manch. The study explored the practice of FGM/C in the Bohra community specifically in India and added findings about the sexual impact of FGC on Bohra women. Substantial overlap between the two studies can be found and parallels can be drawn. Firstly, both studies explored the type of FGM/C that was carried out on the participants. The study by Sahiyo discovered that out of the 109 participants who were aware of the procedure that was carried out on them, 23 reported having undergone Type 1a – the removal of the clitoral hood. Research carried out by Anantnarayan et. al. found that although proponents of FGM/C in India claim that Bohras only practice Type 1a and Type 4 FGM/C (pricking, piercing or cauterization of the clitoral hood), participants reported that both Types 1a and 1b (partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or clitoral hood) are most often practiced. Sahiyo and Anantnarayan et. al. both found that the majority of participants had undergone FGM/C and therefore, among both samples, FGM/C was widely practiced. Sahiyo found that 80% of 385 female participants had undergone the practice, whereas Anantnarayan et. al. found that of the 83 female participants in the study, 75% reported that their daughters had undergone FGC. Both studies found that FGM/C was performed at around the age of seven. The impact of FGM/C on participants was also reported to be similar among participants of both studies. In exploring this further, Anantnarayan et. al. found that 97% of participants remembered FGM/C as a painful experience. Participants who had undergone the practice reported painful urination, physical discomfort, difficulty walking, and bleeding to be the immediate effects after having undergone FGM/C. In the long-term, some women reported that they suffered from recurring Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and incontinence, which they suspect could be linked to their khatna. Both studies also explored the effect of FGM/C on participants’ sex lives. Anantnarayan et. al. found that approximately 33% of participants believe that FGM/C has negatively impacted their sex life. Similarly, Sahiyo reported findings of 35% of participants who believed that FGM/C has negatively impacted their sex lives. Some of the problems identified by several participants included low sex drive, the inability to feel sexual pleasure, difficulty trusting sexual partners, and over-sensitivity in the clitoral area. Physical consequences of FGM/C in both studies also revealed psychological consequences. Similar to Sahiyo’s findings, Anantnarayan et. al. found that many participants reported feelings of fear, anxiety, shame, anger, depression, low self-esteem, and difficulty trusting people as some of the psychological repercussions of their FGM/C experience. Sahiyo found that 48% of participants in their study reported that FGM/C had left them with a lasting psychological impact. Both Sahiyo and Anantnarayan et. al. also explored the main reasons for the the continuation of FGM/C within the Bohra community. Several common reasons were found, including the continuation of an old traditional practice, the adherence to religious edicts, and to control women’s promiscuity and sexual behaviour. Interestingly, Sahiyo’s study found that 80% of women had earned at least a Bachelor’s degree, no relationship could be determined between education level and having undergone FGC. Meanwhile, the study by Anantnarayan et. al found that a strong connection existed between a mother’s education level and her decision to continue FGC on her daughter. Sahiyo’s study, however, did note that more important than education level was the question of a person’s ideological preference (stated religion) as it might influence a person’s decision to continue FGC on their daughter. In fact, Sahiyo’s survey found that those who were most likely to continue ‘khatna’ were also more likely to still identify as Dawoodi Bohra in their adult life. Anantnarayan et. al also determined that the more diverse personal networks and economic independence from the Bohra religious community a woman had, the more likely they were to discontinue FGM/C and renounce it. Finally, both studies examined the relationship between men and the decision/involvement for a girl to undergo FGC. Both studies did allude to the idea that the decision leading to a girl undergoing FGM/C may not strictly be confined to women. Sahiyo’s study revealed that 72% of respondents believed that men were aware of the practice, but only 27% believed that men were told of the practice when the girl underwent it in their family. Anantnarayan et. al. concluded that men played an integral role in the maintenance and propagation of the practice, both at the personal and political level, whether passively or more actively. However, Sahiyo’s data collection was completed in 2016, prior to the large-scale movement to end FGC in the Bohra community. The last few years have shown that with an increase in awareness of FGC amongst the public, Bohra men’s own knowledge of FGC has also naturally increased, and thus the traditional idea that men are unaware of FGC may in fact be changing with the current generation, as pointed out by Anantnarayan et. al.

