Wrestling with trust and fear in regard to female genital mutilation

By Farzana Esmaeel Country of Residence: United Arab Emirates Trust and fear are two emotions that have an interesting correlation to input and output of human behavior. One emotion, trust, establishes safety and comfort for individuals whilst the other, fear, displaces the very premise of safety and comfort. At the age of 7, you don’t articulate emotions; you feel them. And your mother is your beacon of trust. She loves you, comforts you, cares for you and sacrifices for you. Then, when trust is removed, it’s only natural to feel extreme pain and deceit at her hands the most. My sister and I were taken to a dilapidated, dimly lit building at the far end of the city on the pretext that we were going to meet an aunt for a check-up. At the tender age of 7 when mum tells you we are going for a check up you don’t appreciate entirely its meaning, and at the time it meant to me that we were going to see a doctor. What followed was unprecedented, and a memory that will be etched in our minds forever. Sadly. The pain was too much to bear as 30 years ago, female genital mutilation (FGM) in the Dawoodi Bohra community was generally more practiced under callous and less “sterile” ways. (Yet, even today, when it is practiced by licensed white coat doctors under more hygienic conditions, it doesn’t make the practice correct.) The overarching feeling I took after my experience 30 years ago was deceit. My mother is a simple, non-confrontational, less informed person, who at the time of my sister and my cutting, played into the hands of a community (mindset) that propagates fear: fear of being ‘ostracized’ for not having FGM done, fear of her daughters being ‘impure’, fear of standing up against cultural norms and practices. Though today, this same woman hasn’t once told either of her daughters to carry out this inhumane practice on her granddaughters. She now understands the pain and futility of it all. FGM is a practice entrenched with ‘fear,’ stripping human ‘trust,’ and inculcating in young girls early on to be apologetic about their sexuality and their desires. It is on us to be the change. We must question this violation of human rights and ensure that we raise our voices against this harmful practice, not just for our daughters, but the many more daughters all around us.

