The story of my start to the holy month of Ramzan

by Insia Dariwala, Sahiyo Ramzan — the time of peace, love, and prayers; a time for family gatherings, breaking fasts together and collectively praying for individual good, and the good of all in this world. Unfortunately, this Ramzan is showing me exactly the opposite, as I see the entire Bohra community (well almost), rising up to bring us down, in the guise of reinstating religious freedom. Over the past few days, as this circus on social media unveiled, I have been inundated with text messages, phone calls and emails about how Sahiyo is being talked about at every community gathering. We are being called names, our personal lives are being attacked, our religious loyalties are being questioned, and anyone who speaks for us is being targeted with a lot of viciousness. Many of those who speak for us have come back to us feeling saddened and helpless. Helpless because they want to stand up to the bullying, but are very afraid of the verbal attacks on their parents, on their relatives, and other family members. They are afraid of the humiliation, of the subtle ostracism, and the backlash from their jamaats, so they choose to stay anonymous. Anonymity has its own comfort. It allows you to speak up. It allows you to have a voice, and that’s exactly why we have so many girls and women who have chosen to let go of their right to be visible, only to stand up against this practice. They choose to live the duality of having a voice, and yet pretend they are voiceless, because that is the only way they will be accepted into the fold. For these very reasons, when I am asked why I, or my other Sahiyo girls, are not responding to the ‘Sahiyo is not my voice’ campaign against us, my answer to them is very simple — we never ever claimed to be anyone’s voice. We just made space for the women who wanted to have a voice. Why then are all these people feeling so threatened? It amuses me to see how a few voices of dissent could become such a big threat to an entire community. I am also amused to see the kind of efforts put into creating content to beat us up, acquiring social media handles, blocking our social media handles, and going to such great lengths to reinforce their identity. It’s sad to see how our attackers are just dismissing what so many women went through after they were cut. This backlash is exactly what prevents survivors of any trauma to share their stories. The pain endured may or may not have been the same for all, but the shame which they are being put through for speaking up about it, is the same. Unfortunately, it also reminds me of what so many survivors of domestic violence, child sexual abuse, and rape go through. It’s always the fault of the one who went through it. “She should have shut up.” “She should have been clothed more appropriately.” “She should have never disobeyed her husband.” And so the cacophony of society’s empty culture and tradition continues. Would it be safe to then say this has nothing to do with ours or anybody else’s religious beliefs? Would it also be safe to say that it’s disheartening to see, how an entire community’s faith rests on what’s cut between a girl’s legs? Is faith so weak, that it requires to be enforced through archaic and harmful traditions carried out thousands of years ago? Is it so weak that one needs to resort to bullying, and exploitation, in order to sustain its own existence? This message is for all the women who want this practice to continue — You can hate us all you want, and trick yourself into believing that you are doing this for your religion. But no religion practices hate. No religion asks you to put someone down to look good. No religion asks you to hurt, humiliate, threaten, and isolate someone who has a different point of view. Religion is what you ‘are’, not what you ‘pretend’ to be. It is about forgiveness, compassion, empathy, and the ability to reach out and accept. Today, as you pray while breaking your fast, do ask yourselves, Am I all of this? Then and only then, will it truly be the month of Ramzan.