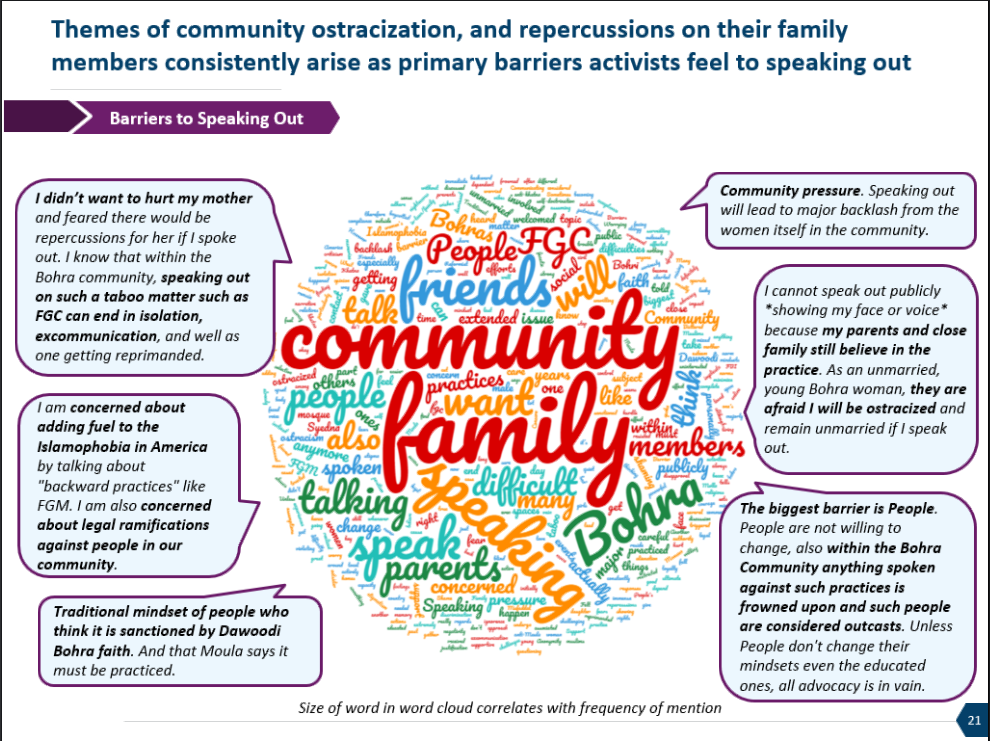

Sahiyo Activist Needs Assessment: Learning How To Support FGC Activists

Research Summary & Implications Background Sahiyo is dedicated to ending Female Genital Cutting (FGC) in the Bohra community, a small global Shia Muslim community. Sahiyo focuses its efforts on public education about the prevalence and impact of FGC, community outreach initiatives, and supporting survivors and activists, with the ultimate goal of driving positive social change around gender violence. Sahiyo recently partnered with a healthcare market research consultancy to conduct primary market research with activists speaking out against FGC, in an effort to better understand activists’ challenges and hopes for the future. In this article, we hope not only to summarize the key findings from our primary research and draw implications for the broader gender violence activist community, but also to underscore the importance of conducting primary research with activists. Research Methodology Research entailed two phases: first, a quantitative, online survey was sent to anti-FGC activists across the globe. Second, follow-up interviews were conducted with activists from the online survey sample, who expressed their willingness to further participate in the research. Sample & Demographics All activists who took part in this research grew up in the Dawoodi Bohra religious tradition, and are now self-described as active in speaking out against FGC (‘khatna’). Phase 1 Quantitative Sample: Between 40-50* activists took the online survey, 91% of whom were female. Activists’ ages varied, though 56% were under the age of 35. The majority (~3/4) of activists reside in either the United States or India and were highly educated, with 96% having at least some graduate degree. Although respondents were raised Dawoodi Bohra, only 43% still identify as Dawoodi Bohra, while 37% are non-practicing. However, 67% of respondents socialize with Dawoodi Bohras at least sometimes (every couple of weeks). 69% of respondents personally underwent FGC, while 94% had a mother who was cut. Phase 2 Qualitative Sample: 7 activists were interviewed in follow-up telephone conversations. These 7 activists had variable ages, countries of residence, and genders. Key Findings Although each activist’s story is unique, they all shared the drive to end FGC in their community and more broadly. Their activist journey typically started with a realization about the prevalence of the practice: whether this be through a family member speaking out, a documentary, or media coverage; the realization sparked further investigation. Although some activists had memories of their own experience of being cut, many did not. For the latter individuals, the realization as adults about the practice’s prevalence occasionally came with a realization that they too had been cut, triggering an intense emotional response. For all activists, the initial anger and shame upon learning of the practice’s prevalence often led them to ask family and friends about FGC in their community, but they were met with a culture of secrecy and silence. Even when activists did open conversations with family and friends, they found the practice was often justified as a longstanding tradition, necessitated by religion. This culture of secrecy and