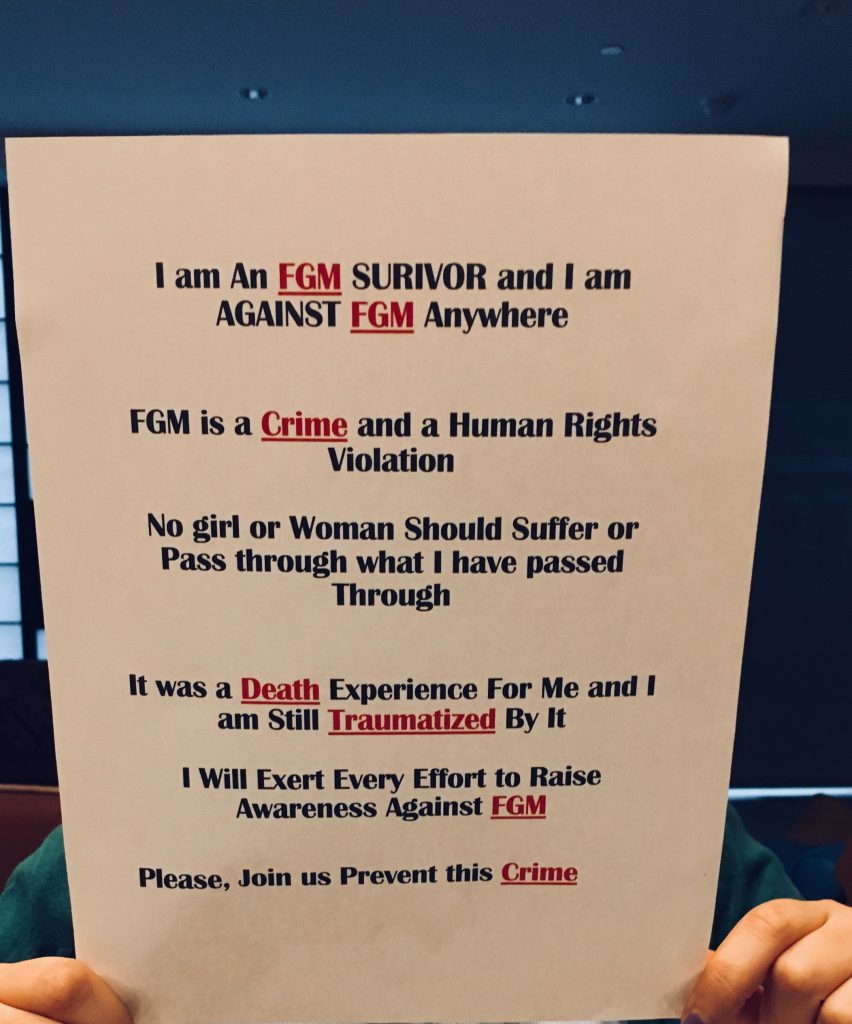

I Said It Loudly: I am an FGM Survivor. Meeting FGM Survivors for the First Time Was My Cursed Blessing

(Note: The following blog was written by a survivor who attended a meeting, the topic of which was on mental health and FGC. Her story highlights the power of storytelling and how it helps break the isolation that many survivors experience in having undergone FGC and dealing with their trauma afterwards, an isolation that Sahiyo is attempting to break via the storytelling work we engage in with communities.) By Anonymous Country: Egypt & United States Even now, despite my brain trying to convince me it was a good idea to attend a conference on FGM and Mental Health, I cannot emotionally explain what really happened that day. The conference consisted of FGM survivors, human rights advocates, therapists, and policymakers, and almost two weeks after having attended, I started to have stronger flashbacks of the terrible experience I underwent with FGM in my home country, Egypt. I have mixed feelings of love, support, and pain for having attended that conference. My journey dealing with that horrible experience started in my home country where my rights as a human being were violated without my consent. I was bleeding and almost died having been operated upon twice. Even now, I cannot easily write these words. You may wish to read my full story published here. The experience of meeting with other survivors from India and other countries was something I strongly needed to help bring me face to face with the many answers to the many questions in my mind regarding why I experienced so much anxiety, sadness, depression, panic, and fear after my cutting. I wanted to know how other survivors had dealt with their FGM especially those who spoke up about it publicly, such as (Mariya Taher, Leyla Hussien, Jaha Dukureh , Naima Abdulhadi, and others) ; I am relatively new to openly talking about it and I still feel as if I am climbing a mountain when trying to share or speak about it. I heard these women saying how it was and is still difficult; and listening to them has helped me to feel that I am not alone in my experience. I saw how powerful the pain of this experience can be, but at the same time was inspired by the courage of what they and I were determined to do. To speak up about FGM openly and to try to prevent it from happening to other girls. That meeting was the first time I met with and spoke to other survivors from different countries, such as the United Kingdom, Gambia, India, not to mention the United States. At the time, I felt happy that this meeting could serve as a comfort zone for me, knowing others understood what I had gone through. Seeing all those women in that room encouraged me to say amongst the group of almost forty members that I too am a FGM SURVIVOR. I knew these women would not shame me and I did not need to fear being labeled, judged, or threatened for publicly admitting I was a survivor. My heart was beating and my breath was short as if I had climbed a mountain. I thought I was ok during the 8-hour meeting, yet I collapsed and burst into tears at the end; I cannot precisely tell you why, but I thought about how it is unfair that our bodies and souls are violated with this harmful crime. Most of the time I feel sad that I had to go through these painful thoughts, feelings, or flashback of the operation room and after. It feels like I am being retraumatized when something happens to trigger the original trauma of FGM. I beg every mom and dad to see their daughters as beautiful souls who do not need to be cut to be pure. I am Muslim, and I can say it strongly, clearly, and angrily: Do not make it religious because it is not. My body was not supposed to be violated in this severe way nor was my soul. Yet, both happened. But I am comforted in knowing that there are others who I can talk to who understand my pain. FGM is a crime and more work needs to be done with healthcare professionals, as well as policy makers. Girls must be protected from being cut and survivors should be supported with the needed assistance to help them heal.