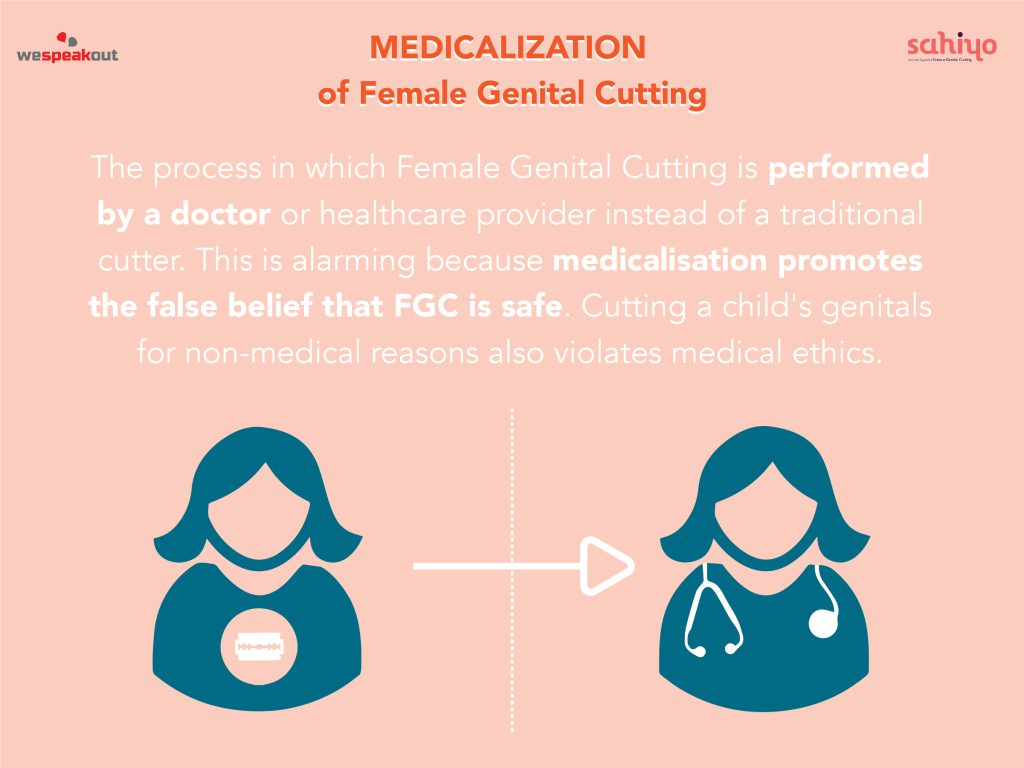

The Disturbing Trend of Medicalising Female Genital Mutilation

by Lorraine Koonce-Farahmand In the Zero Tolerance campaign to end Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), what has been noted is the arc of progress. Increasingly, women and men from practising groups have declared support for ending FGM; and in several countries, the prevalence of FGM has decreased significantly. A BMJ Global Health study reported that the rates of FGM have fallen dramatically amongst girls in Africa in the last two decades. Using data from 29 countries going back to 1990, the BMJ study found that the biggest fall in cutting was in East Africa where the prevalence rate dropped from 71% of girls under 14 in 1995, to 8% in 2016. Some countries with lower rates – including Kenya and Tanzania, where 3-10% of girls endure FGM – helped drive down the overall figure. Nevertheless, UNICEF’s groundbreaking report shows that whilst much progress has been made in abandoning FGM, millions of girls are still at risk. Flourishing against this backdrop is the compromise of medicalisation of FGM that competes against progress in the Zero Tolerance Campaign. A disturbing number of parents are seeking out healthcare providers to perform FGM. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), medicalisation is when a healthcare provider performs FGM in a clinic or elsewhere. Such procedures are usually paid for under the assumption that medicalisation is not FGM, and is done to mitigate health risks associated with the practice. Consequently, in recent years, the medicalisation of FGM has taken place globally, particularly in Egypt, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Mali, Nigeria, Northern Sudan, and Yemen. In many of these countries, one-third or more of women had their daughters cut by medical staff with access to sterile tools, anesthetics, and antibiotics. The non-governmental organization, 28 Too Many has investigated the involvement of health professionals and has highlighted what must be done to reverse this trend. 28 Too Many reported that the medicalisation of FGM in Egypt is an enormous challenge. Currently, 78.4% of incidences of FGM in Egypt are carried out by health professionals. Egypt had the highest rate of health workers performing FGM at 75%, with Sudan at 50% and Kenya at 40%. A 2016 study by The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the Africa Coordinating Centre for the Abandonment of FGM/C (ACCAF) also found that FGM is increasingly being performed by medical practitioners. Parents and relatives seek safer procedures, rather than outright abandon FGM. The medicalisation trend has conveniently forgotten that FGM violates women’s and children’s human rights to health, to be free from violence, to have the right to physical integrity and non-discrimination, and to be free from cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment. The “just a nick” is essentially gender-based violence (GBV). What is being “nicked” is still part of a woman’s labia majora, labia minora or clitoris. The medicalisation of FGM perpetuates that women are inferior human beings. This is not in harmony with international human rights standards. There is also clearly an economic incentive for promoting medicalisation. Medical personal perform it for financial gain under the premise that if the crux of the issue is the health side effects and pain, by using sterilised instruments and medication the problem has dissipated. The misguided assertion that medicalisation is a viable option is ignoring the fact that all types of FGM have been recognised as violating human rights. These rights that have been codified in several international and regional treaties mirror worldwide acceptance and political consensus at various UN world conferences and summits. Committees such as The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, (CEDAW), the Committee on the Rights of the Child, and The Human Rights Committee have been active in condemning FGM. Medicalisation goes against the principles enshrined in these treaties and conventions. The disturbing medicalization trend continues to argue that this less severe form of FGM can protect girls and women from harm. This was echoed in The Economist article of June 18th, 2016, ‘Female Genital Mutilation: an Agonising Choice’Female Genital Mutilation: an Agonising Choice’. In the article, it was asserted that because three decades of campaigning for a total ban on FGM have failed, a new approach is warranted. The article advocated “nicking” of girl’s genitals by trained health professionals as a lesser evil. This reasoning was echoed in the Journal of Medical Ethics by two U.S.-based doctors, Dr. Kavita Shah Arora, Director of Quality, Obstetrics, and Gynaecology at the MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, and Dr. Allan Jacobs, Professor of Reproductive Medicine at Stony Brook University. They wrote that “we must adopt a more nuanced position that acknowledges a wide spectrum of procedures that alter female genitalia.” They assert that they do not believe minor alterations of the female genitalia reach the threshold of a human rights violation. They also asserted that the nicking of the vulva and removing the clitoral hood should not be considered child abuse. They posit that by undergoing these acceptable procedures in the U.S. during infancy, girls can avoid the risk of being sent abroad for more extensive procedures. These doctors and writers from influential respected journals are often held in high esteem by decision-makers, policy-makers, and experts. However, the advocation of medicalisation grotesquely undermines the hard and courageous work undertaken to end FGM worldwide. The medicalisation trend has ostensibly failed to recognise that the proposal of removing the clitoral hood and “just nicking” the vulva contradicts the WHO’s statement that there is absolutely no reason, medical, moral or aesthetic, to cut any part of these exterior organs. There are compelling reasons why the medicalisation of FGM is fundamentally wrong. The medicalisation is and would be carried out on young girls between infancy and the age of 15. Medicalisation is an attack against the sexual and psychological integrity of young girls. Many are not in a position to say no, unable to give informed consent or to effectively resist the practice. Medicalisation reflects a deep-rooted inequality between the sexes and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women.