acceptance, paired with painful body or narrative memories of their own cutting, were said to be key drivers to speaking out. Many activists feel that not only does FGC have long-term physical and psychological health impacts, but that it is also a form of child sexual assault and/or abuse given the lack of consent. Furthermore, activists acknowledge that FGC’s underlying misogynistic and patriarchal factors make it part of a larger movement to control women. In short, activists feel that FGC does only harm with no benefit and must therefore be ended. Challenges to speaking out: Overlap of religion and community The most significant challenges activists face when speaking out stems from the high degree of overlap between religion and community in the Bohra community. Although most activists are fairly open with their families and friends about their activism, they feel only moderately supported by their loved ones, largely due to concerns with the activism’s social repercussions. These concerns are linked to the social characteristics of the Bohra community, which include long-standing traditions of loyalty and closeness, in which the religious community often dictates social circles, romantic partners, neighborhood housing, cemetery sites, and more. This overlap causes speaking out against FGC to be seen as an attack on the community and faith at large. As a result, activists fear that speaking out would lead to discontinued social and professional bonds and ceasing of access to religious privileges. For some, these potential social repercussions bar them from speaking out publicly, so they pursue more private means of activism, such as anonymous writing and supporting organizations like Sahiyo. Religious authority Concerns with speaking out are further driven by the authority of the Bohra religious leaders. Considering that there is no clear religious justification for FGC, its continuation relies upon the leaders’ mandates and interpretations. Questioning of the religious leaders is deeply discouraged and potentially dangerous—causing many activists to not only fear speaking out, but also sometimes demotivating them, making them feel that without the support of religious leaders, their activism is a ‘lost cause.’ Considering the challenges above, many activists feel torn between wanting to end the practice and wanting to maintain a close connection to their faith and/or community. Even activists who are no longer involved in the Bohra community still fear risking the social wellbeing of their loved ones. Activists present this as a ‘catch-22’: loyal Bohra members are well respected by their community; however, speaking out against a taboo practice might oust them from it, rendering their authority no longer valid. Conversation challenges When activists do speak out publicly or privately, they find the conversation about FGC particularly challenging. The lack of robust, publicly available information about the practice’s prevalence in the Bohra community, as well as about its physical and mental consequences on the girls’ health often result in other Bohra members undermining the impact of khatna. Many community members present khatna as ‘not as bad as other types of FGC’. These arguments are particularly difficult for activists who do not have a clear memory of their own experience