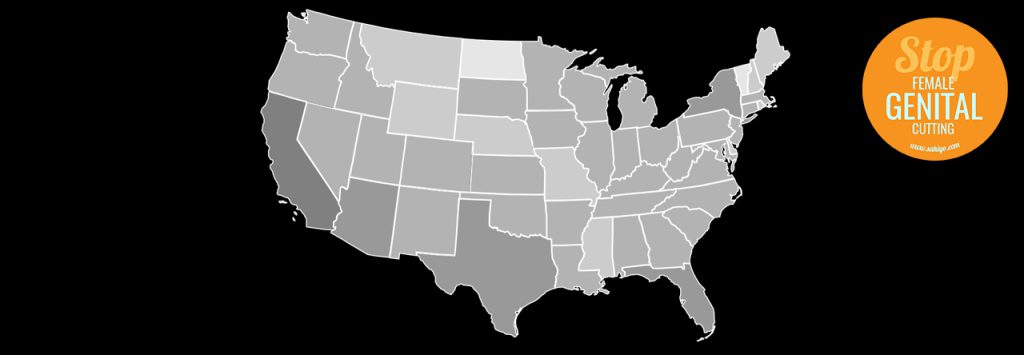

FGC in the United States

2024 Dozens of patients file suit against former OB-GYN and Cedars-Sinai, alleging misconduct Upgraded charges in child torture case Implementing Survivor-Led FGM Law In Washington State Coalition against female genital mutilation supports victims in Washington state 2023 Connecticut is 1 of 9 states without a ban on female genital mutilation. Thousands are at risk, activists say Infographic: Women’s Health Needs Study (WHNS) 2022 US bill equates healthcare for trans people with female genital mutilation On the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation 2021 Equality Now Fact Sheet: Female Genital Mutilation in the United States U.S. toughens ban on ‘abhorrent’ female genital mutilation Houston woman faces historic indictment over female genital cutting Keeping Girls at the Center: Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation 2020 Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment of Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting in Girls 2019 Activists Launch the First Anti-FGM Network in the US U.S. woman says strict Christian parents subjected her to FGM Female Genital Cutting in Immigrant Children — Considerations in Treatment and Prevention in the United States US House Votes to Recognize FGC as a Human Rights Violation 4 women with lives scarred by genital cutting: Could a surgeon heal them? It’s All About Health for Women and Girls: Ghada Khan on Ending FGM The Doctors and Parents Arguing for Female Circumcision in the U.S. Court declines House Democrats’ motion to intervene in Michigan genital mutilation case 2018 To Combat Female Genital Cutting in the U.S., We Need More Information FGM in the US: The Hidden Crime Next Door FGM Legislation by State ICE leads efforts to prevent female genital mutilation at Newark Airport Judge dismisses female genital mutilation charges in historic case Letters: Other views on FGM Historical Overview of U.S. Policy and Legislative Responses to Honor-Based Violence, Forced Marriage, and Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting 2017 New York Cracks down on Female Genital Mutilation The Tipping Point: Can the World End Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Genital Mutilation also occurs in the US, activists call on states to make it illegal Metro Detroit doctor charged with performing female genital mutilation on young girls US Doctor Arrested in Michigan on FGM Charges Michigan case shows more needs to be done to confront female genital mutilation Detroit Doctor and Wife Arrested and Charged with Conspiring to Perform Female Genital Mutilation Genital Mutilation victims break their silence: ‘This is demonic’ I Underwent Genital Mutilation as a Child -Right Here in the United States Female Genital Mutilation Isn’t a Muslim Issue. It’s a Medical Issue The Female Genital Mutilation Scandal Tearing a Community Apart Michigan Case Adds U.S. Dimension to Debate on Genital Mutilation Genital Cutting Victims Get Backlash for Condemning Taboo Ritual It Happens Here: The Reality of Female Genital Mutilation First-ever federal charges of female genital mutilation seen as landmark Cutting Young Girls Isn’t Religious Freedom House Increases penalty for female genital mutilation 2016 Genital mutilation risk triples for girls and women in US, CDC study finds Underground: American Who Underwent Female Genital Mutilation Comes Forward to Help Others With 500,000 female genital mutilation survivors at risk in the U.S., it’s not just someone’s else’s problem 2016 Violence Against Girls Summit on FGM/C Ending Violence Against Girls: Giving Innovative Leaders the Resources They Deserve 2015 Underground in America: Female Genital Mutilation 2014 Bill Maher Doesn’t Know That FGM Is on the Rise in the West

Four American survivors of FGC speak out

Four American survivors of Female Genital Cutting have broken the culture of silence around the issue through a new video. These women, from diverse backgrounds, illustrate that FGC is not restricted to any one geography, religion, or socioeconomic class. The four women featured in the video produced by the U.S. Department of State Bureau of International Information Programs include Renee Bergstrom, F.A. Cole, Aissata Camara, and Sahiyo co-founder Mariya Taher. In order to realize the UN Sustainable Development Goal of ending FGC by 2030, we need not only more courageous survivors need to speak out, but we also need religious leaders, men and boys, health practitioners, and young people to join the global campaign. To watch the video, click here.

