Sahiyo Stories screened in Washington DC: A survivor’s reflection

by Maryah Haidery Recently on Facebook, I noted that real social change usually happens when people are good enough to care about doing the right thing, thoughtful enough to figure out the best ways to do it, and brave enough to actually go through with it. On December 4th, in Washington DC, I was fortunate enough to meet a roomful of such people. I was there representing Sahiyo at an event called ‘Using Data and Community Engagement to Better Focus FGM Prevention Interventions’ sponsored by the US End FGM/C Network and The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health. Maryah Haidery talking at the Washington DC screening. The event included an exceptional presentation by Sean Callaghan from the organization, 28 Too Many on how government agencies and NGOs can use data to track populations where FGM/C may be most prevalent and how best to engage with these populations. It also included a screening of Sahiyo Stories, a series of digital stories by nine different women, including myself, detailing our personal experiences with FGM/C and/or advocacy. I had volunteered to introduce Sahiyo Stories in place of Mariya Taher who was unable to attend the event. Despite some technical difficulties, I tried to summarize Mariya’s history with StoryCenter and the collaboration which culminated in Sahiyo Stories and the short behind-the-scenes video showing how we made the videos and what we hoped to gain from them. Since this would be my first time seeing the videos with a large audience, I was a little nervous. But when Mariya’s voice came on, the room grew absolutely silent and by the end, quite a few people seemed visibly moved. During the Q&A period following the screening, I was struck by the number of people who wanted to know how they could find out more about FGM/C and what they could do to help even though this was not a problem that affected their communities. Afterward, several people from other organizations working to end FGM/C approached me with interesting suggestions on using Sahiyo Stories in conjunction with their apps and projects in order to make a greater impact on government officials or healthcare workers or educators. As I looked around the room at all these people who cared so passionately about ending this practice – people who were good and thoughtful and brave, it made me more confident than ever before that real social change was a real possibility. To learn more about Sahiyo Stories, read: Seeing Sahiyo Stories on Female Genital Cutting Come to Life. The inner-workings of Sahiyo Stories The Making of Sahiyo Stories

Inaugural screening of Sahiyo Stories in California

On October 19 in Oakland, California, Sahiyo, in collaboration with StoryCenter, Asian Women’s Shelter, Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence hosted a screening of Sahiyo Stories that included a behind the scenes short film documenting the women’s experiences in creating their digital stories. Sahiyo Stories involved bringing together nine women from across the United States to create personalized digital stories that narrate experiences of female genital cutting (FGC). These nine women, who differ in race/ethnicity, age, and citizenship/residency status, each shared a story addressing a different challenge with FGM/C. Some women who had only recently discovered they had undergone FGM/C were grappling with its emotional and physical impacts, while others were invested in advocacy to prevent it from happening to more girls. The collection is woven together with a united sentiment and a joint hope that the videos will build a critical mass of voices from within FGM/C-practicing communities, calling for the harmful practice’s abandonment. A panel discussion on female genital cutting followed the screening, and the greater connection FGC has to gender-based violence. To learn more about Sahiyo Stories, read: Seeing Sahiyo Stories on Female Genital Cutting Come to Life. The inner-workings of Sahiyo Stories The Making of Sahiyo Stories

Sahiyo Stories to host first screening in Oakland, California

On October 19 in Oakland, California, Sahiyo, in collaboration with StoryCenter, Asian Women’s Shelter, Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence will host a screening of Sahiyo Stories with a behind the scenes short film documenting the women’s experiences in creating their digital stories, followed by a panel discussion on FGC. To RSVP for the event, visit http://bit.ly/SahiyoStoriesOct As a reminder, the project brought together nine women from across the United States to create personalized digital stories that narrate the experience of undergoing female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and/or the experience of their advocacy work to end this form of gender violence. You can watch all these brave women’s stories by visiting the Sahiyo Stories YouTube Playlist. If you’re interested in learning more about the project or hosting a screening of Sahiyo Stories, contact mariya@sahiyo.com