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 2: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

(This article is Part 2 of a seven-part series on trauma related to FGC. To read the complete series, click here. These articles should NOT be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed.) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Post-Traumatic Stress is the name given to a set of symptoms that persist following a traumatic incident and may be especially severe or long when the stressor has been of human design, such as in a violent personal/sexual assault (as in rape, torture, or Female Genital Cutting). These symptoms, which recreate the physical reliving of the trauma, can affect the way we think, feel and behave and, if experienced frequently, the condition that develops is called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a complex psycho-biological condition that develops differently from person to person because everyone’s nervous system and tolerance for stress is a little different. While you’re most likely to develop symptoms in the hours or days following a traumatic event, it can sometimes take weeks, months, or even years before they appear. The specific symptoms of PTSD can vary widely between individuals, but generally fall into the categories described below . Re-experiencing Re-experiencing is the most typical symptom of PTSD and occurs when a person involuntarily and vividly re-lives the traumatic event in the form of a flashback. Flashbacks appear as memories or fragments of memories from recent or past events and can leave you feeling fearful, confused and distressed. Jarring and disruptive, they can last a few brief seconds or involve extensive memory recall. Below are the categories and some examples of flashbacks: Visual Memories: various related images Auditory Memories: sounds of breathing, doors shutting, footsteps. Emotional Memories: feelings of distress, hopelessness, rage, terror or a complete lack of feelings (numbness). Body Memories: physical sensations like genital pain, nausea, gagging sensation, difficulty swallowing, feeling of being held down. Sensory Memories: of certain odors (e.g. perfume, body odor, alcohol) or tastes (e.g. sweat, blood). For some women affected by Female Genital Cutting (FGC), re-traumatizing triggers can be their initial (and ongoing) sexual experiences. Not only can the physical position (identical to that required for FGC) induce a flashback, but the already traumatized genital area can feel repeatedly violated with sexual activity, gynaecological exams or childbirth itself. Flashbacks can be accompanied by the same physiological reactions experienced at the time of the trauma, such as dizziness, rapid heartbeat, or sweating. In response to these distressing memories people can develop breathing difficulties, experience disorientation, muscle tension, pounding heart, shaking. Hyperarousal Trauma is stress run amuck. It dis-regulates our nervous systems and distorts our social awareness—displacing social engagement with defensive reactions. This state of mind is known as hyperarousal and often leads to: Irritability; angry outbursts sleeping problems; nightmares difficulty concentrating In severe cases, many have trouble working or socializing and may engage in reckless behaviors (driving too fast; being argumentative or provocative). Others with PTSD may feel chronically anxious and find it difficult to relax or concentrate. Also, problematic for many is difficulty falling or staying asleep or suffering from nightmares; feeling always anxious and on edge (referred to as hypervigilant) –they may easily be startled. Feeling afraid is a common symptom of PTSD and having intense fear that comes on suddenly could mean you are having a panic attack. It can happen when something reminds you of your trauma, and may trigger fearing for your life or losing control. Although anxiety is often accompanied by physical symptoms, such as a racing heart or knots in your stomach, what differentiates a panic attack from other anxiety symptoms is the intensity and duration of the symptoms. Panic attacks typically reach their peak level of intensity in 10 minutes or less and then begin to subside. Negative emotional states Some FGC-affected women may feel betrayed and develop problematic relationships with their mother, or female authority figures, and suffer from low self-esteem and concerns about body image. In addition, traumatized girls and women may develop persistent negative emotional states (e.g. fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame) and engage in distorted thinking such as “I am bad,” “No one can be trusted,” “The world is completely dangerous place.” In Sahiyo’s online survey of Dawoodi Bohra women, conducted in 2015-16, 48% of the women who had undergone FGC reported that the experience of FGC (khatna) left an emotional impact on their adult life. This impact included feelings of being haunted/traumatized by the memory of being cut, feeling betrayed and violated by the family, feelings of distrust towards them, as well as anger and fear. Avoidance and emotional numbing Trying to avoid being reminded of the traumatic event is another key symptom of PTSD. Individuals may try to block out the anxiety or fear associated with the distressing emotional feelings, by avoiding places, people and situations reminding them of the original traumatic experience. For example, the possibility of seeing the “cutter” in a social gathering may be very distressing and re trigger re-traumatization. (See A Pinch of Skin documentary by Priya Goswami). Some people attempt to deal with their feelings by trying not to feel anything at all. This is known as emotional numbing. Many people with PTSD try to push memories of the event out of their mind, often distracting themselves with work or hobbies. Others may engage in self-destructive behaviors (drug or alcohol abuse; eating disorders) in order to distract or numb themselves to feelings that are too painful to tolerate. Those feeling detached and numb often have trouble showing or accepting affection and, becoming isolated and withdrawn, may lose interest in people or activities they used to enjoy. Dissociation is a mental process that causes a lack of connection in a person’s thoughts, memory and sense of identity. It is a normal reaction to trauma and can help cut off the pain, horror and terror for a person experiencing mortal danger; an attempt to be “outside” the events (outside of oneself; besides oneself) happening rather than “inside”