Engendering Progress Event Honours Sahiyo Co-founder

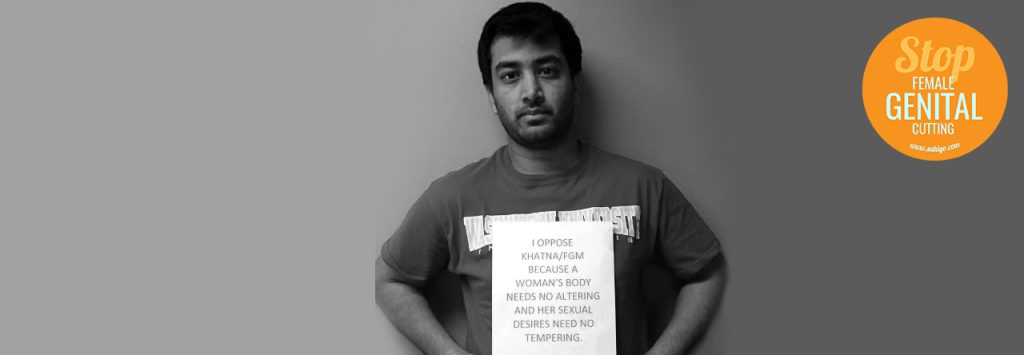

Why the khatna conversation needs men’s voices too

(First published on June 7, 2016) by Ammar Karimjee Age: 24 Country: Pakistan I found out when I was 19. I’d just heard about the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in an Anthropology class, and had dismissed it as something that simply happens in rural African villages. After class, I’d expressed disgust to a friend about it, something along the lines of “Can you believe people still do things like this?” The friend was a fellow member of the Dawoodi Bohra community, who in this moment realized I must not have known. After she spoke to me about it, I remained in disbelief. I was sure she must be wrong. I reached out to my mom and sister, and after a few in-depth conversations with them, it settled over me. A mix of emotions – anger, frustration, humiliation – all overcame me simultaneously. I didn’t do anything at first, I just needed some time to let it all sink in. After I’d had time to process, I realized I needed to do something. At first, most of my involvement in my personal anti-FGM campaign came through conversations with people I knew, primarily men. Even in this initial stage, I realized how essential it would be to effectively engage men as part of this movement. Over time, I became involved in a few more formal networks that were also working on this issue, and through these, I’ve had the chance to speak at the United Nations on this issue as well as be a small part of the This American Life podcast a few weeks ago. It’s been an amazing journey to be a part of. Below, I’ve shared some of the major learnings/thoughts I’ve developed over the last 5 years. I hope it can serve as a way for some of you to help think through this topic. If you have questions, there are a ton of us here to help guide you to the answers. If you’d simply like to talk further about this, please do not hesitate to reach out. You can always contact Sahiyo at info@sahiyo.com to become connected to others working on ending FGM. Some men don’t want to even engage in the conversation about FGM. Part of this is because they dismiss it as an unimportant issue at face value, but I believe a larger part of this may have to do with the discomfort that comes with talking about the female body and the lack of knowledge that it results in. As men, we do not intuitively understand the female body and the biological processes that occur within it. Of course, we never will be able to truly know what being a woman feels like, but by gaining an understanding of how their bodies work, we can begin to have an idea. Naturally, we compare things that happen with a woman to its closest direct male counterpart. As such, we associate FGM, or circumcision as many people chose to incorrectly refer to it as, as the equivalent of male circumcision. This is a dangerous fallacy for men to turn to in their justification. The function of the male penis and a woman’s clitoris are not identical – not even close. Further, the benefits that come from male circumcision are simply not present in FGM. Please, please, please, do your research and understand the impact of this practice. It is terribly important for men to be aware of women’s bodies – not just specifically to be able to understand FGM, but for so many other reasons, health and otherwise. For the men who were willing to talk about it, one constant held true – they had never talked about it before. Creating a space to have these conversations became an important part of the larger effort to engage men. But the snowball effect definitely holds true. Individual conversations I was leading turned to group conversations I was just a part of. Soon after, conversations started happening without me there at all. Awareness of FGM in the Bohra community has increased exponentially since I started speaking about this issue, especially in the last few months. However, the conversations happening are still dominated by women. It is of course amazing that so many women have started sharing their stories and thoughts. But we still live in a patriarchal context. Religious leaders are still men. Decision-makers in families are still largely men. We – the men – MUST start caring. We don’t have the option to be silent or ambivalent anymore. We can not keep pretending that it isn’t our problem. These are our friends, our daughters, our sisters, our mothers, and our wives. Read their stories. Understand what FGM is and how it affects them. Once you do, you’ll be as angry as I am. You won’t want it ever happening to anyone you’re close to. We can’t undo what has already happened to hundreds of thousands in our community – but we CAN prevent it from happening from this day forward. To men everywhere – Start reading. Start talking. STOP FGM.