My decision as a mother to not cut my daughters

By Masuma Kothari Country of Residence: United Kingdom A vivid memory of my cut has lived through so many years that I can recall the entire act. This experience always intrigued me and it did lead me to the insights of child psychology as to how tender a 7-year-old is. Even though my personal experience was not very excruciating, I clearly remember the sense of betrayal, and it never went away. I was never convinced with the benefits theory that was proclaimed, and honestly, nobody really knew at a deeper level the real reason to follow this practice when I sought guidance. Because of the social influence, it was apparent that herd mentality, unexposed details, unquestioned thoughts promoted this practice. When my elder daughter was near the age, I had to figure out for myself if my daughter should also be cut. It felt as if I had Godlike power to alter something natural belonging to my daughter’s body forever, and that did not feel right. For me, the decision was a chaotic fight between the cultural beliefs and the scientific quest. I reached out to a few of my doctor family members to understand if there was any scientific aspect. All of them discouraged the practice. That is when the light in my heart beamed strong. I chose courage and discussed this openly within my group of Bohra friends. Surprisingly, I found most of the women were also against it and this strengthened my defiance! In fact, my mother secretly regretted having the practice done to me, too. I was sure I did not want to take away what God had bestowed on my daughters. With this clarity, I announced it to my family that we won’t be conducting this on our daughters. One additional powerful advantage was that we resided in the United Kingdom. Since it is a criminal offence here, it was an easy argument to assure a few of our noisy family members back in India. Because we as parents were strong, nobody really questioned or bothered to enforce this. It was simply about standing up for what we thought to be correct. My husband was firm from day one that he was not willing to get this done for our daughters, yet he had given me the ownership of making this decision in case I was convinced that it had to be done. My decision scale had a chunky weight on anti-FGM, which was also a major influence in my decision to not cut my daughters. There is absolutely no need to do this. If you are a parent struggling with the obligation to have this done, just say no to this age-old trauma-enabling practice and move on guilt- free with loud pride that you have made the right choice.

A Nigerian Nurse’s Perspective on Female Genital Cutting

By Brionna Wiggins Female genital cutting (FGC) occurs in many countries around the world. Through my future posts, I hope to explore a few of these places by meeting with those who can speak on them. Many African countries and countries in the Middle East have been reported to have a large concentration of practicing communities. However, FGC is not limited to these areas, nor is it practiced by every single person in these regions. Recently, I spoke with Uzokau Chukwu, a registered nurse, about her thoughts on FGC. Brionna Wiggins with Uzokau Chukwu Mrs. Chukwu is from a community in Imo State, Nigeria, where she spent her childhood until age 13, before moving to the United States. To her knowledge, FGC was not practiced in the place she grew up. Instead, her community does an alternative practice, a tradition entirely without blood or cutting, where the area above the pubic bone is massaged. “Older women in my village says it’s to reduce the sensation of a girl being overly sexed,” she said. “They don’t cut anything.” According to her community, it still meets the security needs of those who fear raising a promiscuous daughter without cutting away at the body. Mrs. Chukwu didn’t hear of FGC until she came to America and began her medical studies later in life. She worked alongside a student who came from a country with a high prevalence of FGC, so the topic was analyzed through an infection-control perspective. The practice of FGC brings up health concerns, as girls may be laid directly on the ground for the procedure, and there is risk of severe injury or death. The operation may be done in a setting without sterile equipment. “People were saying that some girls are dying after they go through that procedure,” she said. “They bleed to death or, you know, they cut so much nerve or into something, and then the places where they’re doing those things are not clean.” Additionally, Mrs. Chukwu is left to ponder a handful of questions. How do practicing societies know if FGC works to reduce sexuality? Do they have alternatives? Did they notice a vast difference between those who are cut and uncut? Who came up with this practice? Who deemed it to be right? More importantly, who asks the girl for proper consent? I agree with Mrs. Chukwu that FGC might be a slightly different matter if FGC was limited to consenting adult women rather than young girls. However, the idea of “cutting into someone’s body,” especially having to hold down the person as the procedure goes on, is disturbing. Although it goes without saying (I still asked), Mrs. Chukwu wouldn’t have herself, her daughters, or anyone else undergo the procedure. She wondered in passing if she was being too harsh in judging those who have their girls cut, but she also demanded concrete evidence that the cutting had any medical benefits at all. Ultimately, Mrs. Chukwu fears that FGC perpetuates the second-class status of women worldwide. The conversation on FGC is definitely opening up to the general public on a worldwide scale as awareness grows. Admittedly, it’s hard to convince others to abandon FGC, as to do so is to challenge their beliefs, especially since it’s a practice that has persisted for generations. Hopefully, increased advocacy against FGC will spike awareness of its detriment to women and society. More on Brionna: Brionna is currently a high school senior in the District of Columbia. She likes drawing, helping others, and being able to contribute to great causes.