એક સુલેમાનિ બોહરા પૂછે છે કે શું ‘સારા હોવા’ અને ‘ખરાબ હોવા’ ની વચ્ચે ફક્ત એક નાનકડો માંસનો ટુકડો

આ આર્ટિકલ પહેલા સહિયો દ્વારા તારીખ 09 માર્ચ 2017ના રોજ અંગ્રેજીમાં પ્રકાશિત કરવામાં આવ્યો હતો. (Read the English version here.) લેખક :શબનમ મુકબિલ ઉંમર : 52દેશ : ભારત આવું મારી સાથે પણ બન્યુ હતુ……. જ્યારે હું 6 વર્ષની હતી ત્યારે બે મહિનાનું ઉનાળાના લાંબા વેકેશનમાં હું મારી માં સાથે મુંબઈની સુલેમાનિ સમાજની એક સીટ, બદર બાગ આવી હતી, જ્યાં મારો જન્મ થયો હતો. સમાજના પરિસરમાં અમારૂં એક સુંદર નાનું કૉટેજ હતું જ્યાં મારી માંએ તેણીનું બાળપણ ગુજાર્યું હતુ. આજે પણ મને તે ઘર વિષેની નાની-નાની દરેક બાબતો યાદ છે જેમ કે, ફર્નિચર અને રૂમમાં તેની ગોઠવણ, રૂમ કેવા હતા, બહારનો સ્વચ્છ નાનકડો બગીચો, નાના બચ્ચાઓ જે મારી સાથે રમવા આવતા હતા, જે સહિયો બની ગઈ અને આજે પણ છે. વ્યક્તિની છ વર્ષની ઉંમરની યાદો ભૂંસી શકાય નહિં તેવી હોય શકે છે અને તેથી, આવી ખુશીની યાદો ના સાથે-સાથે એક દુખદ ઘટના પણ મને યાદ છે… મને યાદ છે કે હું દિવાલની સામે પહોળા પગ કરી બેઠી હતી અને એક વૃદ્ધ બૈરી ચાકુ લઈને આવતી હતી અને ત્યારબાદ એ અસહ્ય પીડા….. મને બરાબર યાદ નથી પરંતુ સંભવતઃ હું ખૂબ જ રડી હતી. મને એ પણ યાદ નથી કે હું કેવી રીતે ત્યાંથી બહાર આવી– સંભવતઃ લંગડાતા ચાલીને નીકળી, એમ કહેવું વધારે યોગ્ય રહેશે. પરંતુ, જ્યારે પણ મારે ટોઈલેટમાં જવું પડતું ત્યારે થતી પીડા, બળતરા અને લોહીવાળા અન્ડરવેઅર આજે પણ મને બરાબર યાદ છે. મને યાદ છે કે ખૂબ જ પીડા થતી હોવાના કારણે હું ટોઈલેટમાં જવાનું ટાળતી હતી. મને યાદ છે કે હું દોડી અને રમી શક્તી નહોતી, જે મને ખૂબ જ ગમતું હતુ. અંતે, હું સાજી થઈ ગઈ. વર્ષો વિતી ગયા. હું આ આર્ટિકલ લખી રહી છું તે એ દર્શાવે છે કે હું આ સંકટ માંથી બહાર નીકળી ગઈ છું. શું તેના કારણે મને કોઈ સેક્સ સંબંધી સમસ્યાઓ આવી? મને નથી લાગતું. ખરું કહું તો, સંજોગ વસાત મેં જ્યારે તે વિષે વાંચ્યુ ત્યાં સુધી મને એવું લાગ્યુ પણ નહિં કે હું એફ.જી.સી.નો શિકાર બની છું અને તે જુની અણગમતી અને પીડાદાયક યાદો તાજી થઈ ગઈ અને ત્યારે મને ખરી વાસ્તવિક્તા સમજાઈ. મને નથી લાગતુ કે મારા સંબંધમાં અથવા એક વ્યક્તિ તરીકે મારા પર તેની કોઈ વિપરીત અસર થઈ હોય પરંતુ, શા માટે 6 વર્ષની એક નાનકડી નિર્દોષ છોકરીને આવી ક્રુર પ્રક્રિયા હેઠળથી પસાર થવું જોઈએ? જેમ દાવો કરવામાં આવે છે તેમ, શું તેનાથી મને એક સારી મુસ્લિમ, શુદ્ધ અથવા પવિત્ર બનાવવાનો ઉદ્દેશ પ્રાપ્ત થયો છે? શું “સારા હોવા” અથવા “ખરાબ હોવા” વચ્ચે ફક્તએક નાનકડા માંસના ટુકડાનો જ તફાવત છે? હું કદાચ આઘાત મેહસુસ નથી કરી રહી પંરતુ, તે પીડાને હું ક્યારેય નહિં ભૂલી શકું. જે કંઈ થયું તેના માટે હું મારી માંને દોષ નથી આપતી કારણ કે તેણી પર સંબંધીઓનું અને સમાજનું દબાણ હોવાનું હું સમજી શકુ છું. આજે તેણી મારી સાથે આ પ્રથાનો પૂરા દિલથી તિરસ્કાર કરે છે, એવી પ્રથા જેના શારીરિક કે આધ્યાત્મિક એવા આરોગ્ય સંબંધી કોઈ ફાયદાઓ નથી પરંતુ, ફક્ત દુઃખદ પીડા આપે છે.

Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 1: What is trauma?

(This article is Part one of a seven-part series on trauma related to FGC. This article should not be used in lieu of seeking professional mental health and counseling services when needed) By Joanna Vergoth, LCSW, NCPsyA Many women who have undergone FGC may not have any lasting disturbances. But based on the Sahiyo study alone (see pie-chart below), there are those who may benefit from a deeper understanding of the effects of trauma. Often, we minimize, dismiss or normalize our symptoms and resign ourselves to feeling/living compromised. Learning more about trauma can provoke conversation; help one to feel less isolated and can prompt one to seek professional help. What is trauma? A traumatic event is defined as direct or indirect exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence. The incident may be something that threatens the person’s life or safety, or the life of someone close to the victim. Traumatic incidents can include kidnapping, serious accidents such as car or train wrecks, natural disasters such as floods or earthquakes, or violent attacks such as rape, sexual or physical abuse, or FGC. As defined—although culturally sanctioned— FGC is a traumatic event (see chart from Sahiyo’s study below). Although for some the consequences can be minimal, most of the evidence suggests that FGC is extremely traumatic and the physical or medical complications associated with FGC may remain acute or chronic. Early, life-threatening risks include hemorrhage, shock secondary to blood loss or pain, local infection and failure to heal, septicemia, tetanus, trauma to adjacent structures, and urinary retention. One of the more frequent longer-term medical consequences includes adhesions or scarring, which can contribute to lingering pain and impede sexual functioning. The focus of FGC has long been regarded from a physical and medical perspective but it is equally important to consider the psychological and emotional implications of this practice. It has been reported that the psychological trauma that women experience through FGM ‘often stays with them for the rest of their lives’ (Equality Now and City University London, 2014, p.8). Sahiyo’s study found that of the 309 participants in the study who had undergone FGC in the Dawoodi Bohra community, almost half (48%) reported that the practice left a negative emotional impact on their adult life. Usually, the girl, unprepared for what is about to happen, is taken by surprise and cannot prevent what is about to occur. Those that can remember the ‘day they were cut’ often report having initially felt intense fear, confusion, helplessness, pain, horror, terror, humiliation, and betrayal. Many have suffered a multi-phase trauma; the first being forced down and cut and then second is seeing or hearing another family member endure the procedure. Even anticipating the procedure, oneself can be terrifying. Also of significance is the community and family reaction to the painful reactions experienced by these young women. Often girls can be chided for crying and not being brave while undergoing the cutting. This dismissive, non-nurturing reaction can potentially lead to another facet of the multi-phase trauma. Some proponents of FGC actually consider that the shock and trauma of the surgery may contribute to the behavior described as calmer and docile—considered to be positive feminine traits. FGC is a traumatic event that can profoundly rupture an individual’s sense of self, safety, ability to trust and feel connected to others—aspects of life considered fundamental to well-being. Such genital violence can interrupt the process of developing positive self-esteem. And, when children are violated their boundaries are ruptured leading to feelings of powerlessness and loss of control. Children who have experienced trauma often have difficulty identifying, expressing and managing emotions, and may have limited language for describing their feelings and as a result, they may experience significant depression, anxiety or anger. Over time, if the distress can be communicated to people who care about the traumatized individual and these caretakers respond adequately, most people can recover from the traumatic event. But, some FGC affected girls and women experience severe distress for months or even years later. The symptoms of trauma: Outlined below are some of the consequences that may occur following a traumatic event. Sometimes these responses can be delayed, for months or even years after the event. Often, people do not even initially associate their symptoms with the precipitating trauma. Physical Eating disturbances (more or less than usual) Sleep disturbances (more or less than usual) Sexual dysfunction Low energy Chronic, unexplained pain Emotional/behavioral Depression, spontaneous crying, despair, and hopelessness Anxiety; feeling out of control Panic attacks Fearfulness Feelings of ineffectiveness, shame, despair, hopelessness Irritability, anger, and resentment Emotional numbness Withdrawal from normal routine and relationships Feeling frequently threatened Feeling damaged Self-destructive and impulsive behaviors Sexual problems Cognitive Memory lapses, especially about the trauma Difficulty making decisions Loss of previously sustained beliefs Decreased ability to concentrate Feeling distracted Over time, even