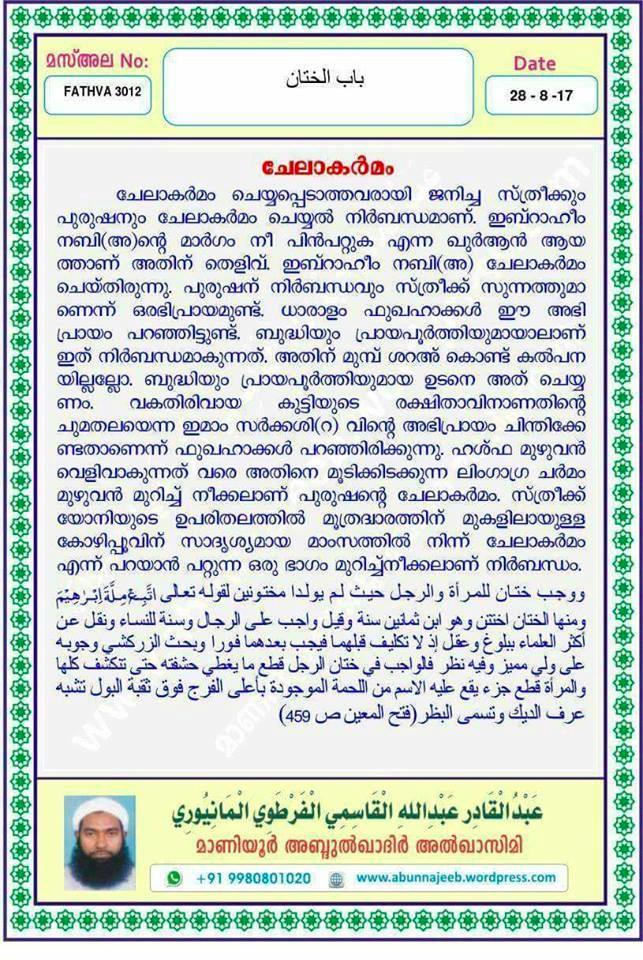

Furore about Female Genital Cutting in Kerala: Impact of Sahiyo’s investigation

by Aysha Mahmood On August 14, 2017, Sahiyo published a preliminary investigative report pointing to evidence that Female Genital Cutting (FGC) – a practice so far associated only with the Bohras in India – is also being practiced in Kozhikode, Kerala. The report was published in both English (here) and Malayalam (here) and it was followed by a furore within the media and social media circles of Kerala. Sahiyo’s report was picked up by all the prominent media houses in the state. Mathrubhoomi, a major Malayalam newspaper, conducted a follow-up undercover investigation at the same FGC clinic that Sahiyo had visited, and confirmed the Sahiyo report. Mathrubhumi’s report of August 27 also provided some additional information about the way that clinic has been performing and propagating Female Genital Cutting: The doctors at the clinic mentioned the presence of a middleman named Ansari who brings women to them for FGC. Mathrubhumi claims to have communicated with some people online who offered to take them to clinics that conduct FGC and also offered contacts of traditional “Ossathis” or cutters. Considering Mathrubhumi is one of the two leading newspapers in Kerala, what followed was an uproar, to put it mildly. Prominent religious leaders came out denouncing FGC and made statements against the practice. The health minister of Kerala, KK Shailaja, has ordered the District Medical Officer and Health Department Director of Kozhikode (Calicut) for a probe into the matter, and has asked them to submit a report at the earliest. The minister has stated that any clinic or doctor found practicing FGC will immediately be punished. On August 27, the Youth League of the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) marched to the Kozhikode clinic in question with slogans and placards, and in the presence of the media, proceeded to close the clinic. The clinic is now dysfunctional. Kerala IMA’s press statement condemning FGC On August 28, the Kerala branch of the Indian Medical Association also issued a press release taking a strong stance against FGC. The Association described the practice as “unscientific and against medical ethics”. The Kozhikode police is also investigating the matter. The city police commissioner has said that it is possible to file a criminal case against the perpetrators of FGC if its victims are ready to do so. In general, all the major political and religious institutions in Kerala have condemned the act and promised support to put an end to such a practice. The former state minister for social welfare, Dr. MK Muneer of the IUML party, has said, “It is very shocking news to hear that something we only thought existed among African tribes, exists also in Kerala. Strict action should be taken against such activities.” A Malayali student, Shani SS, wrote about her personal experience of having undergone FGC, becoming perhaps the first woman from Kerala to publicly share her story of being cut. Her story was published in Mathrubhumi, and mentioned not only her own FGC but also that of her mother, several years ago. Responses on social media Malayalam social media has been buzzing with debates on FGC and the reports in Sahiyo and Mathrubhumi, but people’s reactions have been a mixed bag. The main reaction has largely been disbelief and the usual conspiracy theories of “This is paid news to defame Muslims”, or “because we have not heard of this ever in our lives, it does not exist”. For some, the reaction has been, “to each his own”. But there is also a comparatively large group of people of social media who have openly supported FGC and are doling out religious texts and Fatwas. Most of these people are religious scholars from the Shafi sect of Islam and are quite influential in the interior pockets of Kerala. Some of them have openly attacked the religious leaders who spoke against FGC in the media. One of the prominent faces of Kerala politics and its religious front, Sayyid Munavvar Ali Shihab Thangal (the son of IUML’s former president) was forced to take down his Facebook status that spoke against FGC. Supporters of the practice made fun of his “ignorance of Islamic texts and foregoing his religion for admiration from the ignorant”. Another small-time religious scholar and moulavi, Maniyoor Abdul Kadir Al Kassimi, has been circulating a Fatwa with a Hadith and details on why circumcision is equally compulsory for men and women. This has been found doing rounds on Whatsapp and Facebook and some blogs. The same emotion can be seen reflected in many Facebook posts and comments by Muslim scholars and moulavis from the same sect and community. These have been liked and shared by many people. It is a reason to be concerned that there is at least some level of acceptance and support for FGC amongst a considerable number of followers. Not surprisingly, almost all the voices defending FGC on Malayalam social media are those of men. Women’s voices are nowhere to be heard.