I was cut, but today I am proud to be standing up for myself

(First published on March 16, 2016) Name: Alifya Sulemanji Age: 42 Country: United States I, Alifya Sulemanji went through the atrocity of Female Genital Mutilation. It’s been 35 years but I haven’t forgotten that day of my life even today. One morning my mom told me we were going to visit my aunt who lives in Bhendi Bazaar in Mumbai, where many of the Bohras live. In the midst of the day my mom, aunt, and her daughter (my cousin) told me that they were taking me somewhere to remove a worm from me. I was barely 7 years old then and didn’t know what they were really talking about. I blindly followed them. We entered some building and went up the stairs and got into this lady’s house. I had no clue what was going on. They told me to lay down on the floor assuring me that it was so they could take out a worm from my body and it was going to be very simple. My mom told me she was so devastated, she decided to leave the room and wait outside. They took off my underpants and I saw the lady remove a brand new sharp Topaz blade from the wrapper. They caught my legs and hands so I couldn’t move. I was watching them innocently, not knowing what’s going on. In a few moments, I was screaming in pain. My private part was in terrible shooting pain and I was crying. They told me to be quiet and I would be fine. The lady dabbed some black power on my cut area to stop me bleeding. After the procedure was done I was told to keep quiet; it was a secret not to be told to anyone. But today I am sharing my experience with the world. My life has been different since then. Not that I am not happy and successful, but it has left some everlasting effects on me. I have two lovely daughters. Most of the time I am paranoid about their safety and protection. I keep getting bad thoughts that someone might harm them. People have judged me as an overprotective and possessive mom, but they don’t know where it’s coming from. My husband told me that sometimes at night when we are sleeping, he hears me cry in my sleep. Many times I get nightmares about my daughters being in trouble and I wake up screaming. I have unknown fears and phobias. I have seen a psychologist regarding this. Today, I am happy and proud for standing up for myself.

We must realise that there is an alternative to khatna

by Insia Jaliwala Age: 18 Country: India The experience of khatna, not only the actual act but the implications of the practice, was a gradual revelation for me. In the vague haze of childhood memories, that particular day stands out. I must have been around 6 or 7 years old. My parents told me I could miss school that day and were taking me out, I was obviously very ecstatic. I was taken to a ‘lady doctor’; a gynecologist who applied a red serum on my hand with a cotton bud and asked if it burned. It did. She then proceeded to do the same to my genitalia. I remember the moment when she told me to remove my pants and lie down on the bed. “It’ll be over in a minute,” she said while holding a scalpel in her hand. There wasn’t much bleeding and I don’t even remember the pain. What I do remember is an inhibiting confusion and fear. That day isn’t registered in my memory as a traumatic event, but a day I associate with a sense of loss. That day an important part of my womanhood was snatched away from me. That day my body was mutilated without my consent. The reality of the twisted practice struck me only a few years ago when I got into a conversation with my elder sister who told me about her experience, which was much worse and painful. After, I started to explore the subject more. I read about female circumcision and came across horrifying stories from Africa. I stumbled into many stories of khatna told by the women around me. I had started to understand the terrifying implications of the practice which differed from person to person and the physical and mental trauma some of my own sisters and close friends had to go through, and are still going through. I also came across many justifications for the practice, some from my family elders which went along the lines of, “This is done to curb a girl’s sexual desire so that she can put her mind to other things”, among many others. All of this left me with an overwhelming sense of betrayal. My family, my community, had failed me. As I dwelled into it more, I realized that this act of oppression had (as with any other social issue or phenomenon) multiple dimensions and was woven in a convoluted fabric of culture, custom, and tradition. Earlier this year, as a film project for college, I decided to make a documentary on Khatna. During my research for the film, I came across Sahiyo and was amazed by the fact that so many women were willing to share their stories on this platform. My initial thought when I decided to make the film was that no woman would want to talk about this on camera. To my surprise and glee, many women around me agreed to be a part of it. There are hundreds of women (and men) out there who want this barbaric practice to stop. There needs to be a discussion about this on a communal level and people of the community need to realise that they have an alternative, they can choose not to impose this upon their young ones.