without professional treatment, traumatic symptoms generally subside, and normal daily functioning gradually returns. However, even after time has passed, sometimes the symptoms don’t go away. Or they may appear to be gone, but surface again in another stressful situation. When a person’s daily life functioning or life choices continue to be affected, a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be the problem, requiring professional assistance. To learn more about PTSD, see our Part II – Post Traumatic Stress Disorder About the Author: Joanna Vergoth is a psychotherapist in private practice specializing in trauma. Throughout the past 15 years she has become a committed activist in the cause of FGC, first as Coordinator of the Midwest Network on Female Genital Cutting, and most recently with the creation of forma, a charity organization dedicated to providing comprehensive, culturally-sensitive clinical services to women affected by FGC, and also offering psychoeducational outreach, advocacy and awareness training to hospitals, social service agencies, universities and the community at large.

‘I feel dirty and violated’: A Bohra survivor of Female Genital Cutting shares her story

By Shaima Bohari Age: 21 Country: India I don’t remember how old I was. I remember just that I was a very young girl. My family and I were vacationing in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, in a small house not far from my maternal grandmother’s in Noorani Nagar. My mother called me, told me to change and said my grandmother was going to take me out for a little while. Me being the weird kid I was, I got excited. So we set out, my nani and I, on a little walk around the block. She explained to me that we were going to see an older lady who was going to help me with something that was for my own benefit. When we reached the house, my nani talked to this lady and introduced me to her. We went into a room in the back where three other older ladies were present. I was told to remove my pants and lie down on a mat laid out on the floor. I felt afraid and naked and my nani told me to just relax and held my hand. The women around me held down my arms and legs, keeping my legs apart. The lady of the house came in with something sharp in one hand and a cloth in the other, and she knelt down beside my legs. She used something like a glass to make a small cut and then pinched something near my vagina. I vividly remember screaming my lungs out and hitting and punching whoever was near my hands, flailing around like I was possessed. It was a short ordeal but it felt like hours had gone by since I’d left the house. I was told to get up and get dressed. As far as I can remember I wasn’t bandaged or covered with anything but the clothes that I came with. My nani gave me an envelope with some money and asked me to give it as salam to the lady who had mutilated me just minutes before. I was crying even as I kissed her hand and then left with my nani for the walk back, in my blood-stained clothes. After we came home, my mom laid me down on the bed on a set of sheets. Again I was naked from the waist down, and was told to stay there until the bleeding had stopped. I pushed that memory down and out, or at least I tried to. I could never really forget it though, and now I’m not sure I want to. It was a barbaric and horrible event that I had to go through, but I don’t want to repress it because clearly, that hasn’t worked until now. I suffer from a myriad problems because of that one incident in my life. I still don’t know how to deal with it. I suffer from pain in my vagina, I can’t look at myself naked, I have self-esteem and body issues because every time I look at myself I feel dirty and violated. I doubt I will ever be able to have a relationship with my future spouse if I decide to get married because I can’t imagine it. I suffer from severe depression which, at least partly, stems from this. To all the men who have the audacity to tell me that this barbaric mutilation of the female form is inconsequential and alright because it is a religious act: it’s easy for you to say this since you haven’t gone through the trauma. Also as we all know, this systematic, brainwashing and torturing of women is a weapon in your hands. To all the women who defend female genital mutilation, I want you to know that you are an insult and a curse to all the women who have suffered from the traumas of FGM, and it is YOU who make it okay for men to abuse us. You give them the power to mutilate and oppress us when you stand against other women. Although I cannot speak for any higher power out there, you will find no forgiveness from me. I also want to point out that although I do blame my grandmother, and my mother, and every member of my family who didn’t stop them, and those who let their own daughters, nieces, cousins, and granddaughters be mutilated, I understand that the majority of the blame lies with the institution that made them believe that this is righteous. Finally, I ask anyone who reads this to talk to any woman you know about this. Tell them they’re not alone, and that it doesn’t make them any less of a human for having gone through this. Talk to other people, raise awareness about this inhuman practice, so that it is no longer a taboo topic. So that women everywhere are able to open up about their horrific past and know it wasn’t their fault.