Research Studies on FGC

New Study from Iran: Female Genital Mutilation Impedes Men’s Well-Being Implementation of the International and Regional Human Rights Framework for the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation FGM INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE – RESEARCH – ADVOCACY – POLICIES – ACTION – May 10-11, 2016 – UN Geneva WHO guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: U.S. Assistance to Combat This Harmful Practice Abroad is Limited UNICEF: Most Oppose Female Genital Mutilation Female Genital Cutting in Indonesia: A Field Study State-Of-The-Art Synthesis Report on FGM/C – What Do We Know Now? UNFPA – Demographic Perspectives on Female Genital Mutilation 2015 Annual Report of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Metrics of Progress, Moments of Change Root causes and persistent challenges in accelerating the abandonment of FGM/C Gender equality and human rights approach to female genital mutilation: a review of international human rights norms and standards Female genital mutilation/cutting and violence against women and girls: Strengthening the policy linkages between different forms of violence FGM: A native affliction on every inhabitable continent The Clitoral Hood – A Contested Site: khafd of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) in India Perception and barriers to reporting female genital mutilation How to transform a social norm – Reflection on phase II of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation Study finds ‘huge’ fall in FGM rates among African girls FGM and Social Norms: A Guide to Designing Culturally Sensitive Community Programmes Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Call For A Global Response COVID-19 Disrupting SDG 5.3: Eliminating female genital mutilation Global Platform for Action to End FGM/C: Submission to UN General Report on FGM 2020