‘I Hope my Story Helps other Women’: A Reflection on the Sahiyo Stories Workshop

Break the Silence on FGC Soumou in New York

From March 24-25th, Sahiyo Cofounder, Mariya Taher, spoke on Fireside Conversation – Seeing is Believing: Story Telling and Media Engagement to end FGM,” during the Break the Silence Soumou in New York City organized by There is No Limit Foundation. The event was held in commemoration of Women History Month and the United Nations 62nd Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62). A “Soumou” is a Malinke word for “gathering.” Traditionally, the Soumou is an opportunity for building unity, creating a collective goal, and remembering the past through storytelling. It is also a moment to dream about the future and to learn lessons that will lead to realizing the dream. This was the goal of Break The Silence Soumou. The weekend included workshops, strategy sessions, and cross-sectional movement building aimed at ending FGC in the U.S..and at unifying grassroots organizations, as well as, survivors, and allies in the movement to end FGC.

Calling for Visual Artists, Musician, Sound Designers, to assist with Sahiyo Stories Project in the U.S.

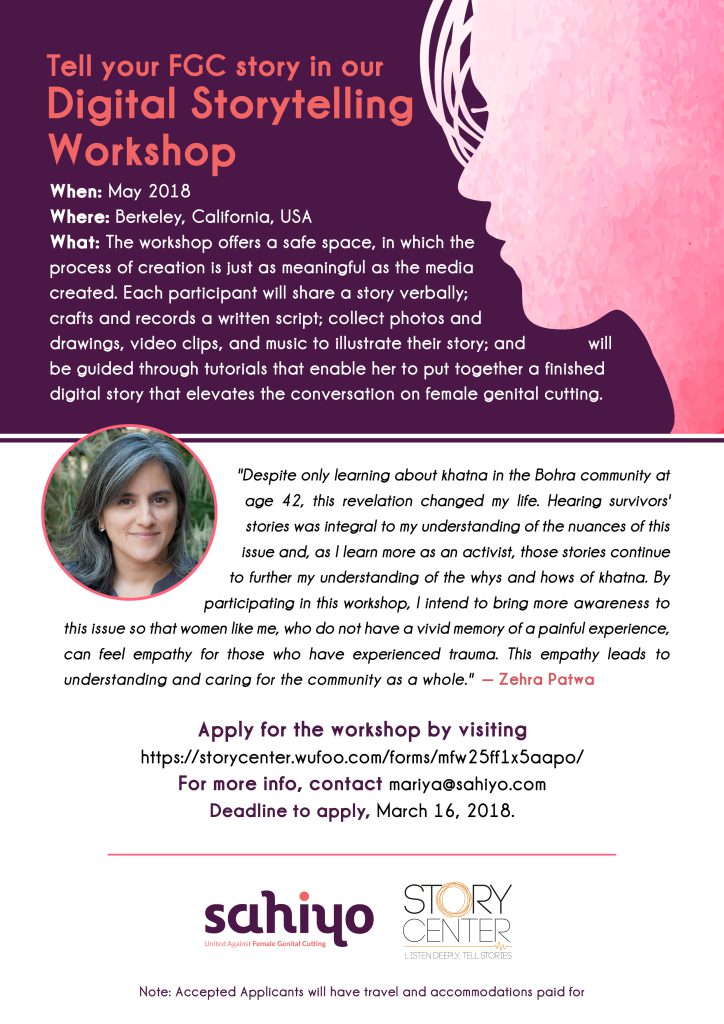

This May, 2018 Sahiyo Cofounder, Mariya Taher, will be working with StoryCenter on a digital storytelling project to capture the stories of women who have been experienced or affected by FGM/C. Here is an example of the story format that will be used — simple voiceover narration paired with images and video clips. The stories will be shared as a way of bringing attention to the need to end this practice, which continues to harm women and girls around the world. Sahiyo and StoryCenter are looking for talented visual artists (illustrators, photographers, videographers) to develop original visual images to use in the short videos that participants will be creating. They are also looking for talented sound designers and musicians who might be willing to contribute original music to include in the videos. The workshop will be in Berkeley, California, however, photographers and videographers do not necessarily need to be at the workshop; they might shoot creative b-roll video in their own locations, of scenes/things other than the storytellers. However, they are also considering the possibility of asking workshop participants to take part in short interviews so we capture how the experience of how the workshop is going for each of them. In this case, one videographer would need to be present at the workshop in May. If that person also wanted to help shoot some b-roll on site, that would be welcomed. If you or someone you know is interested in participating and supporting this important project, please contact Mariya at mariya@sahiyo.com. Please note that due to limited funds, Sahiyo Stories is seeking individuals who may be able to provide assistance on a pro-bono basis (though there may be a slight possibility of providing a small stipend). Sahiyo and StoryCenter would, of course, would ensure that your contribution is properly credited in our project (and on the participant videos produced). To learn more about the project, click here. To see an example of StoryCenter Video, click below [youtube url=”https://youtu.be/1GtBKX1a1fA”]A