‘Far from enhancing my marital bliss, khatna had all but devastated it’

by: Anonymous Age: 30 Country: United States I first learned that khatna had been performed on me when I was 11 years old. My mother told me, and even then the hair on my neck rose and I had a clear instinct that what had happened wasn’t right. I asked my mother why Bohra girls were cut when there was no evidence that it had the same benefits as male circumcision. She responded with the familiar refrain: hygiene, marital bliss. At that time, I had no idea what a clitoris was supposed to look like. My mother described it to me, never using that word, but saying that it was a “long thread of flesh” that hung out of the vaginal hood. It had to be cut because it would otherwise rub constantly against my underwear. For the Potterheads out there, the image that sprang to my mind was of an Extendable Ear in my panties, a long flesh-colored string that had to be snipped to curb continuous arousal. I had never seen a picture of a clitoris, nor could I. I’d grown up in a country where the Internet was heavily censored and the chapter on reproduction was ripped out of our Biology textbooks. That image of the clitoris as a long flesh-colored string stayed with me until I looked at cartoon pornography as a teenager in the United States. But let me be clear, because this detail about my education is a gateway to Orientalism: I had an excellent primary education, and I was far better prepared for graduate school than many of my US-educated peers. The fact that schools in that region refused to include human reproduction in the curriculum was shortsighted and foolish, but not unlike the abstinence-only curriculum I’ve learned about since moving to the US. But let me return to that moment my mother told me I’d been cut: since it never crossed my mind that I would or could be sexually active before marriage, I only thought about khatna once or twice a year until I was married. And that’s when I realized that sexual intercourse was extraordinarily difficult for me. My vagina would convulse, and even the thought of using a tampon triggered these convulsions. My condition went undiagnosed until years later when my OB/GYN attempted to do a pelvic exam. She had no warning because I did not tell her about my difficulty with intercourse. Peering over the stirrups, she apologized for causing me pain, and asked me to breathe deeply while apologizing rapidly: “Just one finger, I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m so sorry almost done almost done, and relax.” I learned that I had vaginismus, and needed physical therapy. As I talked through my condition with my wonderful doctor, I learned that an early childhood trauma was likely the cause for my vaginismus. The symptoms pointed towards a psychological trigger rather than physical limitations, and the more I reflected on my condition the clearer it became that I had always been unable to tolerate even the idea of penetration from around the age khatna had happened to me. Any kind of insertion seemed laughable to me as a teenager, whether I was washing myself in the shower or attempting to masturbate. This points to the idea that women who don’t consider themselves victims – and I certainly didn’t and don’t – can experience long-term effects of khatna that we may not even (or ever) be aware of. When I eventually saw a picture of a healthy and anatomically accurate clitoris for the first time, what I’d already suspected was confirmed: there was no hygiene-related reason to snip it, and far from enhancing my “marital bliss” it had all but devastated it. But learning about khatna revealed something about me to myself: even as a child, I recognized the value of empirical research when it came to making decisions about altering bodies – particularly female bodies, which have historically always been more vulnerable. Even as an 11-year-old, I knew the benefits of male circumcision – I had just learned about trench warfare during World War II, and the infections that raged among uncircumcised men living in those filthy conditions. And as I reflect on that moment when I was 11, it makes perfect sense to me that I chose a career in research. Another thing I recognized is that not only is the term “victim” disempowering when referring to women who have experienced khatna, but also entirely inaccurate. Activists have argued against the term “victim” for decades, particularly when it comes to describing women and gender-queer survivors of physical abuse. However, the term is misleading too. It is an easy label assigned by the status quo, and a particularly effective way for those in power to demonstrate their investment in “women’s issues.” It is a gateway to continued imperialism, where the narratives of marginalized groups are stripped of nuance, or hidden entirely. It has been incredibly easy, even comforting, to vilify Dr. Jumana Nagarwala for performing khatna in the US. But let us not buy into the clash-of-civilizations narrative. Each time a US news outlet says the practice will not be “tolerated in the US,” there is an implied comparison to those “backward” countries that tacitly endorse it. Additionally, it implies a wounded nationalism, where (White, male) individuals are almost more outraged that it is happening in the United States than that it is happening at all. And so we are forced to view the practice through an imperial lens. We must not let khatna become a political talking point for US politicians to show how they have “zero tolerance” for “brutal” practices while forwarding a facile concern for women’s rights. We must not forget that khatna is endorsed by the largely male leadership of the Bohra jamaat. While Dr. Nagarwala is culpable, and there is no question that she must face legal action, she has been turned into a scapegoat by both US discourse and the Dawoodi Bohra leadership.