A letter on khatna by a young Bohra man

by Anonymous Age: 28 Country: United States Hello All, Firstly, I would like to start by telling you how ashamed I feel of being so ignorant about the issue of female khatna and how honored I am to be a part of a family whose women are spearheading the fight against FGM. I am from an Islamic Dawoodi Bohra family that comprises mainly of women. I have six beautiful sisters. They have all undergone khafd (khatna). Back then, there was no awareness and there was tons of social pressure. Everything was done quietly and no one spoke about it. At least in my community, it was a given that a girl child had to have her khatna done. Not doing it would be condemned. Women who have gone through FGM have started talking about their experiences. Openly speaking about this issue has done great good for the community as it has helped build awareness and made folks like me, who were ignorant about it, read and learn more about it. I salute the women who have been bold to talk about this. Thank you! Listening to these experiences makes me really sad. Sad because this has been going on for so long and this practice has absolutely no foundation. It makes me sad that educated people never questioned it and were so socially engrossed that they just did what they were told to do. It makes me sad because it just proves how sexist the world is (which I do not want to believe). It saddens me because parents are still putting their daughter through this. For my religious friends: the Quran does not even mention khatna. So please do not put a religious aspect to this practice. This practice only has side effects. For those who are not aware – please please read here. More importantly – it is her body, please respect it. This issue is important and it must be dealt with. It needs support from each and every member of the community including the men.

They told me they would call a ‘bhoot’ if I didn’t stop screaming

(First published on February 26, 2016) by Fatema Kabira Age: 19 Country: India Seven years old. I was seven years old when they forced me to have a part of my femininity cut off. I don’t remember much from my childhood. My memories are very vague. Yet, despite my poor memory, I clearly remember the day I was circumcised. That day is a vivid memory. My grandmother and mom told me I was going for a sitabi (a celebration for women and girls). I used to love sitabis when I was a kid. So, I got really excited and eagerly awaited going to the sitabi. I even insisted to my mom that I wear my new clothes and topi. After dressing up in my favourite clothes, I left with my grandmother and mom to go to the sitabi. We didn’t end up attending any sitabi and instead we went to a place that was unfamiliar to me. It was an old looking building. The steps were covered with dust and were broken. I was confused why we were there. We went inside somebody’s house and were greeted by a middle-aged woman whom I failed to recognize. I asked my mom what was going on, but she ignored me. The house was small with only one room, kitchen, and a storage unit attached to the ceiling. The one room was dim and gloomy and gave out an eerie feeling. The Aunty chatted with us for a while and then went inside another room to bring something back. When she came out she had a blade and 2 or 3 other items in her hands (I can’t recall what they were). She came and sat in front of me. My mind went blank. I thought, ‘Blade? For what?’ My grandmother then asked me to remove my pants. Innocently, I told them I did not want to use their washroom. My 7-year-old brain could not comprehend any other reason why my grandmother would ask me to remove my pants. And that too in front of an unknown woman, since my grandmother knows how shy I was even in front of my own mother. But I obliged my grandmother’s request. They made me lie down and held my hands firmly to the ground. The next thing I remember is the sight of the silver blade and a sharp agonizing pain in my most intimate area. I screamed in terror. What did they do? The Aunty told me to keep quiet or she will call the “bhoot” (ghost) that stayed in her storage unit. I didn’t oblige this time. I screamed and yelled and tried to free myself. It was all in vain. They did what they wanted to do. It was all over. I cried all the way home. It hurt every time I urinated. The sight of the blood made me sick. I was hurt and angry and confronted my mother about this. She told me she was under religious obligation and she did what thought was the right thing to do at that time. Fortunately, I didn’t face any medical repercussions due to the unhygienic and brutal way in which I was circumcised. But it has left a psychological impact on me. I feel disgusted, ashamed, and angry at what has been done to me. There is no reason that justifies this barbaric practice. There is no reason that justifies taking away women’s inherent physical rights and ability to experience pleasure. Young girls are scarred for life and this needs to be stopped.