A mother’s side of the story on female genital cutting

By Priya Ahluwalia Priya is a 22-year-old clinical psychology student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences – Mumbai. She is passionate about mental health, photography, and writing. She is currently conducting research on the individual experience of khatna and its effects. Read her other articles in this series: Khatna Research in Mumbai. The proverb, “It takes a certain courage to raise children,” rings true, especially since much of the responsibility for a child’s development rests solely on the parental system. The parents significantly influence a child’s development, since the social connection formed with them serves as the prototype for all their future interactions. Through this parental interaction, the child learns values, traditions and learns to understand the culture. Within the cultural context of India, much of this responsibility shifts onto the shoulders of the mother. Due to the proximity and consistent presence of the mother, the child is naturally attuned to her and views her as their primary caregiver responsible for providing love, warmth, and protection. Any adversity experienced by the child may be seen as the mother’s inability to fulfill her responsibilities. Similarly, in the case of khatna, which is a custom among the Bohri Muslims in India which involves partial or total removal of the clitoris, girls may subconsciously blame their mother for failing to “protect” them, although women understand that culture and tradition are responsible for the pain they experience. In my own research, when I conversed with participants I found that even when another female member takes them to be cut, the blame rests upon the mother alone. Initially, I found myself puzzled on this discrepancy in attribution. But during in-depth conversations with my participants, I found that all of them “trusted” their mothers to love them and to protect them. They stated that their mothers had “broken my trust” by continuing a practice without even attempting to understand its implications. Thus, the participants were angry because they had been betrayed. This experience has been discussed significantly in other research, as well. However, I wondered about the kind of emotions elicited in the mothers who were at the receiving end of their daughter’s anger. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to talk to mothers. Through conversations with them, I found that even the mothers have been significantly impacted by the revelation that they had done wrong to their daughters. From a mother’s perspective, her world is crashing down as well. Through all these years she has developed a belief that khatna is good. It may make her daughter belong to their community. it may keep her safe. She acts on this belief with good intentions of protecting her daughter and doing what she believes is her motherly duty. As her child grows up, she does many such acts with good intentions to protect and love her daughter. Throughout her life, the mother forms the belief that I am a good mother who has checked off all the boxes. Several years later, she may find herself in a situation where she is now bearing the brunt of her daughter’s anger because she has failed to protect her child from harm, particularly of khatna. This revelation shatters a belief in khatna she may have fostered for more than half of her life. In therapy, we always say that beliefs are the most difficult psychological construct to work with because all beliefs are interconnected. These interconnections form the self of a person. When one belief is broken, it causes a chain reaction where the other beliefs begin to be questioned. The same happens with a mother. Post-revelation she begins to question every aspect of her life, her identity, and her essence. A mother may then feel an overwhelming sense of failure and inadequacy. Biologically speaking, whenever we are overpowered, our fight or flight responses kick in. Therefore, the mother may respond to her pain with anger and denial. It is helping her keep her sense of integrity intact. When the mother responds in anger and denies having done anything wrong, the impact it has on the survivor is severe It heightens her emotions. It’s important to remember that both the mother and the survivors are fighting their own battles. Both parties need time to process this shock. Thus, it is essential that the space for change is provided by both sides. Some of the pointers to remember during this time that are applicable to both the survivors and the mothers: Remain empathetic. Both of you may be struggling. Be kind. Do not raise your voices while talking. Do not accuse each other. Listen when the other person talks. Both of you have the right to say your part. Have conversations outside the purview of khatna. Establish some routines with each other: eat together or go for walks together. Respect each others’ decisions. The dynamics of a relationship are bound to change once such an intense conversation takes place. It is essential that during this time of transformation, a sense of support for each other is established. At the same time, it may be difficult to do so, but it is imperative that this be done if the new dynamics are to mimic the love, warmth, and comfort that may have been present in the previous relationship. My participants themselves mentioned that although the dynamics between them and their mothers have changed, with time and space their bond has only become stronger. A message to the survivors, you have the right to be angry. You have the right to be heartbroken. Give yourself time to feel all these emotions. Take care of yourself. Access some helpful resources. For mothers who regret their decisions but do not know what to do, apologizing always helps. Not only would it heal you, but it may heal your daughter, as well. For mothers in the dilemma of whether they should perform khatna on their daughters, please don’t do it. A life full of pain and regret is no way to live, neither for you

Reflections on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting & Intergenerational Trauma

By Anonymous Country of Residence: United States I am not a survivor of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). In fact, my father is vehemently opposed to the practice. Even though I was shielded from FGM/C, I know loved ones who have undergone the procedure. One of those survivors is my mom. My parents are from Somaliland, which lies on the northwestern part of Somalia, but we now live in the United States. FGM/C has evolved into a cultural practice in Somaliland that has strong social roots. There is a lot of stigma if you aren’t cut (guilt, shame, neglect). My experience within the Somali community is that FGM/C has been discussed within the realm of religious theology as an acceptable form of practice. The only problem is that there is no religious text in the Quran that advocates or allows this practice. Granted, FGM/C is practiced around the world for a variety of reasons. But it is vital to highlight our personal experiences which will enable us to find collective solutions to end the practice. I didn’t know much about FGM/C until I immigrated to the United States. The irony is that it’s a common practice passed down through generations, but it’s a closely guarded secret. No one talks about it unless it’s your time to undergo the procedure. After I looked into the different forms of FGM/C and the harmful effects, I was immediately repulsed by the actions of my community. I was enraged that the perpetrators of FGM/C were not held accountable for committing a human rights violation. I just can’t fathom how my community would eagerly rally against islamophobia, but turn a blind eye to FGM/C. I faced a dilemma. I was harboring these feelings against my community because I just couldn’t understand the rationale of the people who are advocates of FGM/C. I was concerned that my emotions were clouding my judgment. One day I built up the courage to ask someone who could provide me some context: my mom. I am not sure why I waited until the end of this year to ask my mom why FGM/C is so prevalent in our community, but perhaps I was petrified of how she would react. I was fortunate to have the guidance of Mariya Taher (co-founder of Sahiyo) to prepare me for this day. The type of FGM/C procedure that my mom endured is common amongst Somali women. Known as infibulation, it is typically the most severe form. My mom was very candid in her experience as she vividly disclosed the trauma and pain she went through. During our intense conversation, I interrupted her because at some point, it was too painful to digest. In the end, she confided in me. “We weren’t educated at that time, and we just did what we thought was right,” she said. We can’t trace when the practice of FGM/C had its initial roots in my family, but something clicked inside my head in relation to intergenerational trauma. My grandmother was exposed to the same FGM/C procedure as my mom. Despite the agony, my grandmother is convinced it was the right thing to do. After all, that’s all she knows. Even though my grandmother made the decision for my mom to go through FGM/C, it doesn’t mean that she is a terrible individual. If I had to describe my grandmother, the first thing that would come to mind is her independence. She is fierce, loving, generous and vocal. She would never hesitate to express her opinion. It’s a shocking that my grandmother advocated for the practice of FGM/C because it just didn’t fit in with her persona. This is where intergenerational trauma comes into effect.You endure a traumatic experience and one of the ways to cope with that specific experience is to normalize it. If you are not provided the proper mechanisms to manage trauma, it will manifest itself often at the expense of your loved ones. For a long time, I believed that FGM/C was only practiced in my community. Then I was exposed to data that demonstrated the wide reach of FGM/C. I believe that education and dialogue are crucial to creating solutions for the practice to end. We must not shame communities, but bring awareness of the life threatening risks associated with the procedures that so many girls endure. I believe in humanity and even though the practice of FGM/C is harmful, there is still room for hope.