I underwent Female Genital Cutting in a hospital in Rajasthan

(Trigger Warning: Below is the account of one woman’s experience with FGC. We thank her for being brave and sharing her story with us) By: Jamila Mandsour Age: 25Country of Residence: KuwaitCountry where Khatna took place: Banswara in Rajasthan, India That day, I was taken to the hospital to see my newborn cousin. Although the mom, my aunt, and her baby boy were already discharged, my mom told me they were still there. I was five and so very excited to see the baby. My excitement crashed when I was thrown into a dark room and a nurse put me on a stretcher. I screamed and was slapped on my face. My voice was silenced. After ten minutes, I came out of the room wounded and in tears. I had no idea what happened to me in those ten minutes because I fainted. I was partly aware that a knife had been held towards my genitals, but a five-year-old does not have the guts to ask the adults why she was thrown into a dark room. My brain did not have the ability to understand that my legs were spread to cut some skin from my clitoris. After coming out of the room, I was not aware of that injury and could not understand why I was bleeding. Since childhood, I have been an active person, always running from here to there. But on that day, after leaving the hospital, I was totally exhausted from the crying and yelling because of the pain that knife had caused me. I went home and slept, not waking until the evening. Upon awaking, I saw that blood on my mattress and finally, I asked my aunties (my mother’s sisters) why I bled. I don’t remember any of them answering me. They told me not to wear my underwear for the rest of the day. Even at that young age, I felt awkward about going without my underwear. I wanted to rise from my bed, to run around and do my daily somersaults, but I could not because of my injuries. For the next few days, I couldn’t even walk properly. That day left a mark on my memory forever. After a few days, I returned to my regular daily routine. Not thinking about that day until eight years had passed and my sister suffered through the same thing I did. I was thirteen then, and I can recall her sad face, filled with pain, asking me the question, “Why was I cut?” What could I say to her? I had no answer to give her and it broke my heart. For the second time in my life, I went through the same emotional pain and felt helpless, keeping mum on the subject. An invisible hand had slapped me once again with the reality of what I and my sister had undergone. Even now at this moment, while I write this story of mine, chills run down my spine. In my 20s, for the first time in my life, I really tried to find answers to my question of why we were cut. I got no answers. One thing I was sure about: it shouldn’t have happened to me in the manner that it did, even if the religious authorities had deemed it valid. Even today, not many want to talk about this hideous act, but every pain has a scream and on some days the pain reaches out and my scream is loud. In time I did get answers, but I still wonder why the community practices this ritual when there is nothing reasonable about it. Out of a hundred women, I think ninety-eight would either not know of any scientific or religious reason to perform it, or would say they do not want to discuss it with others. If some women are adamant about being silent and feel guilty about speaking about khatna, then I wonder why they make sure their kids undergo it? I don’t know how, to sum up this article. One thing I know is that khatna is painful, it is harsh, torturing, shattering, and heart-breaking. It affects the sexuality of women and causes emotional and mental suffering (this is true in my case). While writing this piece, I couldn’t control the tears flowing down my face, as it expressed my pain. I request all of you who read this story of mine, please stop practicing khatna. One piece of skin should not decide the character of your daughter. Please be sensible about what happens to your baby girl.