The undecided: Conversations with survivors of Female Genital Cutting in Pakistan

By Hina Javed(This is the fourth part in a series of essays by Hina Javed on her experience of reporting on FGC in Pakistan. Read the whole series here: Pakistan Journal.) My conversations with survivors had by now made it clear that the more answers I received, the more questions arose. Wrapping my head around Female Genital Cutting (FGC) was not going to be easy as I had, up till that point, been presented with two extreme views of FGC with little room for middleground.I found myself diving deeper to uncover the truth behind a practice which spanned centuries; a curiosity fuelled my quest to get to the very origins of such an invasive practice. From the outside, the Bohra community seemed united, but I found the more I scratched at the community’s surface, the divisions and differences of opinion on FGC became evident. Publicly, the Bohra community will protect their own; quietly, they dissent amongst themselves. Getting to the bottom of this practice had become more than an assignment for me. The following day I found myself sitting in the drawing room of an elderly lady who belonged to the Bohra community in Karachi. Here was 65-year-old Mrs Sumaira*, ready to answer all my questions without a hint of doubt or hesitation: “Aunty, what is your opinion on female circumcision? Is it right or wrong?” “Well, I cannot comment on the moral and legal implications of the practice. It is not for me to decide. All I know is that circumcision is sanctioned by our community leader. I am not entirely sure if it is right or wrong, but I believe the decision should be left with the child,” said Mrs Sumaira. “What about you? Did you get your daughter circumcised? Did you inform her prior to her circumcision? How did you feel when she was finally cut?” I asked without bothering to check my train of thought or questioning. “I was in my early thirties when the pressure to get my little one cut started building inside me. I knew it was supposed to happen sooner or later. I feared a backlash from the family elders if I delayed it any further. It was a rite of passage and my daughter had to go through it. My only, and probably biggest fault, was not telling the truth to an innocent child who thought she was going to a lady doctor for a routine check up. I told her they might perform a small operation if they found a ‘bug’ down there. I deeply regretted lying to her when I saw her bleeding and in pain,” she told me somberly. “Why did you regret? Was it only the pain that made you feel guilty or was it something else?” I asked. The answer she gave me came ridden with doubt. Sumaira believed she had little choice all those years ago. “Maybe this wasn’t the right thing to do. Maybe I took something away from her; something that actually belonged to her the minute she opened her eyes. I could have given it a second thought, but I was overwhelmed with uncertainty and wanted to get it out of the way. I knew I would get a lot of raised brows if I avoided it altogether. In fact, I would have been ostracised from the community,” she added. My line of questioning had ruffled some feathers, and I became more determined to seek answers. “Aunty, forgive me if I am being too intrusive, but didn’t you say you believed it was a necessary rite of passage?” Sumaira explained that the decision she took for her daughter, without the latter’s consent, was in the girl’s best interest. “I believe it depends on the type of society you live in and the level of exposure you get growing up. It’s true that circumcision lowers the libido and you have no right to take that away from an individual. However, it becomes necessary to control that drive if the girl is growing up in a conservative society like Pakistan. If she goes ‘astray’, she would be called names and looked down upon. Besides, she would also have to suppress her desires which could ultimately lead to psychological issues like depression and anxiety,” she said. “Does that mean it is more of a social requirement than a religious ritual in the Bohra community?” I asked, confused. Sumaira’s reply made it clear she was also confused. “It could be, but I am not entirely sure about that. I believe it’s good if you get it done. However, there is an element of choice which people did not realise back in the day. People who are growing up in a free society and have liberal mindsets could either do away with it or let their child decide.” Sumaira continued to speak but her response left a deafening silence from me. It became difficult to detach myself emotionally and focus on that interview. Therefore, I targeted my final question at just that; breaking the silence. “Then why do you think breaking the silence will help? Why did you decide to speak about this issue in the first place? How will it change the narrative?” I asked apprehensively. “It’s just the question of expressing yourself. If you disagree with the practice, you should be able to voice your opinion without being bashed by others. And if you want to go for it, then there’s no one stopping you. In either case, there’s no reason for it to be a hush-hush affair. There is more awareness, education and freedom of expression in this day and age. You’re free to make your own decision,” she concluded. The hour-long question and answer session with Sumaira left me more confused than before. My search for the right answer was becoming fruitless with every interview, but, in the midst of it all, I realised that three categories of people existed in the Bohra community when it came to FGC: the decided, the