Is the Dawoodi Bohra community truly as progressive as it claims to be?

By Saleha Country of Residence: CanadaAge: 45 Having lived in South-East Asia, and being exposed to multiple races and cultures, I grew up in a very open-minded family. As a child, my family and I occasionally went to the local Bohra mosque to socialize with others in the community. I loved going to the “masjid” – there I got a chance to meet my best friend and also eat delicious Bohri food. It was wonderful to see all the aunties dressed up in “onna ghagra” which are colourful skirts with matching chiffon scarves draped around the head. After the prayers, everyone congregated outside and chatted into the late hours of the night. Then suddenly in the early 90s it all changed. The upper echelons of the Bohra clergy instated new rules. The progressive Dawoodi Bohras were no more; instead, women were forced to wear a form of hijab called “rida” and men were made to sport a beard, wear a kurta, and “topi” or a cap on their heads. The clergy, headed by the Syedna, began to exert control over everything. Permission from Syedna was required not only for religious matters but in daily life as well. For example, permission was needed to start a business, get married or even to be buried. Female Genital Cutting or khatna was deemed necessary, even though that act of it is not prescribed in the Koran. If any of the rules were not followed, or if you protested and spoke against them, you were excommunicated or threatened to be. You’d lose all your ties to friends and family forever. I can never forget the awful day, when I was seven, while on a holiday in India, my aunt asked me to go shopping with her. She took me to a dingy place where a Bohri man and woman took me inside. They asked me to undress waist down, and when I protested, the man held my hands while the woman removed my jeans and underwear and forced me to lie down. I saw the man take out a blade and I struggled and screamed for help, while they proceeded to cut me. I lay bleeding on the floor, unable to comprehend what had happened to me. It was horrific, painful, and demeaning. I hated what was done to me. I hated that my mom was not there. I was angry at my aunt for allowing them to hurt me. I remember that experience vividly and to this day I am infuriated that I had to go through this ordeal as a child in the name of religion. While the majority of the Muslim communities around the world have spoken against this, the Dawoodi Bohra religious authorities urge continuing FGC under the guise of cleanliness. The worst part is that some women push this practise on vulnerable children too young to give consent, instead of protecting them as adults should. It was a difficult time for me. Having grown up with all the freedom in the world, it was suddenly being taken away from me and I grew cynical of my Bohra culture and wanted no part of it. Today, I am happy I decided to leave the fold. It was not hard to leave. In fact, it was liberating. I was not comfortable with the more rigorous path that my community was taking. I am sure there are many other Bohri people out there who are quietly questioning many of the beliefs handed down to them – some so silly, useless, and others very damaging – Bohris must refrain from using Western toilets; Bohris cannot host or attend wedding functions in secular, non-Bohra venues; brides can apply mehndi only an inch below the wrist and cannot hold the traditional “haldi” functions; and all Bohris must carry a RFID photo ID which will monitor attendance to the mosque. Humanity has achieved such remarkable progress. We have ventured into space, developed cloning and gene editing technologies, and most importantly, the Internet has resulted in globalization and interconnection between various cultures and communities. In this light, I wonder why we are still talking about FGC and the right to choose to do it to our daughters in this day and age? I am thankful that organizations like Sahiyo and We Speak Out have become a voice for children who are being hurt in the name of religion. I look at my children and I see the most informed, connected, and progressive generation. Imposing impractical, harmful religious rules such as continuing FGM on such a generation will only drive them further from our culture. More and more Bohri women and men are speaking out against this harmful practise because whenever religion becomes too rigid, too corrupt, it begins to crack. My hope is that our community can find the strength to break free from all the rigid practices and once again become the most progressive community among the Muslims.