Announcement: A new research project on Khatna in Mumbai

by Keire Murphy and Cleo Egli An exciting new research project is being undertaken in Mumbai and its environs this summer which hopes to bring a new perspective to the international discussion of khatna. The project, which is a cultural study on khatna, the Bohra community, and the current activist movement against the practice, is being carried out by Keire Murphy from Trinity College Dublin and Cleo Egli from the University of North Carolina, who has been awarded the Mahatma Gandhi Fellowship in order to complete the project. It will be interesting to see how an entirely external perspective engages with the Bohra culture and cultural specificities of khatna, which is so distinct from the practice portrayed in Western media. The stated goal of the project is to explore and understand not just the practice but also the culture (or cultures) of the Bohra community. The researchers hope that this will enable them to make recommendations to activists coming from outside of the community hoping to work on this issue on how to engage with this issue in a culturally sensitive and culturally specific way. Murphy and Egli claim to have undertaken this project because of the lack of research that has been engaged in not only on the subject of khatna but also on the Bohra community itself, which they believe is an essential step to effecting lasting social and cultural change. For them, “In order to change, we must first understand”. The women want to explore the identities of the members, particularly the female members, who comprise the Dawoodi Bohra community, how the community defines itself, the tensions and divisions within the community as well as its unifying factors. They want to explore the “beauty and pride of the community in order to better understand its controversial underside.” They are particularly interested in exploring the current movement within the community, led by SAHIYO and Bohra women; how the movement is perceived by the people it is aimed at and what factors are integral for a woman deciding whether to continue the long-standing tradition or face the possible repercussions of breaking with the ancient mold; and what distinguishes a woman who simply doesn’t continue the practice from a woman who goes further and actively campaigns against it. This project will hopefully be a significant stepping stone to bringing global humanitarian and academic attention to this issue that has often been overshadowed by African practices that, although put in the same category globally, so little resemble the experience of the Dawoodi Bohra. This project is also hoping to act as a precursor and guide for the more comprehensive studies that this issue deserves. This is an incredibly important time for the Bohra community both within India and Pakistan and abroad, with media attention being dramatically drawn to the issue by the highly publicised arrests of practitioners of khatna in the United States. The community may be facing a large amount of media attention in the coming years and it is the aim of this project to provide the members of the community with an opportunity to set the story straight from the beginning about who they are. The study will take place in Mumbai from June 24 to July 23, 2017, and researchers are calling for research participants, both in Mumbai on these dates or in other parts of India from July 24 to August 7. They also have an open call without date restrictions for participants who would like to engage in interviews over Skype. Participants can be male or female and do not have to speak of their experience of khatna if they would prefer not to. All Bohras are encouraged to participate so that the research will be representative of all groups and opinions in the community. Submissions are also welcome, but interviews will be given more weight. All interested parties should contact mgfmumbai@gmail.com. A part-time translator job opportunity is also available. To view job description, click here.

Part-time Translator Job Opportunity in Mumbai

Looking for an individual willing to assist in translation between Gujarati and English, with a preference for those also able to speak Lisan al-Dawat, for the month of July in Mumbai and surrounding provinces. The translator will be working closely with two student researchers from the University of North Carolina and Trinity College Dublin who will be conducting research on the Dawoodi Bohra community via interviews with different members of the Dawoodi Bohra community. Familiarity with the community and culture of Dawoodi Bohras is strongly preferred, as ideally, the translator would help the student researchers by helping coordinate interviews and acting as a liaison between community members and researchers. Pay will start at ₹ 250 / hour, with an average of 10-15 hours per week of work available. Pay and hours are very flexible. To express interest or for further information, please email CV to: mgfmumbai@gmail.com

Female Genital Cutting exists to preserve patriarchy: A Bohra survivor speaks out