‘I want Bohras to wake up and stop practicing Khatna’

By: Anonymous Age: 32 Country of current residence: Bahrai I’m a victim of FGM and this is my story. It’s the same as every other FGM survivor. India. A dingy house. An old woman. A blade. Pain. Blood. Being given chocolate. And then being yelled at to stop crying. And the thing that hardly anyone talks about is how ANGRY it makes you and how you can’t find ways to release the anger. It’s been 25 years and I’m still so, SO angry. Why was a piece of me cut off for an unnecessary reason? Why was psychological trauma inflicted on me at such a young age? Why am I suffering from horrible period pain every month just because my mother blindly followed what was expected of her to do? Why do I have to feel the pain of seeing the guilt and shame on my mother’s face now whenever this topic is raised because she hates herself for what she did? And why is it STILL being done to little girls who don’t have the power to stop it? It makes me mad, mad, MAD! And this always makes me wonder how others follow this religious leader or even stay in this community. Why don’t more Bohras question the teachings? Why don’t they protest? Does the dream of heaven make them so blind that they approve of abuse on young girls? I’m so, SO happy to see FGM get media traction and be publicized for the world to see. I want to see FGM STOP. Let the leader declare that khatna needs to be stopped so the Bohras who follow his every command will stop mutilating their daughters. I want Bohras to realize they CAN decide for themselves what is right and wrong. Cutting off a part of girl children’s genitals without their consent, for no medical reason, is completely, and unequivocally wrong.

We must find culturally sensitive methods to end FGC and protect girls from further trauma

Picture an innocent, 7-year-old girl being led to an unfamiliar room. She is made to lie down, her underpants are removed, and a piece of her is cut away; familiar hands around her upholding an age-old tradition. Perhaps she is in pain. Perhaps she is not. She might feel betrayed, scared, angry, or upset. She might want to run away from the people who are albeit familiar to her, but who have put her in an extremely traumatic situation. Now picture this same girl once again, made to lie in a an equally unfamiliar room, her underpants removed, her private parts probed by a doctor, who is looking for the scar from the piece that was cut away from her; these concerned hands are trying to build a case to condemn the ones who caused her the original pain. The girl is once again in pain, but this time it may not be just a physical pain. She is again angry, scared, and confused. And this time, she probably wants to run back to those who are familiar to her, to save her from the trauma of reliving that memory. The above two scenarios sadly highlight the unfortunate situation that innocent Bohra girls in the US are reportedly in. The girls are possibly feeling trapped, fearful, and vulnerable, because once again they are being forced to relive their trauma of undergoing Khatna. Recently, Female Genital Cutting or Khatna prevalent in the Dawoodi Bohra community came onto the federal radar in the US because of the arrest of a doctor associated with the practice in Detroit, Michigan. This arrest was followed by a few more arrests leading to subsequent intervention by Michigan’s Child Protection Services who reportedly picked up children for further questioning. While we need law to make clear that FGC is a human rights violation, and we need legal aid to further efforts towards preventing FGC from occurring in the first place, subjecting a child to a double scrutiny of sorts may not be the best practice if we keep the interests of the child in mind. For instance, one has to understand that Bohra-style Khatna can be difficult to establish in a medical examination, because Type 1 or Type 4 (which Bohras typically perform) do not necessarily leave physical scars. The girl may have lost a thin layer of her prepuce, or she may have been pricked, slit or rubbed, in which case subjecting them to medical check-ups is not going to prove anything, and may, in fact, cause them trauma when previously they may not have been particularly traumatized. Additionally, carrying out a witch hunt on all the mothers, possibly separating the girls from their parents, and asking for a ‘permanent termination’ of rights to parenting, are all methods that might force the Dawoodi Bohra community into believing that they are being targeted unfairly, and these actions might make them distrustful of law enforcement officials. Moreover, the child might view the authorities trying to protect her as her worst enemy, because they separated her from her parents and everything that is comfortable and familiar to her. She might also feel pangs of guilt if her testimony leads to her mother’s arrest. After all, no child wants to be the reason for a family’s disruption. There is no doubt that the US government is doing exceptionally well in investigating the case, and ensuring that the laws of their land are rightfully upheld. Nevertheless, Sahiyo does feel that there are certain realities, which if understood and implemented correctly, could make the process of serving justice less painful for the child. For instance, what could be explored is how to gain insight around culturally appropriate and sensitive forms of outreach from the people and agencies who are knowledgeable in working with the community. Since its inception, Sahiyo’s philosophy has been to engage the members of the community and seek their help to end this harmful practice. So we ask now, could an alternate approach be found that acknowledges Khatna as a harmful tradition that must be discontinued, but simultaneously recognizes that parents’ intentions for continuing it are not necessarily malicious? Or, could there be a more educative, community-involved approach to tackling FGC which recognizes it as a social norm that unfortunately has been passed down through generations of a community? Could state-organized counseling sessions for the parents and children be an alternative to punitive punishments? We ask these questions because we acknowledge that to truly end FGC in the Dawoodi Bohra community, we must find methods that will not cause further trauma for the child, but at the same time, continue to move the community forward towards abandoning this undesirable and harmful practice.

Is there only a little piece of flesh between ‘good’ and ‘bad’, asks a Suleimani Bohra