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 6: Effects of FGM/C on the Lower Urinary Tract System

(This article is Part 6 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Julia Geynisman-Tan, MD Background FGM/C has no known health benefits, but does have many immediate and long-term health risks, such as hemorrhage, local infection, tetanus, sepsis, hematometra, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, obstructed labor, severe obstetric lacerations, fistulas, and even death. While the psychological, sexual, and obstetric consequences of FGM/C are well-documented (refer to prior posts in this series), there are few studies on the urogynecologic complications of FGM/C. Urogynecology is the field of women’s pelvic floor disorders including urinary and fecal incontinence, dysfunctional urination, genital prolapse, pelvic pain, vaginal scarring, pain with intercourse, constipation and pain with defecation and many other conditions that affect the vagina, the bladder and the rectum. Urogynecologists are surgeons who can both medically manage and surgically correct many of these issues. FGM/C and Urinary Tract Symptoms One recent study from Egypt suggested that FGM/C is associated with long-term urinary retention (sensation that your bladder is not emptying all the way), urinary urgency (the need to rush to the bathroom and feeling that you cannot wait when the urge comes on), urinary hesitancy (the feeling that it takes time for the urine stream to start once you are sitting on the toilet) and incontinence (leakage of urine). However, the women enrolled in this study were all presenting for care to a urogynecology clinic and therefore all of them had some urinary complaints so it is difficult to tell from this study what the true prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms are in the overall FGM/C population. Therefore, given the significant number of women with FGM/C in the United States and the paucity of data on the effects of FGM/C on the urinary system, my research team studied this topic ourselves in order to describe the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in women living with FGM/C in the United States. Publication will be available online in December 2018. We enrolled 30 women with an average age of 29 to complete two questionnaires on their bladder symptoms. Women in the study reported being circumcised between age 1 week and 16 years (median = 6 years). 40% reported type I 23% type II 23% type III 13% were unsure Additionally, 50% had had a vaginal delivery; and 33% of these women reported that they tore into their urethra at delivery. Findings: A history of urinary tract infections (UTIs) was common in the cohort: 46% reported having at least one infection since being cut 26% in the last year 10% reported more than 3 UTIs in last year 27% voided ≥ 9 times per day (normal is up to 8 times per day) 60% had to wake up at least twice at night to urinate (once, at most, is normal) Most of the women (73%) reported at least one bothersome urinary symptom, although many were positive for multiple symptoms: urinary hesitancy (40%) strained urine flow (30%) intermittent urine stream (a stream that starts and stops and starts again) (47%) were often reported 53% reported urgency urinary incontinence (leakage of urine when they have a strong urge to go to the bathroom) 43% reported stress urinary incontinence (leakage of urine with coughing, sneezing, laughing or jumping) 63%reported that their urinary symptoms have “moderate” or “quite a bit” of impact on their activities, relationships or feelings What’s the Connection Between FGM/C and Urinary Symptoms? Urinary symptoms like the ones described above can be the result of a number of factors. Risk factors for urinary urgency and frequency, incontinence, and strained urine flow include pregnancy and childbirth, severe perineal tears in labor, obesity, diabetes, smoking, genital prolapse and menopause. However, given the average age of women in our sample and the fact that only half of them had ever had a vaginal birth, the rate of bothersome urinary symptoms are significantly higher than has been previously reported. FGM/C may be a separate risk factor for these symptoms. Interestingly, the prevalence of urinary tract symptoms in our patients closely resembled that of a cohort of healthy young Nigerian women aged 18-30, in which the researchers reported a prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms of 55% with 15% reporting urinary incontinence and 14% reporting voiding symptoms. The authors do not mention the presence of FGM/C in their study population but the published prevalence of FGM/C in Nigeria is 41%, with some communities reporting rates of 76%. Therefore, it is likely that many of the survey respondents had experienced FGM/C, thereby increasing the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in their cohort. In the study of women in Egypt referenced above, those with FGM/C were two to four times more likely to report urinary symptoms compared to women without FGM/C. The connection between FGM/C and urinary symptoms can be understood from the literature on childhood sexual assault and urinary symptoms. Most women who experience FGM/C recall fear, pain, and helplessness. Like sexual assault, FGM/C is known to cause post-traumatic stress disorder, somatization, depression, and anxiety. These psychological effects manifest as somatic symptoms. In studies of children not exposed to sexual abuse, the rates of urinary symptoms range from 2-9%. In comparison, children who have experienced sexual assault have a 13-18% prevalence of enuresis (bedwetting) and 38% prevalence of dysuria (pain with urination). The traumatic imprinting acquired in childhood persists into adult years. In a study of adult women with overactive bladder, 30% had experienced childhood trauma, compared to 6% of controls without an overactive bladder. There is a neurobiological basis for this imprinting. Studies in animal models show that stress and anxiety at a young age has a direct chemical effect on the voiding reflex and can cause an increase in pain receptors in the bladder. Additionally, the impact of sexual trauma on pelvic floor musculature has been well described. Women who

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 4: Psycho-sexual functioning