How I learned that FGM happens in India

By: Anonymous journalist whose friend underwent FGM Age: 26Country: India “It was supposed to stop me from me doing ‘those things’. I’m not sure if it served the purpose,” M told me. I would have known about this practice much later if I hadn’t met someone who underwent it. As we were getting to know each other, one day M drew my attention to the fact that she was different from other girls. That was when I heard the term female genital mutilation for the first time. “You should read about genital mutilation”, she said. Later that night, I learned about this horrible practice meant to oppress women. I had so many unanswered questions for her. ~ How did she become a part of this? ~ Explaining what happened to you to all your companions must be tiring… ~ Was everyone as sensitive as me when she told them about what had happened to her? ~ Why does a well-educated family still practice it? I called her. That’s when I heard her story. She told me that men don’t take part in ‘matters of female’. She was only six or seven when her maternal grandmother took her for khatna. She thought they were going for afternoon prayers until the point when an old lady laid her on a table and pulled her pants away. But the real terror struck when her legs were pulled apart. All reasoning was silenced just like her protest and this memory was repressed. What does a child know about right or wrong? If the elders do it, it must be for good. Right? “Where was your mother when all of this was happening, did she even know?” I asked her. M said, “I don’t know. She hadn’t joined me when it was done to me. I can’t imagine her watching me go through something like that.” Her mother probably didn’t want to inflict the pain on her, and at the same time, her mother could see there was flawed reasoning behind the practice. Her mother accepted that the tradition had to continue in silence. Life went on as usual until M turned twenty. She was no longer a little girl. After she had sex for the first time, the repressed memories came up. She could no longer hide. She wondered, are my genitals different, am I different because of it? M often felt she was not normal and even felt she was asexual. It was not just the altering of her genitals that made her feel different, but the lack of understanding of her body as well. “Remember I would often wonder if I was asexual because of it? Well, those doubts are gone. I finally know I have the urge to have sex like anyone else,” M said to me to explain the doubts she had around her ability to orgasm. She still remembers the first time her family openly talked about khatna. M was in college and an aunt was visiting from abroad. She heard her aunt speaking to her parents about the “mindless practice of female circumcision.” She joined the conversation, speaking publicly for the first time about her anger for having undergone it. But the conversation ended with her parents saying the following words “Daughter, you will understand later. It has to be done so that the girl doesn’t go out of hand.” Like within most families in India, parents and their children do not speak about sexuality. She couldn’t let her family know she was sexually active. I sense that because parents see pre-marital sex as wrong, this idea has a very big role in the continuation of the practice. Therefore, while addressing FGM we can’t separate it from the need for sex education. Sex education must also include sensitizing the emotional and psychological aspects of sex as well. “How can we bring an end to all this?” I asked her the last time we spoke. “One thing is for certain,” M said. “I am not making my daughter go through this.” Her decision is significant. Pledging not to continue it on the next generation is important, particularly when perhaps twenty years ago, many women never made this pledge. “Will you ever talk publicly about it?” I asked her. “I don’t know”, she said, “It’s not like I’m not trying to make any difference. I just feel I’m not ready to be public and deal with the attention I would get afterwards.” Her answer made me realize that the people who are affected by the reckless act are not the only anchors of social change. We needed to focus equally on institutions that allowed such harmful traditions to continue. Speaking to the religious heads about FGM is important. The most crucial aspect of reforming this age-old practice is educating people. Simply banning it by law is not the solution because this may lead some families to carry out khatna in secret, on their own. She said, “Today’s young priests who get more educated think like us. I’m sure if they are encouraged to bring about changes, it will have a larger impact on the community.” As a journalist, I’m sharing the story of my friend, because I believe the media’s role is critical in achieving social justice, and helping to get those larger institutions to think about creating change.