I am grateful I was able to talk to a therapist about my khatna

(First published on January 6, 2016) by Anonymous Age: 30 Country: United States I was not more than seven years old when I recall going into a medical complex on a quiet Sunday afternoon accompanied by my mother and our family friend. My mother told me it was time for my “khatna” or circumcision. She explained it as a rite of passage, something all the little girls in our Dawoodi Bohra community had to do. I remember feeling scared but I didn’t know exactly why. I just had a feeling something terrible was about to happen to me as our friend unlocked the building with her keys and we continued into her desolate practice. We went into one of the brightly colored rooms where alphabet wallpaper boarded me in. I started crying before it even happened while she crooned, “all I’m going to do is remove a liiiitle piece of skin.” Totally exposed, I was asked to relax and read the wallpapered alphabet backward. My mother helped hold me still while I was flat on my back and in hysterics. The snip which took maybe half a second was followed by a sharp-shooting pain that seemed to last in that moment, for eternity. I bled for three days and then it was over. It wasn’t until I was nineteen, the end of my freshman year in college that I stumbled upon an article from one of my classes, describing the experience of a woman who had been a victim of FGM, or female genital mutilation. After reading the article once, I was immediately reminded of that Sunday afternoon twelve years prior. There was no way the same thing could have been done to me. My seven-year-old perspective of a little piece of skin being removed was analogous to that of a piece of skin from the top layer of the palm of a hand. My cousin used to stick a needle through that top layer and tell me it was magic that the needle was sticking there. She eventually revealed her secret and showed me the protective top layer that separated her hand from the skin. I guess like that layer, I always figured it would grow back. Still, the feeling of uncertainty drove me to call a couple of peers and academics in my community to ask whether our “khatna” was in fact, a partial removal of my clitoris. Their answer confirmed the worst of my fears. My next concern of “how much?” tormented me, and after a frantic visit to the school nurse, I got my answer: “There’s only a remnant left,” said the nurse practitioner who examined me. *** I don’t believe my discovery was adequately addressed the first time as the rest of my college experience was consumed by bouts of grief, rage, frustration, insecurity, and depression. My feelings only grew stronger as I got older and had more encounters with the opposite sex. My overcompensating, defensive attitude permeated all aspects of my life—friends, family, work, and academics. It wasn’t until my mid-20s when I shared with my gynecologist during a routine visit what happened to me, that I was given three names of specialized therapists in the area with whom I could speak about my concerns. My insurance provider at the time would not cover therapy. Fortunately, one of three therapists agreed to see me for a discounted out-of-pocket fee because she was interested in my case. To this day, I am so grateful for the opportunity I had to talk through what happened to me in a safe space as such resources and treatment were unavailable to me at home or in my community. I learned it was ok to talk about sex, explore my sexuality, and sexual feelings. I was even prescribed homework to assist me in doing so. At the time of the therapy, I had been sexually active and my partner, who was incredibly supportive, was also invited to participate in one of my sessions. When growing up, I never thought I would have sex before marriage. The idea behind the circumcision was to curb any sexual appetite I might have. Ironically, once I learned this had happened, I wanted nothing more than to have sex to see what my capabilities were. While I was incredibly nervous and insecure about having sex, I was more open to losing my virginity in the context of a serious relationship, which is how it happened for me. One of my main insecurities about sex was that I felt like I was driving without the headlights on. Often times, I didn’t know where to go or how to guide my driver. I felt like a failure. To this day, I still have not experienced orgasm. While sex is enjoyable for me and I could describe what I can achieve as a “mini-climax”, I am bothered by the fact that I may never get to experience this wonderful part of life. While it’s no secret many women who have not been “circumcised” struggle with the same issues, a part of me will always wonder if that would have been true for me had this not happened. I will never know.