(This article is Part 4 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA When discussing psychosexual functioning following FGC, it is critical to acknowledge and recognize that many women who have undergone FGC will not experience sexual health problems. It is also important to note that many women with intact genitals do experience sexual difficulties. Female sexuality is a complex integration of biological, physiological, psychological, sociocultural and interpersonal factors that contribute to a combined experience of physical, emotional and relational satisfaction. Nevertheless, symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can interfere across the continuum of sexual behavior affecting desire, arousal, physical and/or psychological pleasure. The amygdala is the organ in the brain that alerts us to possible danger and responds to the danger by triggering the fear response along with the release of the stress hormones. A state of negative hyperarousal persists for those who have been re-triggered by some person, place or memory associated to the original trauma while suffering from PTSD (see The Body and The Brain). For some women affected by Female Genital Cutting (FGC), re-traumatizing triggers can be their initial (and ongoing) sexual experiences. Not only can the physical position (identical to that required for FGC) induce a flashback, but the already traumatized genital area can feel repeatedly violated with sexual activity, gynecological exams—or childbirth itself. [Note. in Sahiyo’s Exploratory Student on FGC in the Bohra community, 108 women reported that their FGC (khatna) had adversely affected their sex life – See Graph below] When these flashbacks occur the brain’s fear circuitry takes over and the hippocampus can no longer communicate effectively with the amygdala to allay its fears. This condition often leaves those affected feeling emotionally charged with generalized fear(s) that persist even after the traumatic event has passed. (See also ‘The Clitoral Hood – A Contested Site’) There are 3 primary psycho-sexual complications commonly associated with FGC: painful intercourse (may be due to narrowing of vaginal canal; or excessive scarring, or clitoral neuromas, or infibulation or chronic infection); difficulties reaching orgasm; and, absence or reduction of sexual desire. Sexual difficulties can occur because for FGC survivors, positive sexual arousal mimics the physiological experience of fear. Once these hormonal and neuroanatomical associations have been forged through the intense experience of trauma and the associated PTSD symptoms, it can be difficult to uncouple them. In these instances, arousal frequently signals impending threat rather than pleasure. Thus, the biology of PTSD primes an individual to associate arousal with trauma and this impairs the ability to contain the fear response—which in turn impedes sexual functioning and intimacy. Due to repeated pain during sexual activity, women may develop anxiety responses to sex that restrict arousal and increase frustration—all of which can contribute to vaginal dryness, muscular spasm, painful intercourse and/or orgasmic failure. Women may actively avoid sexual activity to minimize feelings of physical arousal or vulnerability that could trigger flashbacks or intrusive memories. Others have reported that merely the fear of potential pain during intercourse and the frustration around delayed sexual arousal contributes to the lack of sexual desire. Recurring pain triggers memories adversely affected by the cutting. Chronic pain and distasteful memories reinforce each other and create a situation of mutual maintenance. Emotional and/or physical pain during intercourse diminishes the enjoyment of both the woman and her partner. Complications such as these can contribute to feelings of worthlessness, inhibit social functioning and increase isolation. In fact, many women have expressed feelings of shame over being different and ‘less than’. Some may experience their circumcised genitals, now deemed ‘different’, as shaming. Others may feel responsible for the relationship distress that results and carry a burden of guilt for being unavailable to “provide” sex. They may perceive their anxiety and difficulty about permitting penetration as something they must overcome. The psychological issues for younger women who have undergone FGC and are living in Westernized societies may be especially complex. These women (and their partners) are subjected to different discourses of sexuality that centralize erotic pleasure and frame orgasm as the endpoint of sex for women and men. Some women may struggle with what are deemed irretrievable losses. Feelings of aversion may extend beyond sex to physical closeness or even intimate relationships in general. In other situations, a woman may feel inferior to other women or less entitled to positive relationships, so that she may engage in an unsatisfactory or even damaging relationship which could further diminish her self-esteem. Another underlying belief behind FGC is that women’s genitals are impure, dirty or ugly if uncut. As a result of this perception, the female body is viewed as flawed—forcing women to modify their physical appearance to fit standards far removed from health, well-being and gender-equality objectives. Unfortunately, the very nature of this subject often doesn’t allow for much insight, since FGC has always been shrouded in secrecy. Women may be reluctant to disclose because of the fear of being judged, since FGM/C is perceived by outsiders to be illegal, and abnormal. The belief that sexual matters are to be kept private also makes FGC-affected women inclined to keep quiet about their symptoms and suffer in silence or attribute their pain to other sources. However, healing from the trauma through talk therapy as well as open discussions about strategies for obtaining sexual pleasure after FGC can be critical for women to regain control of their sexual identity. For more information about the Psychosexual Consequences affecting the Clitoris see Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 5: The “C” Word…and I Don’t Mean Circumcision. About Joanna Vergoth: Joanna is a psychotherapist in private practice specializing in trauma. Throughout the past 15 years she has become a committed activist in the cause of FGC, first as Coordinator of the Midwest Network on Female Genital Cutting, and most recently