‘Girls must be circumcised or they will grow up loose’: Three Sri Lankan women talk about Female Genital Cutting

by: Bintari Hamza Zafar, a concerned Sri Lankan Muslim citizen Country: Sri Lanka Female Genital Mutilation is a serious problem in Sri Lanka. Almost all Sri Lankan Muslim women are circumcised. Both Moors and Malays (ethnic Muslim communities in Sri Lanka) are of the Shafi school of Islam which regards female circumcision, or “sunnat”, as compulsory. They account for 98% of the local Muslim population. The Bohras who follow an Indian leader called Syedna also practice it very strictly. Local Bohras number about 3,000 people. The All Ceylon Jamiyathul Ulama (ACJU) which is the Supreme Council of Muslims of Sri Lanka has declared female circumcision obligatory in a fatwa in Tamil பெண்களுக்கு கத்னா செய்தல் (Pengalukku Khatna Seydal) and are very strict about it. I also heard that the Bohra leader Syedna has said it must be done. Local Muslim girls are circumcised on the 40th day of birth or a little later. Bohra girls are cut between 7-10 years of age. The amount of genital cutting differs from child to child. The operator is a woman called Ostha-maami. Usually, they nick the clitoris for a little blood to come and leave it at that. Educated families get it done by lady doctors who cut off part of the foreskin of the clitoris. But more severe mutilation also takes place and has been reported to us. I give below some interviews that I recently conducted with women of my community. Banu Mariyam (40 years, name changed) Muslim girls must be circumcised or they will grow up to be loose. I have two daughters and got them circumcised when they were babies. The local Ostha woman came and did it. She took a large needle and pricked the clitoris till the blood came. She then wiped it and put some grey powder. I think it was ash. She told me the blood has to come out or the girl’s clitoris will be big, and she will always touch there and grow up to be a loose woman. I don’t regret it. All our girls must be circumcised. See Western ladies, see Princess Diana, how many men she had affairs with. Our women are much more decent. That is because we take the blood out and make it small. Then they can control themselves. Fathima Nilufa (33 years, name changed) I did not know of this practice till my daughter was born. My mother said she must undergo sunnat. I told her only boys undergo sunnat. She said no, girls also. Then she brought home the lady doctor, who cut my daughter. My baby cried a lot. The doctor put some kind of white powder on the wound and said it will heal. Later I noticed baby’s clitoris was pink and swollen. I got angry and asked the doctor what she had done. She said she removed the skin over it like she did for the small boys. She said nothing to worry. It healed a little later. She is ok now, but I am still angry because my daughter was hurt. I don’t know why they do it. My mother said it must be done for Muslim people. Sameena Begum (29 years, name changed) I was married to an Aalim (religious scholar). A few days after my wedding night, he said he wanted to see my private part before having sex. Then he got angry and said I was not circumcised. He even shouted at my mother. My mother kept saying she had got me circumcised as a baby, but he did not listen. He brought home an old Ostha-Maami in a taxi and ordered her to cut me. My husband held one leg and forced my mother to hold the other leg while the Ostha-Maami cut me. My mother was crying and told me not to scream as the neighbours could hear. It was very painful. I wish my mother had got it done properly when I was a baby.