by Mubaraka MotiwalaAge: 18Country: India (This essay was first published on the Safe City blog on January 22, 2017) Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is the ritual removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. Ever wondered why it’s done? Well I did and I found out what a heinous act it truly is. In the summer of 2016, I went for a vacation and discovered that I too was a victim of FGM. This came as a complete shock to me; like a repressed memory it just zapped my brain and froze my memory. I was in the bus having a conversation with one of my Muslim female friends and in the midst of talking about religion she suddenly asked me if I was circumcised? At first I was confused and gave it a good thought but nothing came to me, so I said, “no, that wouldn’t have ever happened to me’’. Saying this, we continued with our conversation. A month later a few people in my community started talking about it and I had a few college classmates come up to me asking me to be a part of the FGM movement or if I’ve experienced it. This led me to really think about this and finally when I was travelling back home one day the memory came rushing in and completely baffled me. I am in fact a victim of this preposterous act and was so utterly unaware and uneducated about it. I was tricked into thinking that I’ll be getting chocolate and instead was taken to a shady-looking dimly lit house, where a lady was waiting for me and my grandmother. The lady asked me to lie down and spread my legs, which was an extremely strange thing for me to do. But my consent and opinion wasn’t taken into account, of course. She pulled my panties down and told me to stay still and that I won’t be hurt at all while my grandmother sat there, watching. And then it happened, she cut my clit and put some antiseptic but that didn’t stop me from crying out in pain and have a bruised vagina. Finally, I was given the promised chocolate and taken back home to forget and mask the day’s event completely. So my question is, why do we perform this practice? Through my research I’ve found out that FGM is practiced by people because it is often considered necessary for raising a girl, and to prepare her for adulthood and marriage. It is often motivated by beliefs that it is imperative to perform this. It aims to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity and in many communities believed to reduce a woman’s libido and therefore believed to help her resist extramarital sexual acts so she can be loyal to her husband. FGM is carried out because it is believed that being cut increases marriageability and is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are clean and beautiful after removal of body parts. Known as Khatna in certain communities, it is considered as a prestigious event and often celebrated and boosted by family members and society. But in reality I think this practice is performed in attempts to control women’s sexuality and ideas about purity, modesty and beauty. The reason behind all kinds of genital mutilation is to restrict female sexual experience. It is usually initiated and carried out by women itself who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to social exclusion and generate rebellious nature. And to my complete utter surprise no religious scripts prescribe the practice. Practitioners often believe the practice has religious support and is good for female health but there are no known health benefits. So the truth is that nobody knows why we practice FGM but because it is imposed on us as a religious responsibility and as our ticket to be accepted and be married, we go along with it. Everybody has been lying to us telling us that this is the right thing to do and beneficial for our future. This entire malpractice is existent to ensure and preserve patriarchy in societies. Us women are always controlled by someone or something for our entire life. This kind of behavior makes us give in and accept the stereotypes that are actually abusive and violating to us. We are manipulated into submission and are to do what someone else commands us. Aren’t we all the creation of god and told that he gives us everything for a reason, then why take away our will and consent to decide if we want this to happen to us or not. What gives anybody the right to take away the will to have their own opinion and purloin a part of someone’s body parts. What gives another person the right to enforce such unacceptable and abysmal rituals! We need to stand up for ourselves, ladies, and show people that we’re not empty vessels and we can’t be controlled to do whatever another pleases. We are human too. Say no to Female Genital Mutilation.

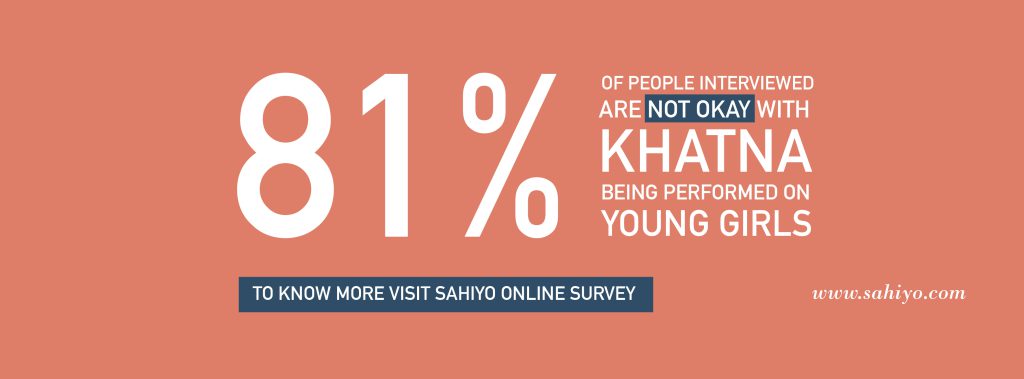

81% want Khatna to end: results of Sahiyo’s online survey of Bohra women