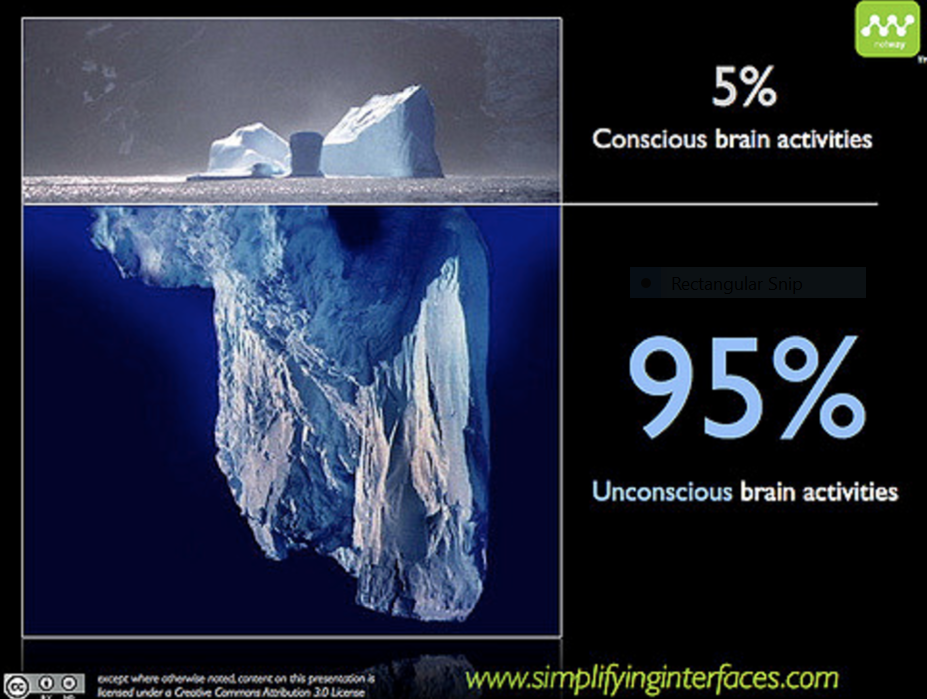

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 3: The Body and the Brain

(This article is Part 3 of a seven-part series on trauma related to Female Genital Cutting. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Trauma overwhelms us and disrupts our normal functioning, impacting both the brain and body, both of which interact with one another to regulate our biological states of arousal. When traumatized, we lose access to our social communication skills and displace our ability to relate/connect/interact with three basic defensive reactions: namely, we react by fighting, fleeing, or freezing (this numbing response happens when death feels imminent or escape seems impossible). In order to understand and appreciate our survival responses, it’s important to have a basic understanding of how our brain functions during a traumatic experience, such as undergoing Female Genital Cutting or FGC. Our brains are structured into three main parts: The human brain, which focused on survival in its primitive stages, has evolved over the millennia to develop three main parts, which all continue to function today. The earliest brain to develop was the reptilian brain, responsible for survival instincts. This was followed by the mammalian brain (Limbic system), with instincts for feelings and memory. The Cortex, the thinking part of our brain, was the final addition. The Reptilian brain: The reptilian brain, which includes the brain stem, is concerned with physical survival and maintenance of the body. It controls our movement and automatic functions, breathing, heart rate, circulation, hunger, reproduction and social dominance— “Will it eat me or can I eat it?” In addition to real threats, stress can also result from the fact that this ancient brain cannot differentiate between reality and imagination. Reactions of the reptilian brain are largely unconscious, automatic, and highly resistant to change. Can you remember waking up from a nightmare, sweating and fearful—this is an example of the body reacting to an imagined threat as if it were a real one. The Limbic System: Also referred to as the mammalian brain, this is the second brain that evolved and is the center for emotional responsiveness, memory formation and integration, and the mechanisms to keep ourselves safe (flight, fight or freeze). It is also involved with controlling hormones and temperature. Like the reptilian brain, it operates primarily on a subconscious level and without a sense of time. The basic structures of Limbic system include: thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus The Neocortex: The neocortex is that part of the cerebral cortex that is the modern, most newly (“neo”) evolved part. It enables executive decision-making, thinking, planning, speech and writing and is responsible for voluntary movement. But… Almost all of the brain’s work activity is conducted at the unconscious level, completely without our knowledge. While we like to think that we are thinking, functioning people, making logical choices, in fact our neocortex is only responsible for 5-15 % of our choices. When the processing is done and there is a decision to make or a physical act to perform, that very small job is executed by the conscious mind. How the brain responds to Trauma The fight or flight response system — also known as the acute stress response — is an automatic reaction to something frightening, either physically or mentally. This response is facilitated by the two branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) which work in harmony with each other, connecting the brain with various organs and muscle groups, in order to coordinate the response. Following the perception of threat, received from the thalamus, the amygdala immediately responds to the signal of danger and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated by the release of stress hormones that prepare the body to fight or escape. It is the SNS which tells the heart to beat faster, the muscles to tense, the eyes to dilate and the mucous membranes to dry up—all so you can fight harder, run faster, see better and breathe easier under stressful circumstances. As we prepare to fight for our lives, depending on our nature and the situation we are in, we may have an overwhelming need to “get out of here” or become very angry and aggressive (See ‘I underwent female genital cutting in a hospital in Rajasthan’ on Sahiyo’s blog). Usually, the effects of these hormones wear off only minutes after the threat is withdrawn or successfully dealt with. However, when we’re terrified and feel like there is no chance for our survival or escape, the “freeze” response, activated via the parasympathetic nervous system, can occur. The same hormones or naturally occurring pain killers that the body produces to help it relax (endorphins are the ‘feel good’ hormones) are also released into the bloodstream, in enormous amounts, when the freeze response is triggered. This can happen to people in car accidents, to sexual assault survivors and to people who are robbed at gunpoint. Sometimes these individuals pass out, or mentally remove themselves from their bodies and don’t feel the pain of the attack, and sometimes have no conscious or explicit memory of the incident afterwards. Many survivors of female genital cutting have reported fainting after being cut. Other survivors have reported blocking out their experiences of being cut (See ‘I don’t remember my khatna. But it feels like a violation’). Our bodies can also hold on to these past traumas which may be reflected not only in our body language and posture but can be the source of vague somatic complaints (headaches, back pain, abdominal discomfort, etc.) that have no organic source. FGC survivors who were cut at very young ages can be plagued with ambiguous symptoms such as these. Neuroscientists have identified two different types of memory: explicit and implicit. The hippocampus, the seat of explicit memory, is not developed until 18 months. However, the implicit memory system, involving limbic processes, is available from birth. Many of our emotional memories are laid