‘Far from enhancing my marital bliss, khatna had all but devastated it’

by: Anonymous Age: 30 Country: United States I first learned that khatna had been performed on me when I was 11 years old. My mother told me, and even then the hair on my neck rose and I had a clear instinct that what had happened wasn’t right. I asked my mother why Bohra girls were cut when there was no evidence that it had the same benefits as male circumcision. She responded with the familiar refrain: hygiene, marital bliss. At that time, I had no idea what a clitoris was supposed to look like. My mother described it to me, never using that word, but saying that it was a “long thread of flesh” that hung out of the vaginal hood. It had to be cut because it would otherwise rub constantly against my underwear. For the Potterheads out there, the image that sprang to my mind was of an Extendable Ear in my panties, a long flesh-colored string that had to be snipped to curb continuous arousal. I had never seen a picture of a clitoris, nor could I. I’d grown up in a country where the Internet was heavily censored and the chapter on reproduction was ripped out of our Biology textbooks. That image of the clitoris as a long flesh-colored string stayed with me until I looked at cartoon pornography as a teenager in the United States. But let me be clear, because this detail about my education is a gateway to Orientalism: I had an excellent primary education, and I was far better prepared for graduate school than many of my US-educated peers. The fact that schools in that region refused to include human reproduction in the curriculum was shortsighted and foolish, but not unlike the abstinence-only curriculum I’ve learned about since moving to the US. But let me return to that moment my mother told me I’d been cut: since it never crossed my mind that I would or could be sexually active before marriage, I only thought about khatna once or twice a year until I was married. And that’s when I realized that sexual intercourse was extraordinarily difficult for me. My vagina would convulse, and even the thought of using a tampon triggered these convulsions. My condition went undiagnosed until years later when my OB/GYN attempted to do a pelvic exam. She had no warning because I did not tell her about my difficulty with intercourse. Peering over the stirrups, she apologized for causing me pain, and asked me to breathe deeply while apologizing rapidly: “Just one finger, I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m so sorry almost done almost done, and relax.” I learned that I had vaginismus, and needed physical therapy. As I talked through my condition with my wonderful doctor, I learned that an early childhood trauma was likely the cause for my vaginismus. The symptoms pointed towards a psychological trigger rather than physical limitations, and the more I reflected on my condition the clearer it became that I had always been unable to tolerate even the idea of penetration from around the age khatna had happened to me. Any kind of insertion seemed laughable to me as a teenager, whether I was washing myself in the shower or attempting to masturbate. This points to the idea that women who don’t consider themselves victims – and I certainly didn’t and don’t – can experience long-term effects of khatna that we may not even (or ever) be aware of. When I eventually saw a picture of a healthy and anatomically accurate clitoris for the first time, what I’d already suspected was confirmed: there was no hygiene-related reason to snip it, and far from enhancing my “marital bliss” it had all but devastated it. But learning about khatna revealed something about me to myself: even as a child, I recognized the value of empirical research when it came to making decisions about altering bodies – particularly female bodies, which have historically always been more vulnerable. Even as an 11-year-old, I knew the benefits of male circumcision – I had just learned about trench warfare during World War II, and the infections that raged among uncircumcised men living in those filthy conditions. And as I reflect on that moment when I was 11, it makes perfect sense to me that I chose a career in research. Another thing I recognized is that not only is the term “victim” disempowering when referring to women who have experienced khatna, but also entirely inaccurate. Activists have argued against the term “victim” for decades, particularly when it comes to describing women and gender-queer survivors of physical abuse. However, the term is misleading too. It is an easy label assigned by the status quo, and a particularly effective way for those in power to demonstrate their investment in “women’s issues.” It is a gateway to continued imperialism, where the narratives of marginalized groups are stripped of nuance, or hidden entirely. It has been incredibly easy, even comforting, to vilify Dr. Jumana Nagarwala for performing khatna in the US. But let us not buy into the clash-of-civilizations narrative. Each time a US news outlet says the practice will not be “tolerated in the US,” there is an implied comparison to those “backward” countries that tacitly endorse it. Additionally, it implies a wounded nationalism, where (White, male) individuals are almost more outraged that it is happening in the United States than that it is happening at all. And so we are forced to view the practice through an imperial lens. We must not let khatna become a political talking point for US politicians to show how they have “zero tolerance” for “brutal” practices while forwarding a facile concern for women’s rights. We must not forget that khatna is endorsed by the largely male leadership of the Bohra jamaat. While Dr. Nagarwala is culpable, and there is no question that she must face legal action, she has been turned into a scapegoat by both US discourse and the Dawoodi Bohra leadership.